Why iron ore grade is now more important than ever

Pic: Schroptschop / E+ via Getty Images

Special Report: Declining iron ore grades globally and the rising demand from steelmakers for higher grade product is creating the perfect storm for explorers with the goods.

In Australia, hematite has been the dominant iron ore mined since the early 1960s, accounting for about 96 per cent of the country’s iron ore exports.

And since iron ore prices hit rock bottom in late 2015, the Australian iron ore market has largely been controlled by three of the world’s biggest miners — BHP (ASX:BHP), Rio Tinto(ASX:RIO) and Fortescue Metals (ASX:FMG).

But decades of mining is depleting the direct shipping ore (DSO) — the stuff that you can just dig up and ship — and buyers are now turning their attention to processed ores like magnetite.

There are two main types of iron ores – hematite and magnetite. Hematite is higher grade in the ground, while magnetite deposits are large and quite low grade – but produce very high-grade products.

Grade is king

Grade doesn’t mean much to those not in the mining game, but to producers there are several reasons why it is key to the profitability of their operations.

Iron ore mining is a high-volume, low-margin business that is capital eintensive and often requires big investment in infrastructure. So it’s crucial that a producer gets the best return from their product.

And that return varies depending on grade and demand.

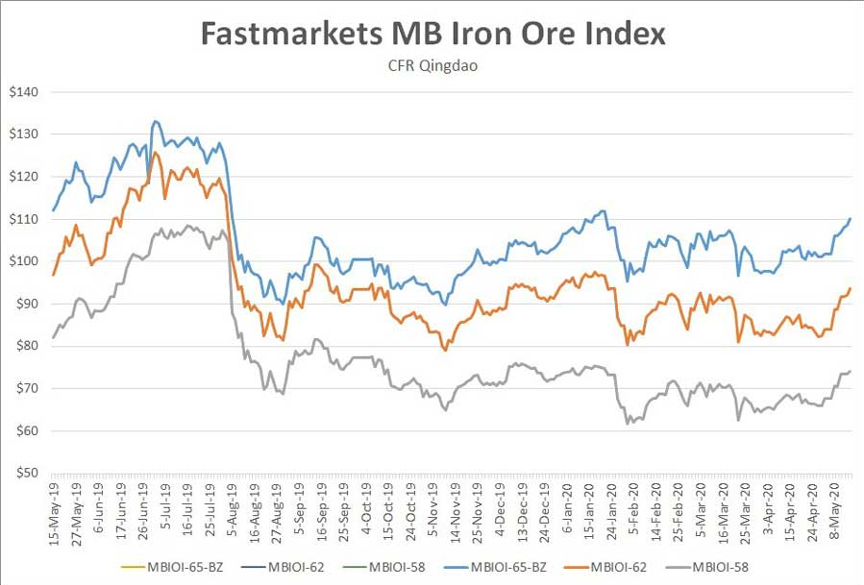

The iron ore price has been performing strongly in the past few months, and this week punched through the $US90 ($142) a tonne mark.

But that’s only for the stuff that grades 62 per cent. The lower grade stuff is sold at a big discount to that price, while anything higher than 62 per cent can attract a nice premium.

The big change since late 2016 is that the premiums for high grade and the discounts for low grade have generally increased.

“It is not unusual to see premiums of up to 30 per cent for the higher-grade Brazilian products or 15-20 per cent discounts for lower grade products,” Mark Eames, director of emerging producer Magnetite Mines (ASX:MGT), told Stockhead.

“This makes a big difference – Vale could be receiving $110 for 65 per cent products, the 62 per cent just over $90 and a 58 per cent product could be down at $75 a tonne in China.

“The means that Vale could be earning more than double the margins of a lower grade producer.”

But grades have been declining.

BHP produces over 62 per cent typically, while some lower grade products from Rio and Fortescue can be under 57 per cent.

“Whereas most of the average production out of the Pilbara probably 15 years ago was about 62 or 63 per cent Fe [iron], we’re now back down to probably an average out of Australia of about 59 per cent,” Eames explained.

“We’re seeing both BHP and Rio have experienced some challenges in their operations in the past two years and the grades at some of their operations have declined. Vale, the major producer of high grade, has faced plenty of challenges also.

“Fortescue has always had a grade challenge which is why they’re desperately trying to develop mines like Eliwana, which is going to lift their grades. But grade is becoming more and more of a challenge.”

Existing mine depletion

Along with grade reduction, many of the majors are seeing significant depletion in their reserves.

