The economic risk that dare not speak its name – what happens to us if China goes down?

News

News

Call it unenlightened self-interest, but there’s one China question – perhaps above all others – which Australian economists, captains of industry and CEOs have long needed to ask, but no-one’s quite had the stomach to game out.

The gods today stand friendly that we may,

Lovers in peace, lead on our days to age.

But since the affairs of men rests still incertain,

Let’s reason with the worst that may befall.– Cassius (Act V Scene I, Julius Caesar)

Fortunately, this week an all powerful cabal of Australian banking regulators – hardened by decades of dealing with the tricksiest of global bankers and Aussie economic hooligans – have finally broached the issue.

On Wednesday last week at an undisclosed location and almost certainly under cover of darkness, the little known Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) held its regular quarterly meeting to deliberate over a few evolving risks to the stability of global and domestic financial markets.

The CFR is ALL heavy-hitters. Made up of the Big 4 Bank Watchers – the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the Australian Treasury and the Reserve Bank.

Chaired by the Reserve Bank Governor Michele Bullock, “The Council” as they call themselves, meets as required to “promote (the) stability of the Australian financial system and support effective and efficient regulation.”

In doing so, the Council presents itself as a benign, non-statutory organisation, without any particular regulatory or policy decision-making powers… but who needs any of those powers, when they already reside collectively within its four members?

But cool conspiracy framework aside, there’s quite a few ‘evolving risks’ out there right now and last week The Council was updated by their own internal ‘Working Groups’ which report back with the latest on cyber risks and resilience, crisis management arrangements and climate change.

But of all the various risks The Council discussed, the glaring risk on our doorstep which has lacked serious consideration here in Australia for some time and remains very real, if not imminent, is:

Well, the CFR is seeing a deterioration in the shaky foundations of the world’s second largest economy, beset as it is by a world of problems orbiting an awful residential property catastrophe.

“There is increased uncertainty around the outlook for the Chinese economy due to stresses in the property sector interacting with longer-term financial vulnerabilities,” the council warns.

“A sharp slowdown in China, were it to materialise, would principally transmit to Australia through trade channels and through an increase in risk aversion in global financial markets.”

Oh no. An increase in risk aversion? Across global financial markets?

If that’s our principal worry, things must be alright. Frankly, global markets could use a little risk aversion.

But, like many in this newsroom, it’s just not that simple.

AMP Capital’s Diana Mousina says Australia is highly dependent on the Chinese economy because of demand for Australian mineral resources and agriculture.

