The Kouk, the Quackery and the Morrison-Lowe conspiracy of pain: a read on rising Aussie cash rates

News

News

As widely expected the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has maintained its smashingly low cash rate at 0.10%, sticking to its ask questions first, shoot everyone later policy in the face of the federal government’s recent election-flavoured fascination with what it’s been saying is the onerous cost of living for ordinary Australians.

I for one, am as ordinarily Australian as they come. According to the most recent Census of Population and Housing – a pre-pandemic read on what really divides Australians – there were some 8.3 million households in Australia. I’m among the 67% (5.4 million households) who own a home and within that cohort, Mme Edwards and I are among the 35% (2.9 million households) with a mortgage.

After that, the census says there’s about 2.6 million Aussie households – about 32% – who were renters.

So at 2.30pm on the first Tuesday of the month – a special day which only comes around 11 times a year – the top brains at the RBA get together over coffee and biscuits to hammer out what they need to do with how much money costs.

And as economists and the educated elite broadly predicted, the central bank’s best and most vigorous economic thinkers chose to keep the cost of borrowing at the delightful, bargain interest rate of 0.10% a record low which has been the way of things since back in November 2020.

The RBA has long maintained that it would require inflation to be “sustainably in the 2 to 3% range” before it would consider lifting rates, but this week, in his statement on monetary policy, the RBA Governor Philip Lowe flew a few significant guidance flags, flashing lights and smoke signals indicating the bargain cost of borrowing is over and rising rates are coming faster, if they’re not already in the post.

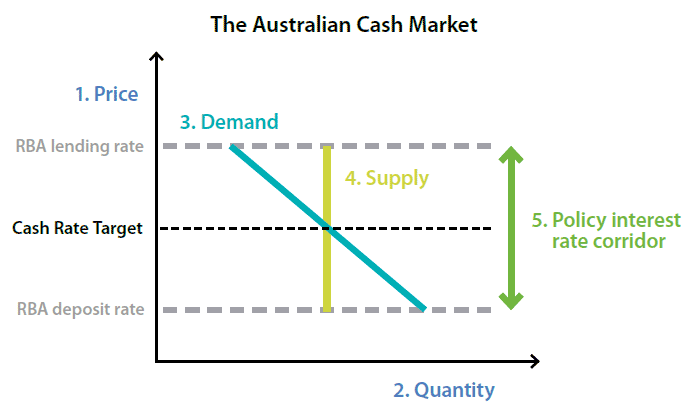

This should make it clearer. In the words of the RBA:

How the cash rate target is implemented can be explained through five aspects of the cash market: the price, quantity, demand, supply and the policy interest rate corridor.

The juggling act here for Dr Lowe is measuring the pace of looming headline inflation, currently at 3.5%, against an increase in the cost of borrowing, which economists of all stripes – including the grey ones at the RBA – agree places pressure on the government’s bruised and bewildered households, already burdened by mortgage pain and the various fiscal ailments that come under the generally horrible cost of living in Australia.

And yet, for the first time since Covid, and amid an improving economy, rising inflation, geopolitical tensions and rising global yields, the RBA has conceded that a rate increase this year is totally on the cards.

“Housing prices have risen strongly over the past year,” Governor Lowe said in the RBA’s statement, “and while some housing markets have eased recently… with interest rates at historically low levels, it is important that lending standards are maintained and that borrowers have adequate buffers.”

He’s worried that a country so married to its mortgages will implode if the bank springs a rate rise on us – which is why Tuesday’s announcement was rich in central bank smoke signals.

In anticipation of it, Barclay’s research overnight brought forward its first rate hike call to July (from August) and now see more rapid increases in the official cash rate (OCR), to ensure it hits 1.50% by the end 2023.

“We think the removal of ‘prepared to be patient’ from the statement was a nod to market participants expecting hikes starting in H2 22,” the Barclay analysts said.

“Indeed the focus from today’s meeting was on the RBA’s dropping of ‘patience,’ with the OCR hold largely a given.”

Stockhead asked the indy economist Stephen Koukoulas if the fear campaign over rising rates was worthy of the RBA’s – and therefore everyone else’s – agonising.

The straight-shooting MD of Market Economics described a major disconnect in the way the central bank, the government and a lot of economists are measuring pain and inflation.

“Look. From a starting point of 0.10%, anyone who has financial stress with, say, 1.0-1.5 percentage points of hikes has had their head in the sand,” The Kouk said.

“I suspect there are very few in this boat, even though everyone with debt will moan about the hikes. And If you assumed rates would stay at 0.10%, you only have yourself to blame as rates rise.”

Moreover, The Kouk told Stockhead, the vast bulk of Aussie mortgage holders are simply miles ahead in their repayments, having ridden the rate cutting cycle of the last decade lower.

“For many, the first few hikes won’t touch the sides, they will not have to allocate cash to the higher repayments as they are already ‘overpaying’ having taken out their loan when rates were 100-300 bps higher.”

With inflation back on the menu, the country at full employment and – finally – wages poised to surge, the ‘ordinary Australian’ is going to be better armed to stave off what Mr Morrison and the broader economic community is painting as the agony of living in Australia in 2022.

“These are a powerful offset to any hikes.”

That said, The Kouk is also not a fan of what he calls the quackery of the central bank.

The quackery of the RBA:

2020: 0.1% cash rate needed – end 2022 unemployment forecast to be 6%, inflation 1.5%.April 2022: 0.1% cash rate needed – end 2022 unemployment forecast to be 3.75%, inflation 4%.