Rio, for example, has only about 2 billion tonnes of reserves at existing mines in the Pilbara, which is enough to sustain production for about six years or so.

And Fortescue has about 13 years or so of total reserves, which is still not a lot.

At the same time, very few new iron ore mines have been built or are in development, and the mines that are being built are largely replacing operations that are running out of ore.

Higher grade = less impurities

Pure hematite is about 70 per cent Fe. The rest is impurities that require energy to remove them in the iron making process.

The main impurities in iron ore are silica and alumina, which have to be melted out in the blast furnace to make slag with coke made from expensive coking coal.

Water (often indicated by loss on ignition, or LOI) and phosphorus are also particularly important.

Impurities reduce the productivity of the blast furnace and increase energy consumption, especially coking coal. Some impurities, such as phosphorus, are costly to remove and otherwise affect steel quality.

So it makes sense that steelmakers want higher grade ore with less impurities.

“There is a big difference between a 65 per cent ore and a 55 per cent ore – roughly three times the impurity levels,” Eames explained.

Brazil heavyweight Vale is the only one that can deliver a 65 per cent DSO product. But outside the company’s Carajas mine, the main source of higher-grade products is from beneficiating (washing or processing) the ore.

The magnetite advantage

This is where magnetite has an advantage.

“Magnetite ores often upgrade well, but Australia’s hematite ore types tend not to upgrade very well,” Eames noted.

As steelmakers look for high grade, especially when steel and coking coal prices are strong, there is potential for increased demand for high-grade magnetite and processed ores.

At the moment, high grade is just over a third of all iron ore sales.

Magnetite Mines is advancing the 4-billion-tonne Razorback project in South Australia, where iron ore has been mined longer than any other Aussie state.

Razorback is what Magnetite Mines dubs a “globally unique opportunity” and that’s because it has the potential to produce the highest grade of any iron ore operation in Australia as well as globally.

Lab tests undertaken by the company have already demonstrated it can produce grades of nearly 70 per cent from the Razorback project.

Globally there’s a bunch of big successful magnetite mines that have been producing for years.

China, US, Brazil, Canada and Sweden have been producing concentrate for years. Examples include Anglo American’s Minas Rio mine, which has a nearly 50-year mine life, Rio Tinto’s Canadian operations and Québec Cartier Mining Company’s mines, which now form part of the operations of the world’s biggest steel producer, ArcelorMittal, along with Champion Iron which is listed in Australia.

The high-grade players

According to Champion Iron, Brazil dominates the high-grade market, followed by Canada.

Australia, Sweden, Russia, Ukraine and South Africa all produce small quantities of high-grade iron ore, but collectively they produce less than 100 million tonnes — which equates to not much more than half of Fortescue’s production.

“There is one source remaining of natural high-grade direct shipping ore, which is the rich deposits of West Africa, especially Guinea,” Eames noted.

“But here again, the Australian players who did a lot of the exploration work (both Rio and BHP were active), have pretty much pulled out of Africa.”

Why Australia lags in the grade game

Iron ore is no longer just a tonnage game, it is now also a grade game.

But Australia is not well equipped to compete on the grade front right now, because despite more and more processing in the Pilbara, grades have been declining.

And attempts by companies like Karara Mining and Sino-Pacific to process hard magnetite ores have not gone well for investors and overshadowed successes, like Grange’s long-standing Savage River operation in Tasmania or Simec’s equally successful magnetite plant in South Australia.

READ: Busting the myth that magnetite can’t be profitable

“This is Australia’s challenge — unless we succeed in processing lower grade ores, it is a matter of time before our flagship iron ore exports come under pressure,” Eames said.

“Lower grade producers — such as Hancock’s Atlas operations, Rio’s Robe River operations and even some of FMG’s lower grade products — may well face heavily discounted prices.

“And in that market, it is the relatively high-grade producers who will get higher prices to offset their highest costs.”

Steelmakers in China need not just low-cost ore but reasonable grade.

Lower grade producers in places like India and Iran can’t sell some of their lower grades (often 55-56 per cent Fe products) at any price.

“So, the marginal producers of the future may well be the mines producing products under 58 per cent Fe, even if they have low costs,” Eames said.

>>NOW LISTEN TO: Explorers Podcast: MGT’s move for the 4-billion-tonne Razorback iron ore mine is perfectly timed

This story was developed in collaboration with Magnetite Mines, a Stockhead advertiser at the time of publishing.

This story does not constitute financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any financial decisions.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.