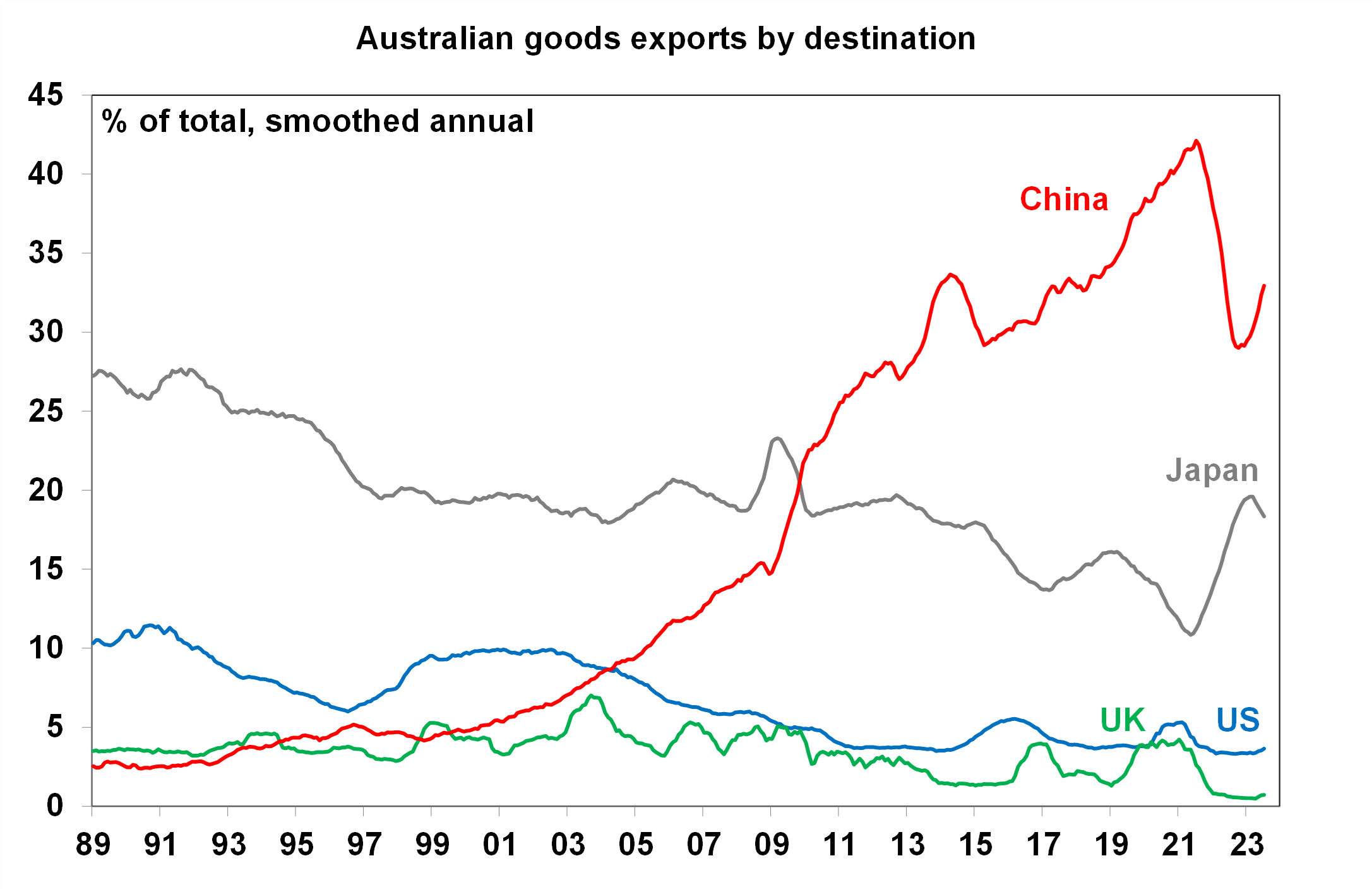

For example, Diana says goods exports into China were 42% of Australia’s total goods exports in 2021. Today China receives 33% of our total exported products. That is, for the mathematically inhibited, a third of everything we send OS goes to China.

But does this mean weakness in the Chinese economy will also weigh on Australian economic growth?

It’s been easy to ignore of late – what with pandemics and cold shoulders, tariffs and the like – but China is still Australia’s Number #1 bilateral trading partner.

But, (if memory serves) as the old saying goes: when China farts, Australia collapses in a great heap.

Across both goods and services, a full third of Australia’s global trade still ends up in the Middle Kingdom, as per the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).

In 2022, two-way trade clocked in at US$220.9bn, down 3.9% YoY, with Australia’s exports to China hitting US$142.09 billion, (down some 13% from 2021), via official numbers from China’s General Administration of Customs (GAC).

As of December 2022, the top exports from Australia to China included iron ore (US$5.48 billion), petroleum gas (US$1.65 billion), other minerals (US$1.08 billion), gold (US$742 million), and wheat (US$214 million).

And more recently, China has begun lapping up almost the entirety of Australia’s lithium output.

And in the first half of this year, Australia’s exports to China hit a record US$102.5 billion, as lithium concentrate jumped liquefied natural gas (LNG) as Australia’s second biggest export to China behind iron ore, with sales spiking to $11.7 billion between January and June. During the same period in 2021 by comparison, 1H sales of lithium to China were just $470 million.

This is a measure of China’s fabulous embrace and global dominance of both critical minerals processing and of the energy transition more generally.

According to the Department of Industry, Science and Resources, remove China from the lithium export equation and we have some 2% LiO2 heading to Belgium and 1% each to the United States and Korea.

According to David Uren, senior fellow at ASPI, China’s capture of Australia’s lithium exports highlights the tension between economic forces and strategic policy, with Five Eyes countries giving clear preference to building supply chains with Western partners that bypass China.

