Tin prices are at record highs. Here’s why they could double again

Pic: Getty

A tin expert and metals trader who played the last tin cycle as a hedge fund manager with Trafigura says the tightly strung market could see prices bound beyond current record highs to as much as US$80,000/t.

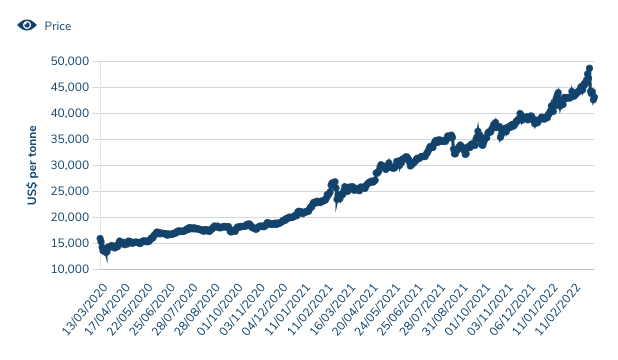

London-based ‘tin guru’ Mark Thompson made the call recently as the three-month tin contract on the London Metals Exchange hit a record high of US$48,650/t on March 8.

It is now fetching around US$43,000/t, a near tripling of prices over the past two years.

Thompson had a previous price target of US$30-35,000/t to incentivise new production of tin, which is in extremely short supply with just days of stock left on the key London and Shanghai metal exchanges.

But that hasn’t happened, and a ‘perfect storm’ is brewing that could push tin prices into a new paradigm.

#tin – Change of View:

I am moving my long term price prediction on tin from the $30k – $35k where I was sat to $50k – $80k. New information has come to light to force me to do so.— Mark Thompson (@METhompson72) March 7, 2022

He told Stockhead his new target is US$50,000-80,000/t, with higher than expected inflation and the rapid growth of electric vehicle production behind the change in outlook.

This ain’t your ordinary base metal

LME base metal prices have come into sharp focus in recent days after the extraordinary price run in nickel, caused by the withdrawal of Russian supply after its invasion of Ukraine and a mega short squeeze.

But Thompson says tin is no nickel.

“Tin’s a very different metal from nickel, in terms of who uses it as a contract, volatility and other characteristics,” he said. “So, there’s very little different speculative interest in the tin market, it’s by far the smallest of the LME metals.

He said there are no producers in the tin market who would build a derivative position like the massive short that Tsingshan took out which exposed it and its bankers to billions in trading losses and margin calls.

“So it’s very fundamentally driven at the moment, the price I think genuinely reflects the fundamentals,” Thompson said.

“You know, we’ve got close to zero stocks, both on Shanghai and on the London Metals Exchange, and we’ve got very, very reduced producer and consumer stocks. So the tin price I think, right now around US$50,000 a tonne fully reflects the fundamentals.”

To infinity and beyond

But the “perfect storm” beyond that is coming into clearer focus as well.

“So over the last 10 years, the price has averaged around US$15-18,000 a ton,” Thompson said.

“And my long term price forecast was US$30-35,000/t on the basis that was the incentive price you needed to basically finance the additional production that was needed from new hard rock mines.

“The reason why I’m now saying US$50-80,000/t is one is I believe that inflation expectations are now firmly entrenched, that money is going to be worth less going forward than I previously had in my model.

“And then on the demand side, really it’s very much I had underappreciated how much additional tin goes into electric vehicles.

“So it’s not just the additional tin in the lead acid battery, the KERS system in an electric car, the kinetic energy recovery system, is based on capacitors which have a vast amount more tin joining them together.

“So a new-build electric car has about one and a half kilos of tin in it compared to an existing one, which has about 300 grams. So there’s a vast amount more tin demand to come from the electric mobility sector, that puts the market just even further into deficit.”

Why higher tin prices won’t hurt demand

Tin is commonly known as the ‘spice metal’ because a little bit of tin is in virtually everything.

But it tends to be found in such small quantities that demand is relatively inelastic.

Around half of global tin supply goes into solder for electronics. While it’s a key component it is a tiny fraction of the raw material cost of most consumer items.

Thompson says while the world is tipping hundreds of billions into expanding semi-conductor production, it has neglected to invest in new tin supply.

“We’ve got almost nothing in the supply chain in terms of new projects coming on stream anytime soon,” he said.

“We’ve got background global economic growth, which is on a sort of 2% consumption growth, and particularly coming from the electronics sector, which is growing at somewhere between 9-14%.

“The world has committed, I think, of the order of US$600 billion to new semiconductor capacity. So far, the world has committed $0 for any new tin capacity for the solder to join those electronic components together.

“And then on top of that, you’ve got the green energy revolution which will potentially add another 2-3% per annum demand growth, maybe even quite a bit more than that. And basically that cannot happen.

“There is zero probability, zero, of the tin market growing by 100,000 tonnes of supply by 2030.”

The one gram of tin in an iPhone retailing for thousands of dollars is worth just 5c even at current high prices, Thompson said.

“There is no tin price where Apple will stop making iPhones,” he said.

“You’ve got about five to eight grams in a washing machine, so you’re talking about 25-50c of tin in a $500 item. There probably isn’t a tin price where Bosch stops making washing machines. So it’s highly, highly inelastic demand on the electronics sector.”

It is also virtually unsubstitutable in most applications.

They include tin sulphide, a chemical used to stop plastics decaying in UV sunlight, tin cans, which have a thin layer of tin bearing anti-microbial properties worth just 1.8c which has not been bettered since the Napoleonic Wars, lead-acid batteries, specialty alloys like bronze and the Pilkington Process, used to make flat glass.

