School of Rock: Here’s how to read oil and gas announcements

Picture: Getty Images

Reading announcements from oil and gas companies can seem daunting at first due to the amount of jargon contained within.

Terms such as 2D seismic, MMbbl, Bcf, petajoules and MMBtu abound and sometimes seem to be used interchangeably, which just adds to the confusion.

Like our companion piece on how to read mining announcements, Stockhead will attempt to cut through the jargon and explain what you’re reading.

Where to drill

Exploration is the bread and butter of junior oil and gas companies, so understanding what a company has found and how it got around to doing so is key to making investment decisions.

Before any of drilling is carried out, explorers first need to know where to sink their drill bits.

This stage is typically carried out by governments looking to attract investment in their resources and can consist of mapping work, geochemical sampling and geophysical surveys, which typically consist of seismic surveys but can include gravity, magnetic and resistivity surveys.

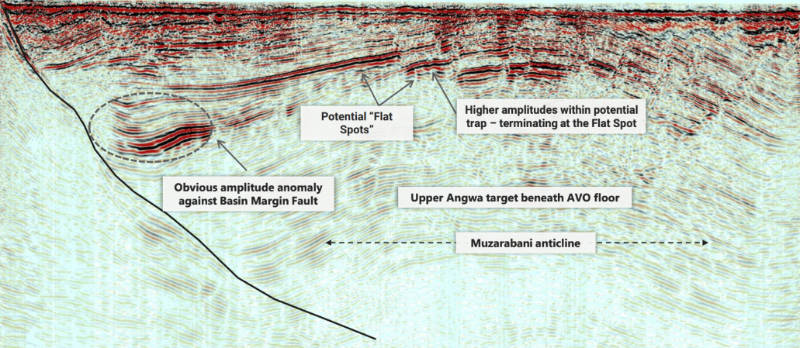

Seismic surveys are the primary geophysical method to image the subsurface for prospective reservoirs in both land and marine (onshore and offshore) environments.

Two main varieties are used.

2D seismic, which is acquired along a single line to create a single cross section image to provide an idea of what structures are present.

And then we have the considerably more expensive but also far more informative 3D seismic that uses crisscrossing lines to create a cube allowing for imaging from any angle – essentially a 3D image.

This provides companies with the information about the layering and nature of rock under the earth’s surface, which in turn allows them to determine which are the likely places that oil or gas maybe trapped.

Read here for so much more on traps and reservoirs.

Drilling results

Once the target reservoir has been identified, the company will then move to drill the exploration well.

This is when things get really interesting (and confusing) for investors.

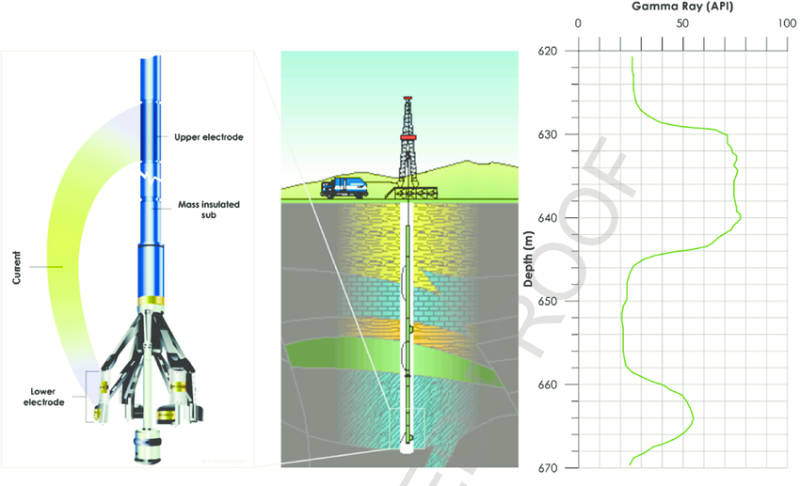

Tools that form part of the downhole assembly – the bit that actually does the drilling – allow explorers to carry logging while drill (LWD), which lets them see what the properties of the rock or formation that the well just drilled.

Here’s where some of the early exploration data starts becoming available that can give a sense of whether the well has intersected anything interesting.

The first sign that drilling has encountered anything of interest is ‘oil shows’ and/or ‘gas shows’ with the latter measured against background levels.

Drill cuttings from the well bore which demonstrate the right type of fluorescence when exposed to UV light can also be a useful indication that oil is present, the type of oil it might be and whether it is mobile.

Wireline logging will often be carried out as well to determine the porosity of the reservoir, the saturations of oil and gas (or sometimes water) and the vertical extent of the productive hydrocarbon zone – often referred to as net pay.