The Foreign Investment Review Board’s (FIRB) been busy doing its bit too. The FIRB rejected major investment attempts by Chinese companies to open up the Australian critical minerals industry.

The FIRB’s intervened in (Chinese-linked) Astroid Australia’s purchase 90% of lithium miner Alita Resources (ASX:A40) and prevented Yuxiao Fund from increasing its 9.9% stake in rare-earths miner Northern Minerals (ASX:NTU).

However, Uren says, China has been building its expertise in critical minerals since the 1980s.

“Its unrivalled lead in processing and manufacturing technology makes it the obvious choice for buyers wanting quality refined critical minerals.”

“More broadly, the concentration of export markets in China exposes Australia to the impacts of both downturns in the Chinese economy and future geopolitical tensions between the two countries.”

And then there’s the report a few weeks back from Rural Bank, showing China’s still by very far Australian agriculture’s biggest and best market. Despite the recent trade tensions and tariffs, agricultural exports to China jumped 20% to a stupendous new (record) high of $16.6bn – proving there’s been little incentive yet for the sector to go diversify away from its hungriest and most lucrative customer.

So. China remains the single primary export market for all sorts of ASX-originated products. The coal, iron ore, the metals, (and even the lobsters and wine).

Australia, unsurprisingly is merely China’s fifth largest source of imports and 10th largest export market.

In 2018, to show his old boss who’s boss, Australian PM Scott Morrison banned Chinese tech giants Huawei and ZTE from participating in its telecom infrastructure. Invoking national security concerns and lobbing as few poorly worded allegations at China, Australia revelled in becoming the first member of the Five Eyes intelligence alliance to prohibit Chinese tech. From there the government openly supported and often quipped about the swiftly ensuing US-led efforts to hobble and contain China’s expanding belligerent influence in the Indo-Pacific.

Classic hits like:

Then with Covid-19 a handy stick for the PM to whack China with, bilateral ties took a sudden dive.

China retaliated to the COVID-accusations by banning imports on heaps of Australian exports, including coal, barley, wine, cattle, and seafood.

Australia responded by escalating the trade dispute to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and nixed the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) deal previously agreed to between China and the state of Victoria.

Nevertheless, Mousina notes China’s been our top trading partner now for almost 14 years and remains so today.

The last five of those years, however, have accumulated all sorts of tensions on a range of issues related to security, technology, politics, and trade.

Diana says the consequent decline in exports to China reflects the trade tensions between Australia and China which in the last two years impacted around $23bn (or 4.5% of total exports) worth of goods (mostly agricultural and coal exports and some of which have now been reversed).

COVID-19 lockdown disruptions also reduced Chinese import demand, followed by the more recent softening in Chinese growth.

Despite the fall in exports to China since mid-2021 Australia’s trade surplus has averaged $11 billion over 2023, roughly double its value compared to pre-COVID levels.

