4 US debt ceiling scenarios you can sing to, including the one where the S&P500 crashes 30pc

News

News

I have a soft spot for the man behind everyone’s problems, US Fed Chair J Powell.

The buck, literally, stops and starts with the 16th Chair of the Federal Reserve Bank. His is the responsibility for the health of the American – and consequently the global economy. Yet, like a brain surgeon with a butter knife and a hammer, Powell’s got the bluntest of instruments to deal with the most complex of problems.

He has all the power, none of the control.

Really, his job – like our own Reserve Bank boss, Dr P Lowe – is to jawbone. It’s his language, his very choice of adjectives which truly guide the ebb and flow of money markets.

Once a month, working professionals as unqualified and distant from the foibles of global finance as I am, still have to dedicate a lost hour of their lives to sifting through and translating the granular wording of the various statements on monetary policy and deciphering what it might mean about the true economic mood of the man.

Which is why, when he speaks like an angry cop about the US debt ceiling thing, we can only hope the Americans can hear him.

“No one should assume that the Fed can really protect the economy and the financial system and our reputation globally from the damage that such an event might inflict,” Powell said earlier this month when asked how the central bank could save the day, should the worst happen.

A government default – the first in US history – would be “unprecedented” and result in “highly uncertain” and widely “diverse” calamities for the economy, he said on May 4.

“We shouldn’t even be talking about a world in which the US doesn’t pay its bills,” Powell said.

“It just shouldn’t be a thing.”

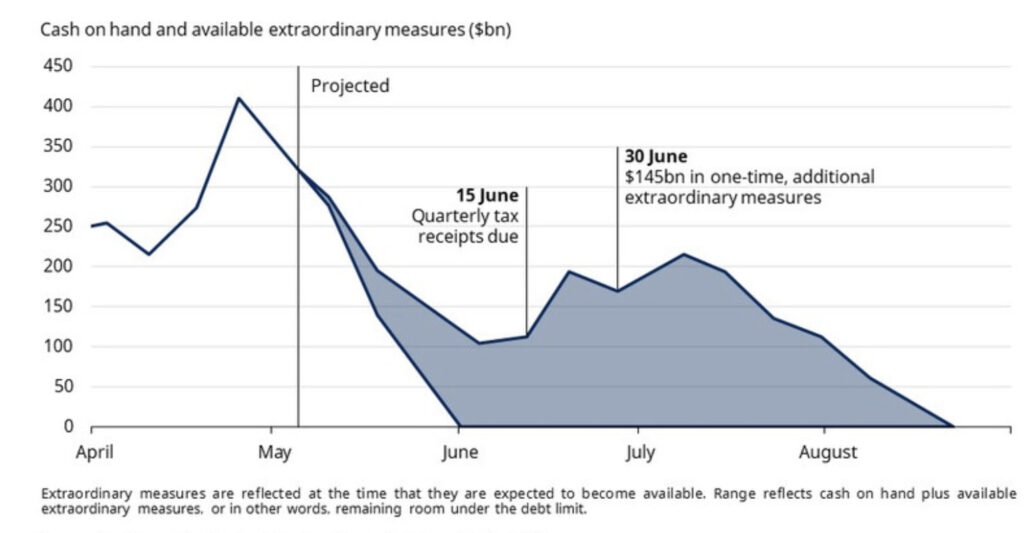

According to the US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, “X-date” – that is when the US starts defaulting on its innumerable payment obligations, all because Congress won’t sign the cheque – begins June 1.

The X-date marks the point of no return, where the fabulously cashed up Treasury of the world’s most fabulously wealthy nation runs out of funds.

While negotiations flounder, Schroders economist George Brown says the first dominos to fall when X-date passes without the debt ceiling being raised is essential coupon payments and redemptions of Treasury securities will stop.

“While technical lapses have occurred – such as the 1979 check-processing glitch that delayed some redemption requests – a true default would be an unprecedented event with far-reaching ramifications.”

The States had disappointing tax receipts during a lean 2022, and Brown says that leaves a lot hinging on how revenue shapes up through this month.

The hope was maybe the government’s quarterly tax payments could sustain the US through much of July and perhaps even to August.

But now that Yellen has called X-date for June 1, those receipts, fat as they might be, aren’t due to hit the accounts until mid-June.

