In bed with lithium: How to choose between hard rock or brines and where the strongest ASX prospects abide

Via Getty

- Hard rock – initially cost intensive, produces lithium hydroxide for battery makers

- Lithium brines – cheaper to develop, produce lithium carbonate

- Producing lithium from clays and geothermal brines is probably your Plan C

The market delights in the whiff of lithium right now, so it’s no surprise exploration results are under intense scrutiny as investors try to piece together who’s got what and if production is on the horizon.

There are two primary sources of lithium – hard rock and brine – and they both have their pros and cons.

Let’s walk through it together, at a trot.

Hard rock projects tend to be capital intensive initially but can easily produce lithium hydroxide which is currently commanding prices on the open market at around $US70,875/t.

Whereas your garden variety brine project tends to be less demanding in the set-up, less expensive to fire-up, but longer to get into production. Brines also produce lithium carbonate, which can be further converted to hydroxide, but at an added expense.

Lithium hydroxide (LiOH) and lithium carbonate (Li2CO3) are both used in battery chemistries, but hydroxide tends to command higher prices compared to carbonate which is a little lower at $US69,750/t.

Let’s break it down further, cantering.

The hard rock cafe

Hard rock spodumene mines have taken the mantle as the largest source of lithium raw materials thanks to the speed with which they’ve been able to ramp up in response to fast-moving prices and market enthusiasm.

Lithium found in hard rocks is typically hosted in ‘pegmatites’ which are intruding rock units that form when magma intrudes into the crust.

For those geology lovers out there, what happens is that as the magma cools, water and minerals are concentrated into metal-rich fluids that form the large crystals that define pegmatites.

These pegmatites typically form thick vertical sheets that can host ‘spodumene’ – a well-known lithium-bearing mineral – which usually outcrops at surface.

This is what the drill core looks like:

Grades of 1-1.5% considered the benchmark

Grades of above 1-1.5% lithium oxide – (Li2O) is produced by the thermal dehydration of lithium hydroxide – are considered the benchmark for drilling results.

The typical spodumene concentrate suitable for lithium carbonate production presents at around 6-7% Li2O

You can get grades above 2% like at the Greenbushes mine in WA’s South-West where even its tailings are so rich in lithium that at a grade of 1.3% the battery metal is found in higher concentrations than many primary mines.

But that’s generally considered an outlier.

For miners in the 1-1.5% spot, since lithium prices are so high, there’s also the option of pushing cut-off grades down slightly and going with a larger, lower grade deposit.

Metallurgy impacts project economics

It’s also important to remember the metallurgy of the deposit – which is how the ore is extracted, upgraded, or concentrated and then processed into the final product.

This stage directly translates to how economic the project is, because the cleaner the concentrate, the better the price the spodumene producer will get from the downstream processor.

The lithium hosted in spodumene can be processed into either lithium hydroxide or lithium carbonate.

You can also extract lithium from minerals like petalite and lithium micas like lepidolite and zinnwaldite but these sources can be lower grade and more complex than spodumene to process.

The lithium mineralogy may also be very fine-grained or inter-grown with quartz, which will impact processing and recoveries.

On the flip side, there could be associated tin or tantalum mineralisation that might provide by-product credits – particularly with tin prices reaching record highs back in March when they hit US$48,650/t before retracting back down around the US$43,000/t mark and tantalum in high demand in the semiconductor industry.

Hard rock lithium plays:

Last week the company raked in US$6188/dmt for a 5.5% Li2O cargo of spodumene in its latest auction – down from the US$7017/t 6% price received in a pre-auction bid last month – but still extraordinary given the first auction last July garnered a price of just US$1250/dmt.

It’s the first fall in prices since BMX platform launched but still five times higher than same time in 2021, but PLS fielded 41 bids in just 30 minutes.

At the third auction in October last year it saw 25 bids in a 45 minute window.

Regarded as the dregs of the Pilgangoora offerings (at 5.5% the product falls well short of the benchmark 6% Li2O grade used in spodumene benchmarks), that puts the sale at an equivalent price of US$6841/t.

At current prices the company’s margins are outstanding, with an FID on a major expansion of its Pilgangoora mine from 540,000-580,000tpa to 640,000-680,000tpa (and early investment in a potential expansion to a whopping 1Mtpa) complementing what is expected to be an almost $600 million cash build in the June quarter.

In May MIN announced plans to expand spodumene concentrate capacity at Mt Marion lithium project to 900,000 tpa of mixed grade product by end of 2022.