Source: ABS, AMP

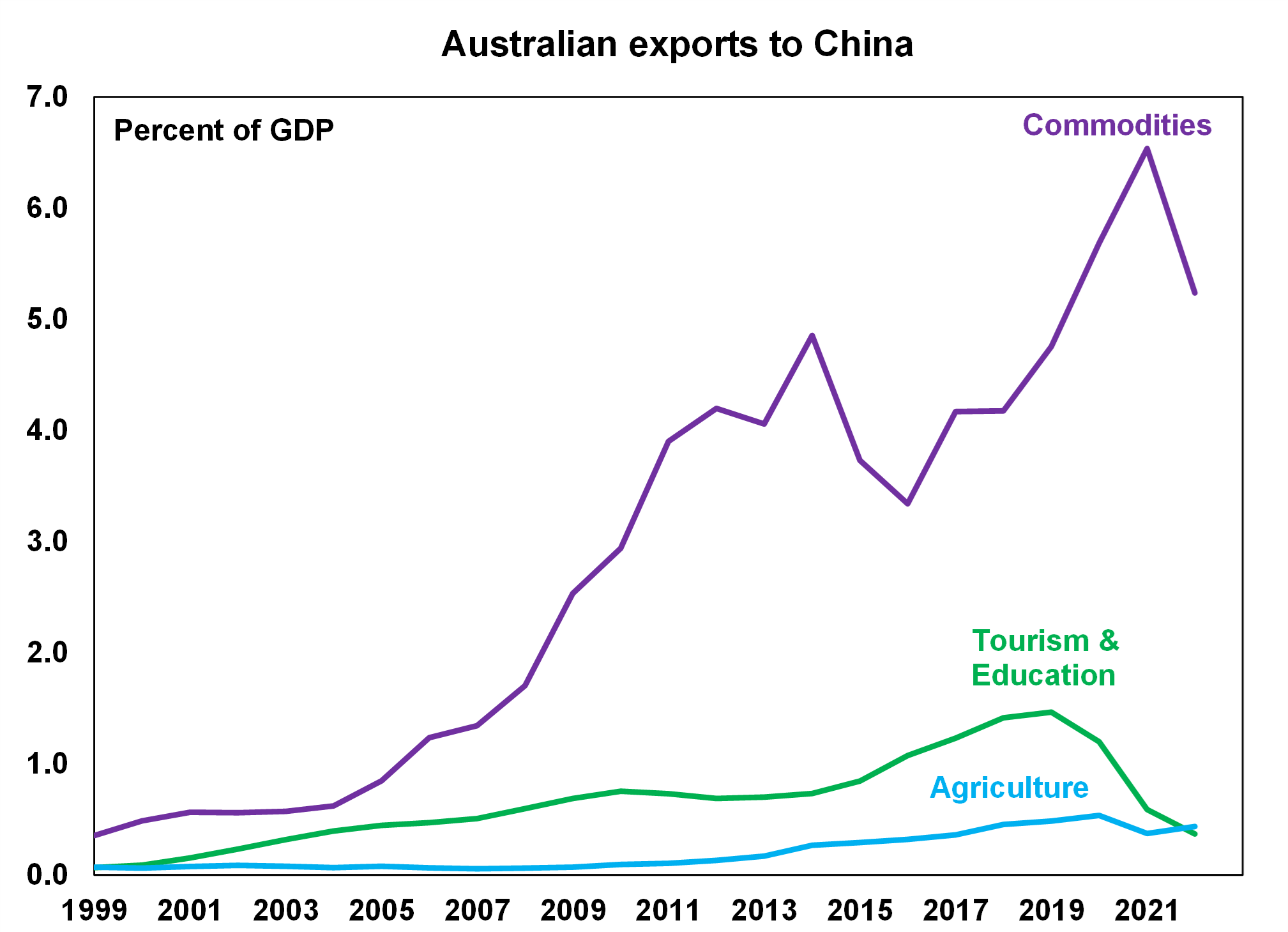

Commodity exports to China are the main link to the Chinese economy (see below) and are worth over 5% of GDP to Australia in nominal terms.

Source: ABS, AMP

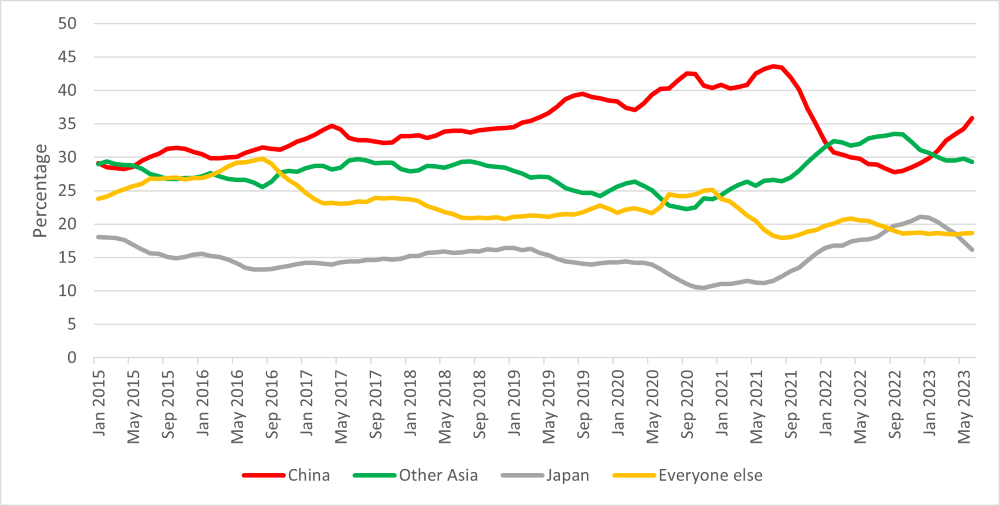

Diana says our top export commodities into China remain iron ore, which is Australia’s single largest export, at around 22% of total exports, coal and Liquified Natural Gas (LNG).