WTF is it smoking? Or it is just political bias?

My Two Minute Take pic.twitter.com/nBZBwjtgU2— Stephen Koukoulas (@TheKouk) April 5, 2022

“The RBA is playing some interesting games – it’s either mis-reading the economy or it’s trying to bluff its way through to the post election environment so it’s not seen as having a political bias… but the longer it waits the worse the pain it will inflict,” The Kouk says.

On the fear and loathing being drummed up around rising rates, Diana Mousina, senior economist at AMP Invest, says it’s actually less about the cost of living in Australia, and more about the cost of running Australia.

“I think the answer is a bit of both: It is fearful for some but not for others because it depends on the value of outstanding debt – which of course is mostly housing debt,” Mousina told Stockhead.

“Many Australian households that have taken on large mortgages over the past two years – evidenced by booming house prices – who have fixed at record low interest rates which means they will be rolling over their debt in 2023-24 at much higher variable rates.

“But as an economist, we need to look at the macro perspective so, based on the overall stock of housing debt, we estimate that as interest rates go to 1%, the percentage of housing interest payments as a share of disposable income will rise to ~6% (from 4.4% currently) and this is still manageable.

“When the cash rate rises to 2%, the share of housing interest payments to income will rise to around 7%, back to the average level over 2015-2019 which will provide more of a risk to household spending,” she added.

And that’s where the people who run the economy face a few harder choices.

The expensive brains at Morgan Stanley agree we’re up for our first interest rate rise since 2009 for sure, but while that will totally help ease the volcanic conditions in Australia’s housing market, the fat households savings which we’ve built up during the long-indoor months of the pandemic are a very handy insulator from the baby steps stages of the rising cycle.

Morgan Stanley says house prices are going to unwind and that they expect, “a more pronounced decline to emerge with RBA hikes on the horizon for 2HCY22”.

Any idiot with a mortgage or armed with a deposit can see momentum in the rampant housing market has clearly slowed to start 2022. That’s far from a bad thing, after national housing values jumped 21% last year.

March data suggests this continues to play out – auction clearance rates have fallen below 70% and housing finance data for February shows the value of loan approvals falling ~4%. Sentiment has also softened, particularly amongst owner-occupiers whilst the share of investor activity continues to climb (33.3%), Morgan Stanley notes.

“Supply will both weaken as interest rates are hiked this year, means a softer outlook for housing, and we expect house prices to incrementally decline through 2022, and be 5% lower by the end of the year.”

For one, Eliza Owens, head of Australian research at CoreLogic, said she doesn’t think there’s a heightened risk of first-home buyers defaulting on their mortgage, but added it’s critical the kids understand the risks, particularly regarding the recently announced Federal Budget expansion of the first home buyers’ scheme which targets young people who we all know deserve to vote and own a house and a car, but are generally foolish and don’t get how interest rates work.

“You need to understand interest costs are higher when you take out a low-deposit loan. And that, indeed, those interest costs will be exacerbated as we come into a higher cash rate some time over the next 12 months,” Owens said.

AMP Capital says it won’t be 12 months, it’ll be under two, predicting that the first rate hike will come in June.

“(The RBA) is unlikely to raise rates at its May meeting which will be in the election campaign as wages data won’t be available before that meeting,” observes AMP capital chief economist Shane Oliver.

“This may be a relief to the Government but there will no doubt be lots of talk about rising rates through the election campaign particularly as March quarter inflation data will likely be very high.”

The hawkish pivot in the RBA’s post-meet statement blew a tiny hole through the ASX200 on Tuesday, instigating a fall of about 0.5%, 10 year bond yields rose about six basis points and the Aussie dollar-buck kicked on to its highest level since June last year.

With the RBA getting more hawkish and commodity prices remaining strong, Dr Oliver says the dollar-buck will hit around $US0.80 over the next year.

So – as mentioned at the top – there are about 2.9m Aussie households facing a bump in their record low mortgage repayments. The other third of Australians who’ve payed off their mortgage already don’t care about most of this stuff.

But then there’s the final third of Aussie households who haven’t been invited into this discussion at all.

Nicola Powell runs research and economics for Aussie-listed property platform, Domain, and she says we’ve got a bit of a rental crisis on our hands with already strained rental markets under increased pressure following the reopening of international and domestic borders.

National vacancy rates declined further in March, to their lowest point on record

(Domain)#ausbiz pic.twitter.com/zAYpV6RxcZ

— Pete Wargent (@PeteWargent) April 4, 2022

Last month, Sydney and Melbourne – already under enormous pressure – had the biggest monthly tightening in vacancy rates nationwide; vacancies are now at 1.4% and 1.8% respectively.

Samuel Theo, principal of Sydney’s inner-city realtor Sublime Property, told Stockhead while the impending rate rises would absolutely help subdue house prices, the inverse would be true for rental markets.

“As the cash rate climbs, we expect an already tough rental market to feel the pressure.

“House sales will diminish as volumes tighten – homeowners choosing to delay putting their house on the market, and this will have a flow through effect on rents… when the cost of a mortgage goes up – like when the price of anything goes up – demand falls. And if less houses are on the market, then less stock is available for a very large pool of renters, especially here in the inner city markets.”

Dr Powell agrees.

“With many cities already sitting at record high asking rents, combined with the current tightening conditions, we’re likely to see rental price increases continue, causing worsened conditions for tenants,” she said.

“In some of our cities it is like finding a needle in a haystack when trying to find an available rental.”