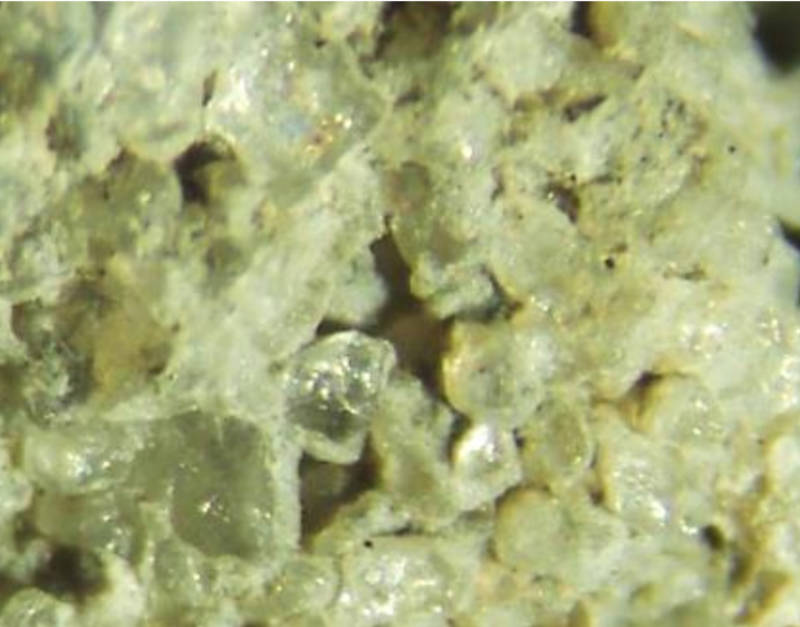

Porosity and permeability are also important factors in determining if a discovery can produce oil and gas commercially.

Commercial reservoirs typically have porosities – the tiny spaces between rocks – of at least 8% for oil and somewhat less for gas.

The other half of this equation is permeability, which is the capacity of a rock layer to transmit fluids such as oil. This is measured in millidarcy (md) with a value between 100md and 500md being considered reasonable.

Pressure is often quoted as well and a combination of high porosity, permeability and pressure is a likely recipe for commercial oil and gas flows.

Figuring out if the intersected reservoir can flow is the province of drill stem testing and/or flow testing, which is the final arbiter of whether a discovery is commercial or not.

Oil flow is measured by the barrel, which equals about 159 litres, while gas is commonly measured in cubic feet though some companies like to measure by the gigajoule or petajoule with 1 petajoule being roughly equal to 947 million cubic feet.

Some of the commonly used acronyms include MMbbl (million barrels), bcf (billion cubic feet), tcf (trillion cubic feet), MMcf (million cubic feet), and Mboe (million barrels of oil equivalent).

And just to add a little bit of confusion, some companies use million British Thermal Units (MMBtu), which is roughly equal to a 1000 cubic feet. Incidentally, a single thermal unit is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit.

Resource/Reserves

Besides the exploration part of the equation, a common issue faced by oil and gas punters is understanding exactly what companies mean when they define resources.

First off is in-place estimates. These are truly pie in the sky figures that represent the total amount of oil and/or gas that could be contained within a reservoir prior to any drilling.

While it might be a useful point from which to decide if a reservoir is large enough to go through the effort of drilling, it in no way guarantees that any oil or gas might be present, much less in commercial quantities.

That doesn’t mean it come have a big impact on company share prices. A notable example of this came about when Bass Oil (ASX:BAS) announced on 16 November 2022, an absolutely massive potential in-place resources of 21Tcf of gas and 845 million barrels of oil – after correcting an error with a completely implausible 845 BILLION barrels of oil – in its PEL 182 permit in South Australia.

Despite the early nature of this in-place resource, the news was enough to send shares in the company soaring 138% to 8.8c.

Prospective Resources are just a little bit more certain than in-place estimates and are typically defined as the potentially recoverable amount of hydrocarbons from undiscovered accumulations.

This is also sometimes seen in coal seam gas where the characteristics of the target coals are well known, allowing companies to make an educated guess of what they could have.

Where things get a lot more interesting is when explorers start talking about Contingent Resources, which are when discovered accumulations are still at an early stage or where there is currently no viable market.

Contingent Resources are further divided into 1C, 2C and 3C categories with 1C being the most certain while 2C, or best estimate, is the most commonly considered to be what is potentially recoverable.

The greatest level of certainty come in the form of Reserves, which is the quantity of oil and/or gas that are anticipated to be commercially recoverable.

A notable example highlighting the difference between Prospective and Contingent Resources stems from TMK Energy (ASX:TMK) reporting on 9 November 2022, a 1.2Tcf 2C Contingent Resource for the Nariin Sukhait area where it had just completed a successful exploration program that sent its shares up more than 90% from mid-September.

This is in addition to the somewhat lower confidence best estimate 2U Prospective Resource of 5.3Tcf that is estimated to be present within in other regions within its broader Gurvantes XXXV project.

Proved, or 1P, Reserves are those quantities which can be estimated to more than 90% certainty to be commercially recoverable from discovered reservoirs and under current economic conditions and operating methods.

Probable (2P) Reserves have at least 50% probability for recovery and is often the figure used for investment decisions.

Possible (3P) Reserves have the lowest possibility for commercial recovery though it remains a good indicator of just how much potential the reservoir hosts.

As for resource sizes, a 100MMbbl oil reserve is pretty substantial but even smaller oil discoveries can be commercially developed if they are located near existing infrastructure or have ready access given that oil can just be trucked or transported by rail.

Gas discoveries tend to require significantly more infrastructure to develop and as such, most of the offshore discoveries tend to be fairly large (in the tcf range).

Onshore gas finds can be developed at much lower cost if they are close to existing pipelines.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.