The company’s Wodgina JV operation with Albemarle is also making a comeback, recently producing the maiden concentrate from the first of its three 250,000tpa processing trains.

Another train is due to resume production in July while the JV’s Kemerton refinery is also nearing the end of its construction phase.

Late last month, the company and pal and Piedmont Lithium (ASX:PLL), approved a Canadian $98 million investment ($110 million AUD) to deliver a reboot of the North American Lithium operation in Quebec, Canada.

It will be the first local source of spodumene concentrate in North America, one of the three key markets for the global EV industry alongside China and Europe.

The mine is funded after recent capital raises from both JV partners, with concentrate production expected to begin in the first quarter of 2023.

It will produce 163,266tpa of 6% Li2O concentrate over a 27 year mine life, with a pre-tax NPV of $1 billion and IRR of 140% at a spodumene price of just US$1,242/t, well below the current market price.

Early this month, the company approved the $545 million development of its 500,000tpa Kathleen Valley mine in WA’s Goldfields.

Kathleen Valley is one of a number of operations and expansions slated to send either spodumene or lithium chemicals into the global market over the next three years.

Most of its output is already assigned for its first five years, ahead of a planned ramp up to 700,000tpa, to auto and battery giants Tesla, LG and Ford via offtake agreements.

Separately, Ford is providing a $300 million loan to back the mine’s construction.

Piedmont has three key projects – a development asset in North Carolina called the Carolina Lithium Project and they have two offtakes on other spodumene projects in Canada and Ghana in Africa.

And following the restart of NAL operations with Sayona, the offtake agreement with Piedmont entitles it to purchase the greater of 113,000 metric tons per year of spodumene concentrate, or 50% of production from NAL.

Prior to the NAL restart, the agreement provided for offtake of 60,000 tonnes or 50% of concentrate produced from ore mined at SYA’s nearby Authier Lithium Project.

PLS, MIN, SYA, LTR, and PLL share prices today:

Let’s talk lithium brines

Grab a cuppa because we are about to delve into lithium brines.

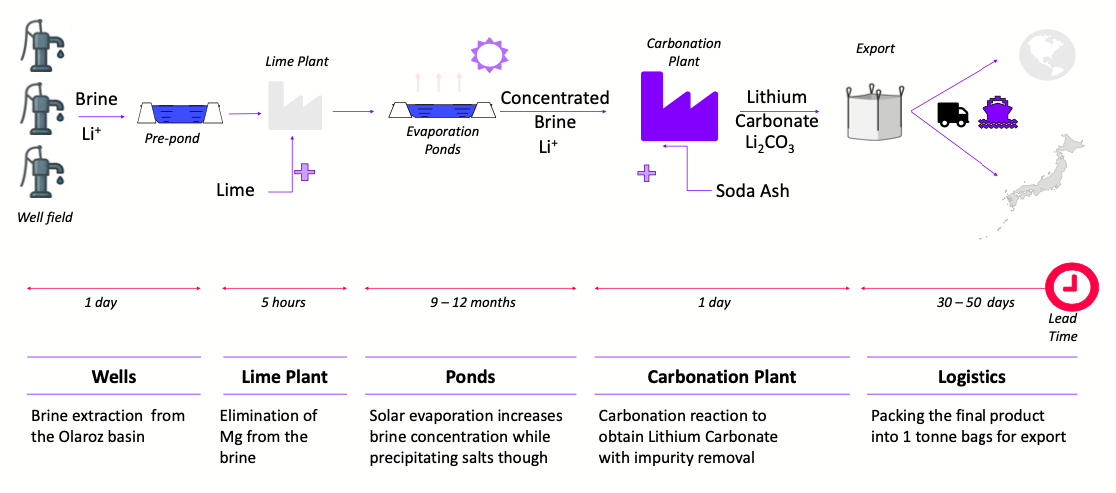

These deposits are accumulations of saline groundwater that are enriched in dissolved lithium, and the brine can be pumped to the surface to be evaporated in a succession of ponds.

Each transfer to a new pond achieves a higher purity until the brines are processed in a chemical plant between 1-2% lithium carbonate concentrate.

This can be further processed into lithium hydroxide – an extra step that translates into extra costs.

Brines are mostly found in Latin America in the famous ‘Lithium Triangle’ in the Andes mountains where Argentina, Bolivia and Chile meet.