When it comes to iron ore, China loves the stuff and uses it to make steel for buildings, infrastructure and consumer products like electric vehicles.

Australian commodity exports have benefitted from strong economic growth in China in the decade prior to the pandemic. The volume of iron ore exports peaked at 10% of GDP in 2020 and have declined to 8.5% of GDP.

“But, iron ore prices have remained high which has boosted the trade balance and helped to offset the decline in export volumes,” Diana says. “China’s potential economic growth is expected to be soften over the next few years to 4% versus the 10% the world was used to in 2006-10 and growth in commodity-intensive sectors like construction and infrastructure will be under strain which is negative for iron ore demand.”

However, there may be some offset.

“China’s urbanisation rate has further to increase from its current level of 64%, as it is well below advanced economies which tend to be over 85%. Australia also has an advantage of being a high-quality producer of iron ore and is subject to less delays and strikes and closures compared to the other major iron ore producer, Brazil or even China’s own iron ore sector.”

Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have stepped up as our other major iron ore importers, and Diana says they may also be able to absorb some of the slack from lower Chinese demand.

“As well, China’s economy is much bigger than it was in 2006-10 when it was growing at 10%, so the pace of growth to generate the same level of commodities demand is equivalent to around 4% GDP growth now.”

“Revenue from commodity exports also have an important bearing on the Federal government’s budget revenue,” Mousina says.

“The strength in commodity prices over the past year lifted corporate tax revenue and the stronger labour market which boosted payrolls tax receipts which has been one of the reasons that Australia’s 2022-23 budget outcomes are running well above estimates and we ended up with a budget surplus of 0.9% of GDP in 2022 23.

“Conservative Treasury estimates of commodity prices, which are running above projections, also mean that there is upside risk to Federal budget projections. Better budget outcomes give the government room to lift spending (although the current high inflation period indicates that this would be unwise at the moment).”