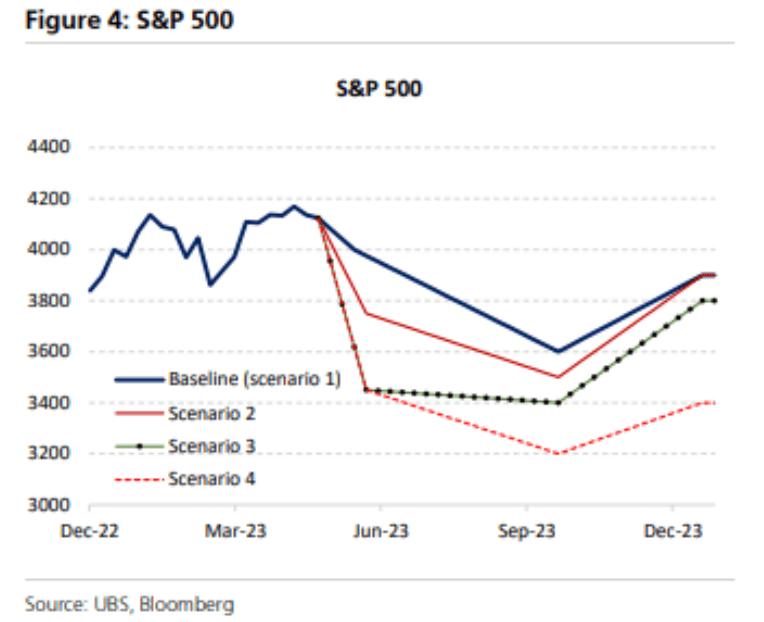

UBS have conveniently whittled down the future into four prospective timelines.

Base Case (let’s call this Scenario #1)

UBS are expecting the S&P500 to drop 5% by the end of this quarter, and end the year roughly flat at 3,900, after negotiating a trough towards 3,400 in Q3.

Scenario 2:

If the June 1 X-date is crossed without a formal default, but the US government has to prioritise payments, UBS see the drop in Q2 deepening a further 5% to 3,750, but proving temporary.

Scenario 3:

A one-week period of no coupon payment and default would trigger up to a 20% drop in stocks towards 3,400 and keep them suppressed at those low levels through Q3 before making a partial recovery towards 3,800 by year end.

Scenario 4:

The very unlikely scenario of a month-long non-payment of coupon would not only cause an immediate drop of up to 30% in stocks, but it would also see a very weak recovery, the S&P500 ending 5% below current levels even by end ’24.

UBS see European equities, which have done pretty good in 2023, outperforming the S&P500 through all the above scenarios of US debt ceiling uncertainty.

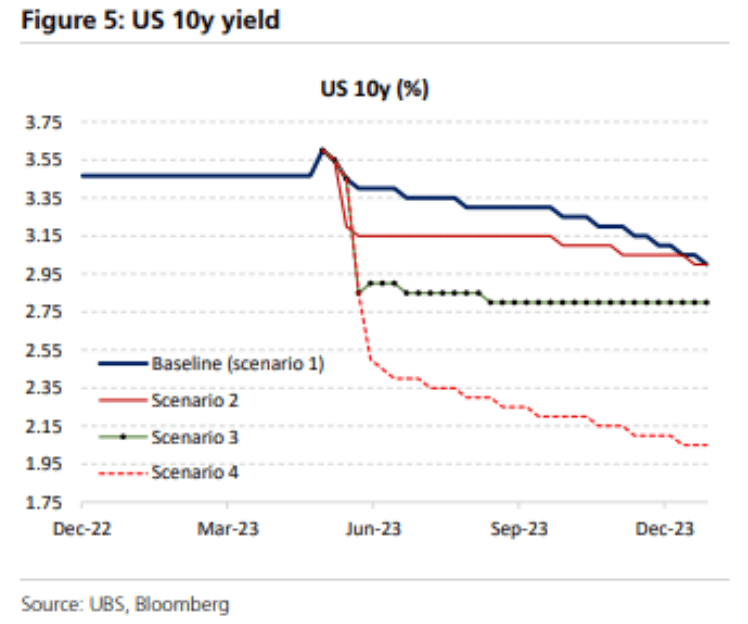

US yields will fall, not rise, even if the US defaults on its debt obligations, the investment bank says.

Treasuries’ flight-to-quality status comes more from liquidity than from credit quality, and the downswing in the economic cycle should overwhelm the rise in term premia (the compensation investors require for bearing the risk that interest rates may change over the life of the bond) that likely follow missed coupons.

The message from Schroders to its investors is blunt: hope for success, but plan for failure.

“Where possible, portfolios ought to be liquid and diversified to ensure capital can be redeployed quickly given the volatility seen during prior episodes of debt ceiling brinkmanship. However, it would be a mistake to assume that assets will perform as they did before. For instance, the rally in Treasuries during the 2011 standoff coincided with concerns about the eurozone debt crisis.

“While it is conceivable that Treasuries could perform well over the coming weeks, this is by no means guaranteed,” Brown says.

“Our strongest conviction is to have an overweight allocation to gold, even in spite of the recent rally, as well as towards AAA-rated sovereign issuance such as German Bunds. Alongside this, we would also expect safe haven currencies such as the Japanese yen and the Swiss franc to perform well against the US dollar.”

Stock markets is where the bleeding will be most profuse.

“Equities will probably find themselves under the most pressure,” Brown agrees.

“But there is likely to be a wide divergence beyond the headline indices. Companies that have a heavy reliance towards US government spending or subsidies are likely to come under the most pressure. Whereas value stocks could hold up better, as should defensive and non-cyclical sectors such as pharmaceuticals.”

Drugs are not the answer. Except, it seems, in this case.