And the reason for this is due to a combination of factors, such as the presence of source rocks known as acid volcanics and an area where water has historically run off these acid volcanics into a landlocked lake.

Measured in milligrams of lithium per litre

Brine projects are generally large in scale and low in grade, measured not in percentages but milligrams of lithium per litre of brine.

According to the US Geological Survey economic brines tend to measure between 200 to a whopping 4,000mg/L, but most significant operations tend to measure 400-600mg/L or above.

While brines have lower concentrations of lithium pound-for-pound compared to their hard rock counterparts, their comparative ease of extraction means that they generally have lower production costs.

And many players are looking to direct lithium extraction (DLE) as a more environmentally friendly process to produce cheaper, higher quality lithium because it eliminates the need for solar evaporation ponds, salt piles, and lime plants.

In a nutshell, the process involves a highly selective absorbent to extract lithium from brine water. The solution extracted from the brine water is then polished of impurities to yield high-grade lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide.

Plus, DLE also rejects critical impurities, yielding a higher quality product.

Brine lithium plays:

The company’s Olaroz project in Argentina contains an estimated measured and indicated resource of 1,752 million cubic metres of brine at 690mg/L lithium, 5,730mg/L potassium and 1,050mg/L boron for 6.4Mt of lithium carbonate and 19.3Mt of potash (potassium chloride).

But it’s also worth noting the company also has the Mt Cattlin spodumene mine in WA and yesterday AKE said that – despite some operational issues with grades, Covid, recoveries and stripping ratios – it produced a record 193,563t of spodumene concentrate in FY22.

The company says it expects to see relatively stable prices in lithium chemicals, carbonates and hydroxide and a continued increase in spodumene prices for the September quarter.

The company, which was spun-out from Strike Resources (ASX:SRK), is still at the early stages of exploration with work just about to start work on its flagship Solaroz project in Argentina to validate its current exploration target of between 1.5 to 8.7 million tonnes of contained lithium carbonate equivalent at between 500 – 700 mg/L of lithium.

The plan is to start with a a passive seismic survey to determine the maximum depth of the basement rocks before carrying out electromagnetic surveys to map out the conductive layers of lithium-rich brine.

This will be followed by drilling that will pave the way for resource definition.

The company says the brine development promises lower costs compared to hard rock, or spodumene, plays and a much lower impact on the environment thanks to its use of evaporation ponds that leverage energy from the sun.

Lake’s Kachi lithium brine project in Argentina currently has an inferred resource of 3.4 million tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent and an indicated resource of 1MT LCE.

Earlier this month the company retorted to a recent report by J Capital who it says put forth incorrect information on technical matters and inaccurate assertions on Lake Resources’ progress to-date with its technology partner Lilac Solutions for brine from its Kachi project in Argentina.

“The report’s description of Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) processes does not pertain to Lilac’s ion exchange technology,” Lake says. “It is criticising the wrong process.”

For the uninitiated, Lilac’s ion exchange technology is a chemical process where the targeted ion (lithium) in brine is exchanged for hydrogen in a charged media in the form of a ceramic bead.

The ion exchange process can be operated with zero net usage of fresh water by using small amounts of brackish water which is not fit for human consumption or agriculture and is available in large quantities at the Kachi site.

Pre-treatment of the brine to remove magnesium or calcium is not required as these ions are rejected in the ion exchange process.

The bead is then stripped of lithium using hydrochloric acid to produce an aqueous lithium chloride solution.

The company has three projects – the Candelas and Hombre Muerto West (HMW) brine projects in Argentina and the Greenbushes South hard rock project in WA.

Candelas North has a JORC resource of 684,850 tonnes of contained lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) at 672 mg/l Li (based on a 500mg/l Li cut-off).

HMW currently hosts a resource of 2.3Mt of lithium carbonate equivalent at a grade of 946mg/li lithium, the third largest disclosed resource in the rich Hombre Muerto basin.

The company recently completed pump testing at HMW, with brine sampling confirming a high-grade resource greater than 910 mg/L lithium.

“High lithium grades, porosity and brine flow rates are a powerful combination for driving operational efficiency and economic performance,” MD JP Vargas de la Vega said.

“These outstanding hydrological outcomes are paramount to the project DFS foundations and further validates the world-class nature of the lithium brine resource we hold at HMW.

Last week the company entered an Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Xiamen Xiangyu New Energy Co. for the development of the Salta project in Argentina.