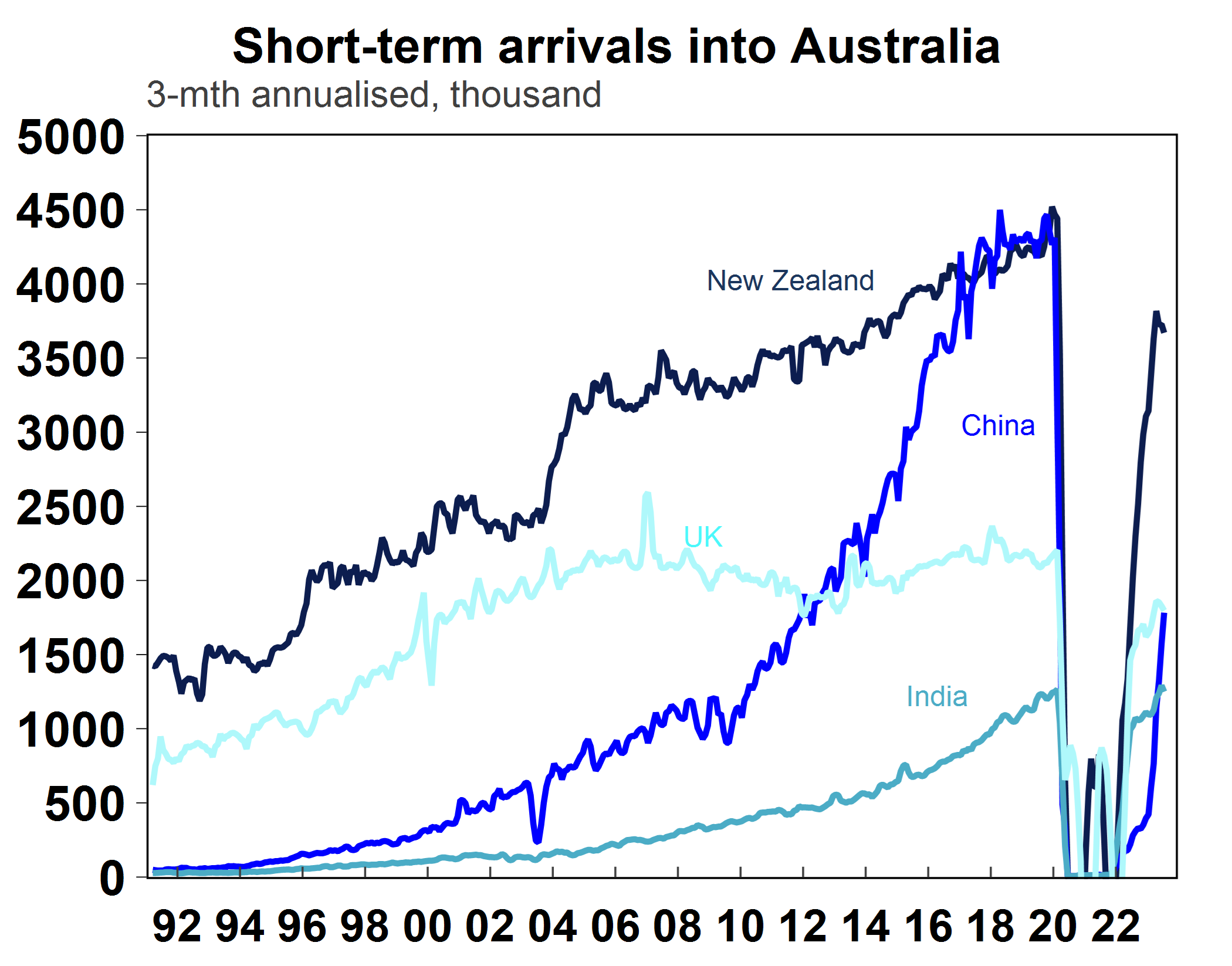

Before the pandemic, Chinese arrivals were the top source of short-term arrivals into Australia, alongside New Zealand.

“Short-term arrivals (those coming for less than a year) are still around 30% below their pre-COVID levels but Chinese arrivals are still less than half of their pre-pandemic levels, so have much further to go to get back to normal,” Mousina notes.

Source: Macrobond, AMP

Despite this shortfall, AMP Investment’s research shows the impact on tourism hasn’t been entirely disastrous; in fact employment in the tourism sector in areas like accommodation and food services, retail and arts and recreation has held up well over the past year.

“The lack of Chinese short-term arrivals has been offset by high holiday spending by Australians and a high level of permanent migration into Australia with current net overseas migration running around 500,000 or more – a record high.