“It’s a fairly unique metal, multiple uses in billions and billions and billions of consumer items in very small quantities and very small value amounts. So because of that profile the price really pretty much could go to anything,” Thompson said.

No new supply

The International Tin Association says global tin smelters produced around 378,400t of tin metal in 2021, 11% up on the pandemic affected 2020 (339,400t), against consumption of around 390,000t.

Barring further Covid related issues (though the virus has recent re-emerged in China), production is expected to grow 4% in 2022.

Despite that, Thompson said producers were not switching the taps on quick enough to keep pace with demand.

“So you’re really looking at the informal sector. So we’re looking at additional artisanal production, Indonesia and the DRC,” he said.

“Now, the tin price has already gone from US$15,000/t to US$50,000/t and we’re really not seeing very much of a supply reaction, mainly because these assets are old and nearly exhausted. So the answer is no, I don’t see any sort of supply reaction.”

In fact, he thinks existing producers are showing supply discipline to ensure they run assets longer at higher prices, particularly from miners in Indonesia.

“I think there’s a genuine understanding out there in the tin producer market that, I’m not gonna say they’re going to sell half as much, but you can sell less at a higher price,” Thompson said.

“The kind of idea that you can sell half as much at twice the price or twice as long is a sensible business strategy. So I think the production community also knows this is a rare and valuable asset.

“And you don’t need to sweat them for cash today if this green energy revolution is around for the next few decades. There’s an awful lot of money to be made by keeping tin in the ground rather than mining it.”

Tin producers to ride the wave

Among Thompson’s sector picks is TSX-V listed Alphamin Resources, which claims to mine around 4% of the world’s tin at its Mpama mine in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

“So you’ve got Alphamin in the DRC, which is producing in the order of 12,000t a year; it’s a truly great orebody,” he said.

“I think it’s very much bigger than the existing resource has in it.

“They’re mining 4% tin which at the current price is a 20% copper equivalent, I mean this is a really super high grade deposit.

“Their issues are not grade or tonnes, but they are issues of security and logistics, because they are in the middle of North-Kivu in the DRC. They may well increase production, I would like to see them show some supply discipline and be producing less for longer at a much higher price.”

In Australia, Metals X’s (ASX:MLX) Renison-Bell tin mine in Tasmania continues to be a strong contributor more than 130 years after its discovery.

It produced 8,452t of tin in concentrate at all in sustaining costs of $22,248/t in 2021.

“I think it’s got a few more decades left in it, just a consistent producer,” Thompson said. “The mill is quite old, but they’ve done some upgrades recently and I think I wouldn’t discourage anybody from having a look at that as a potential investment.”

London listed AfriTin runs the smaller scale Uis mine in Namibia.

A new float is also coming to market with a planned listing in London called First Tin. Thompson is a director.

It has projects in Germany and Australia, including the 57,000t Taronga project in New South Wales purchased for $34 million, mostly in shares, from ASX-listed Aus Tin Mining (ASX:ANW) last year.

“We’ve got an advanced tin asset in Australia and an advanced tin asset in Germany,” he said.

“And I think they’re going to probably be the next two hard rock tin mines to come to market.

“And what’s special about both of those is our production costs are sort of in the US$10-15,000 a tonne region as opposed to the US$30-35,000/t most new tin mines are going to require.”

Metals X share price today:

Thin pool of explorers to chase tin growth

Given the small size of the tin market and its rarity there is only a small pool of explorers to bet on in the Australian space.

One, Venture Minerals (ASX:VMS), owns the relatively advanced Mount Lindsay tin and tungsten project near the Renison mine in Tasmania.

The junior started exploring the asset 15 years ago and has spent $35 million on exploration including 83,000m of drilling, but it faded into the background after a 2012 open pit feasibility study as tin prices declined.

Now that prices are at record levels and tin is beginning to emerge as a critical metal for the green energy revolution, Venture is more bullish on its flagship asset, which contains 81,000t of tin metal and 3.2Mt of tungsten at a tin equivalent grade of 0.4% at a 0.2% cutoff.

It is working on a new study on developing an underground mine at Mount Lindsay with the ESG benefit of its connection to hydro power.

Venture Minerals MD Andrew Radonjic said he wasn’t surprised to see predictions that prices could increase further given tight supplies and the International Tin Association’s prediction at least 60,000t more tin a year will be needed for electric vehicles by 2030.

While the feasibility study won’t be released until later this year Radonjic said previous underground scenarios showed Mount Lindsay “looked quite attractive at half this price.”

“We think we’re in a sweet spot for a number of reasons,” he said.

“One is we’re on the west coast of Tasmania in a tin district and we’re surrounded by old tin mines and Australia’s only tin mine in Renison-Bell.

“We’ve already spent $35 million on our project, we’ve got hydro power running through our tenement which ticks a big ESG component, we’ve already decided to go underground.

“There’s a lot of reasons why the world needs a lot of tin, but investors are demanding ESG-compliant tin and that’s where I see a sweet spot in the market.”

Elsewhere silver explorer Thomson Resources (ASX:TMZ) owns the Bygoo Tin Project in New South Wales, which surrounds the Ardlethan mine, the Aussie mainland’s largest tin producer historically at 31,500t.

Brisbane’s Elementos (ASX:ELT) is also working on a DFS on its flagship Oropesa project in Spain, as well as the Cleveland tin project in Tasmania.

Elementos’ shares rose on filings yesterday showing it had identified new mineralisation outside its existing resource at Oropesa. An “optimisation study” is due out this month.

Stellar Resources (ASX:SRZ) also has an early stage project in Tasmania at Heemskirk.

ASX tin stocks share prices today:

At Stockhead, we tell it like it is. While Thomson Resources and Venture Minerals are Stockhead advertisers, they did not sponsor this article.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.