Xiamen Xiangyu is a diversified Fortune-500, Shanghai Stock Exchange-listed (SSE:600057) supply chain and logistics company, providing an end-to-end supply chain for battery technology metals, sourcing supply of lithium, nickel, cobalt and other raw materials for processing plants and battery manufacturers and, end-use by automobile manufacturers and other battery technology industries.

“Xiamen Xiangyu is vastly experienced in the provision of closed-loop supply chain solutions for battery metals, and we look forward to working with them to fast-track the development of the Salta Lithium Project,” Power Minerals executive director Mena Habib said.

The parties will conduct due diligence investigations and enter negotiations with a view to executing a binding off-take, funding and logistics agreement for Salta project – which consists of five salares (salt lakes) that sit within seven mining leases, over a total project area of 147.07km2.

AKE, LKE, LEL, GLN, and PNN share prices today:

Other lithium sources worth a mention

With the growth of the EV sector, geologists are looking for lithium from more sources to increase supply of the raw material.

Some that have been proposed include clay-based lithium mining and geothermal brines, which would tap rich but low-grade lithium salts within deep wells of geothermal fluids typically used for heating and energy.

However commercial scale production is yet to be realised, which means financiers have tended to favour ‘lower-risk’ investments in lithium mineral or brine projects.

In clays you’d expect to see anything from 800ppm to 2600ppm Li as a resource grade with intercepts of up to ~0.5% Li2O.

Then there’s the potential to extract lithium from petroleum brines. An approach that focuses on concentrating lithium and other elements from abundantly available wastewater (brine) that accompanies oil and gas production.

There are also some outliers, like Rio Tinto’s (ASX:RIO) Jadar deposit, which may never get built due to community opposition in Serbia. That is a planned underground mine with a mineral seen in few other places called jadarite that bears similarities to clay-based deposits.

According to Rio, Jadar contains 85.4Mt of indicated resources at 1.76% Li2O and 16.1% B2O3 (boron) with an additional 58.1Mt of inferred resources at 1.87% Li2O and 12.0% B2O3.

Unconventional lithium plays:

This company owns the Rhyolite Ridge project in Nevada and plans to extract lithium and boron from searlesite and says it is the only known lithium deposit associated with the boron rich mineral.

Based on a DFS completed in 2020, Ioneer claims the development will have the lowest all in sustaining costs globally for lithium hydroxide production of just US$2510/t from a large resource of 146.5 million metric tonnes of lithium and boron and ore reserve of 60.2Mt at 1800ppm lithium (equivalent to 1% lithium carbonate according to Ioneer) and 15,400ppm boron (8.8% boric acid).

The highest grade interval at Rhyolite Ridge was 18.5m at 2364ppm lithium and 13,044ppm boron.

AZL is currently waiting on the US Bureau of Land Management approval for the drilling of 145 exploration holes and a bulk sample program at its Big Sandy project in Arizona.

The project as a very shallow, flat lying mineralised sedimentary lithium resource, which the company says has the potential to be developed with a very low environmental footprint.

AZL’s 2019 drill program at Big Sandy resulted in the estimation of a total Indicated and Inferred JORC resource of 32.5 million tonnes grading 1,850 ppm Li for 320,800 tonnes Li2CO31.

This represents 4% of the Big Sandy Project area that contains an estimated exploration target of between 271.1Mt to 483.15Mt at 1,000 – >2,000ppm Li2.

The scoping study for the project is currently underway, with recent test work showing a lithium leaching extraction from the concentrate of 88% and production of at least 99.8% battery-grade lithium carbonate.

The company’s Zero Carbon Lithium Project in Germany’s Upper Rhine Valley aims to produce lithium by pumping deep geothermal brines to surface, using the excess geothermal energy to power its lithium chemical process and export additional power to the grid.

And recently, they signed an agreement with the largest geothermal energy producer in Italy Enel Green Power (EGP) to explore and develop geothermal lithium in Italy at Vulcan’s Cesano license in Italy through a joint scoping study.

In Thailand, infill and extensional drilling is ongoing at the Reung Kiet lithium prospect with a mineral resource upgrade and scoping study expected later this year.

The company is confident there is extensive lithium mineralisation hosted in lepidolite rich pegmatite dykes-veins – plus the project is in an underexplored tin-tungsten belt so those by-products could add revenue to any future operations.

INR, AZL, VUL, PAM share prices today:

At Stockhead we tell it like it is. While Arizona Lithium, Lithium Energy, Galan Lithium, and Vulcan Energy are Stockhead advertisers, they did not sponsor this article.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.