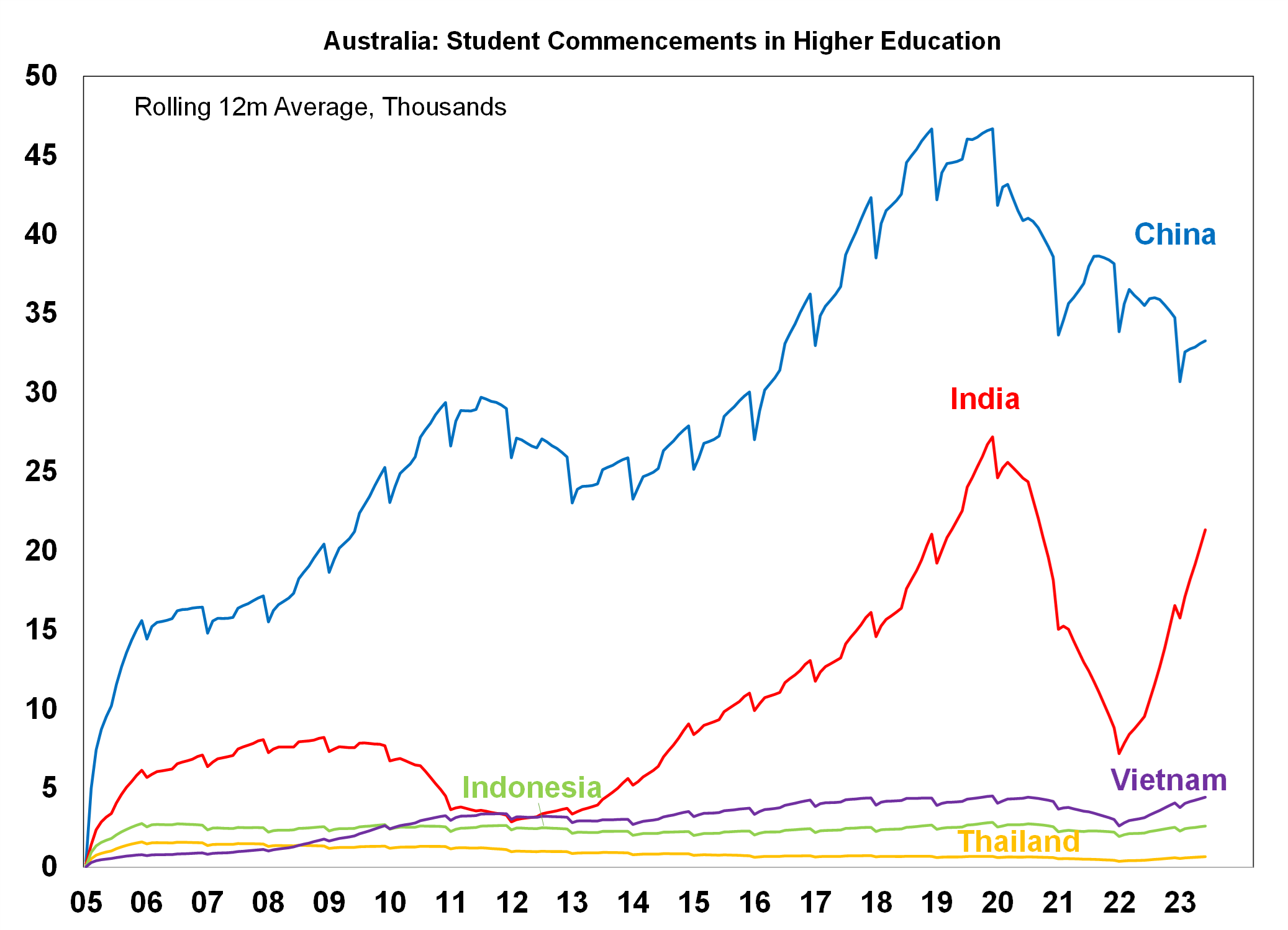

“Chinese students have been the major country group of education arrivals into Australia since 2005 (see below). The pandemic has led to some drop-off in Chinese students, but the impact has not been as large compared to tourism which has helped to support the higher education sector.”

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

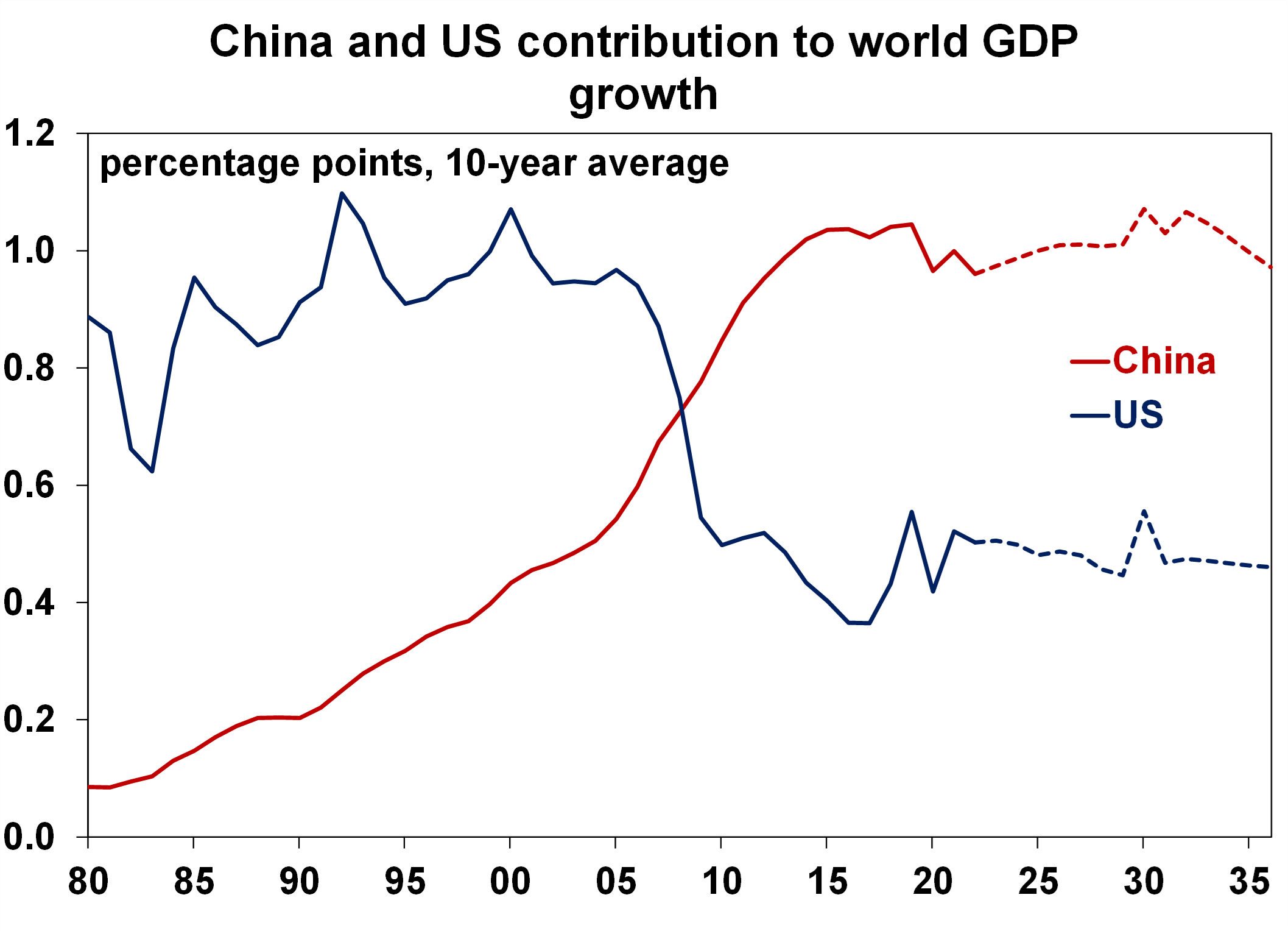

There are all sorts of long-term structural forces that will result in lower Chinese GDP growth over the next few years, Diana says.

There’s debate where that’s headed but she reckons Chinese GDP could loiter around 4% now and 3% next decade.

“This is compared to the 10% rate the world grew accustomed to in 2006-10 due to high debt levels in China, an oversupply of property, an aging population and slowing productivity growth… This means that China will make a lower contribution to world GDP relative to its recent outcomes and this will result in lower potential world economic growth.”

“The potential pace of global growth is around 3% or slightly above per annum but with lower contribution from China, this will slow to 2.5-2.7% per annum without another growth driver offsetting the decline from China.”

This means that simple, slowing demand from China will inevitably impact other countries, including Australia.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

“From a financial market point of view, the Australian dollar is sensitive to outcomes in the Chinese economy. The 5% depreciation in the currency since early 2023 partly reflects concern about the Chinese economy,” Diana says.

The impact on shares from softer Chinese growth has been mixed.

“Australian shares have been close to flat throughout 2023, underperforming global peers in the US and Europe, and reflect poorer earnings growth, an economy that is more sensitive to interest rate changes compared to most of our peers and some negative impact to resource companies from lower Chinese demand.

“The flexibility in Australia’s economy to manage to offset the weakness in Chinese economic growth indicates that Australia may not be as tied to Chinese economic growth as is commonly accepted.”

According to Uren at ASPI, the experience of the past two years shows there’s wriggle room yet for Australia, if China goes bottom up.

“The experience of the past two years, when the Australian economy barely noticed the impact of China’s trade strikes, underlines the flexibility and adaptability of international markets.”