Peak Inflation: Are we there yet, Diana?

Diana Mousina, AMP Capital

Technically, it’s never a bad time not to be in the UK, but with the investment genii at Goldman Sachs now warning English inflation could top 22% some time in 2023, there’s never been a better time to be elsewhere.

With wholesale energy prices across the UK and Europe going bonkers, Goldman economists reckon headline inflation in the UK could peak at 22.4%, and that British households might even see the Ofgem energy price cap for households leaping over 80% by January next year.

Last week Britain’s independent energy regulator announced the energy price cap will increase to £3,549 per year for an average household from the 1st of October.

This comes as energy prices over there have spiked 145% since July and Ofgem’s CEO warned of the hardship energy prices will cause across the UK in the coming winter and urged the incoming Prime Minister to provide an additional and urgent response to the surging energy prices.

The increase reflects the continued rise in global wholesale gas prices, which began to surge as the world unlocked from the COVID-pandemic and have been driven still higher to record levels by Russia slowly switching off gas supplies to Europe.

Goldman’s forecast easily eclipses a cavalcade of grim predictions. Citi bank pegged UK inflation for an 18.6% peak next year, while The Bank of England with skin in the game and a lot on its shoulders forecast a peak above 13%.

What’s worse, it’s always raining in England.

Diana Mousina, senior economist at AMP, told Stockhead those gorgeous, fluttering, wholly-devoured early signals that we might be nearing peak inflation (yes, the ones which implied central banks would start easing up on the rate hikes and led to that initial post-low June rebound across global equity markets) may’ve been a wee bit misconstrued.

Waters muddied, signals sullied

Traders certainly took the bait. The S&P 500’s closing low this year came ahead of the feel-good. On June 16 the index struck 3,666.77, taking the broadest US index some 24% off the all-time highs it was hitting in ’21. It’s reclaimed about 14% since then, although those gains now appear to be more borrowed than owned.

“Central banks have been cautious to confirm a “pivot” from an aggressive rate hiking cycle – as we saw with Fed Chair Powell’s speech at the Jackson Hole central bank symposium – as it’s looking more and more unclear when inflation will slow and by how much,” Diana said.

The latest inflation indicators, by the book

There’s a bunch of them, probably not enough here in Australia, but the latest leading inflation indicators have given off a few flashing beeps and buzzes that global inflation will slow from here.

b:

1. A fall in goods spending after the Covid-surge in 2020/21. This, she says, is helping to ease supply chains.

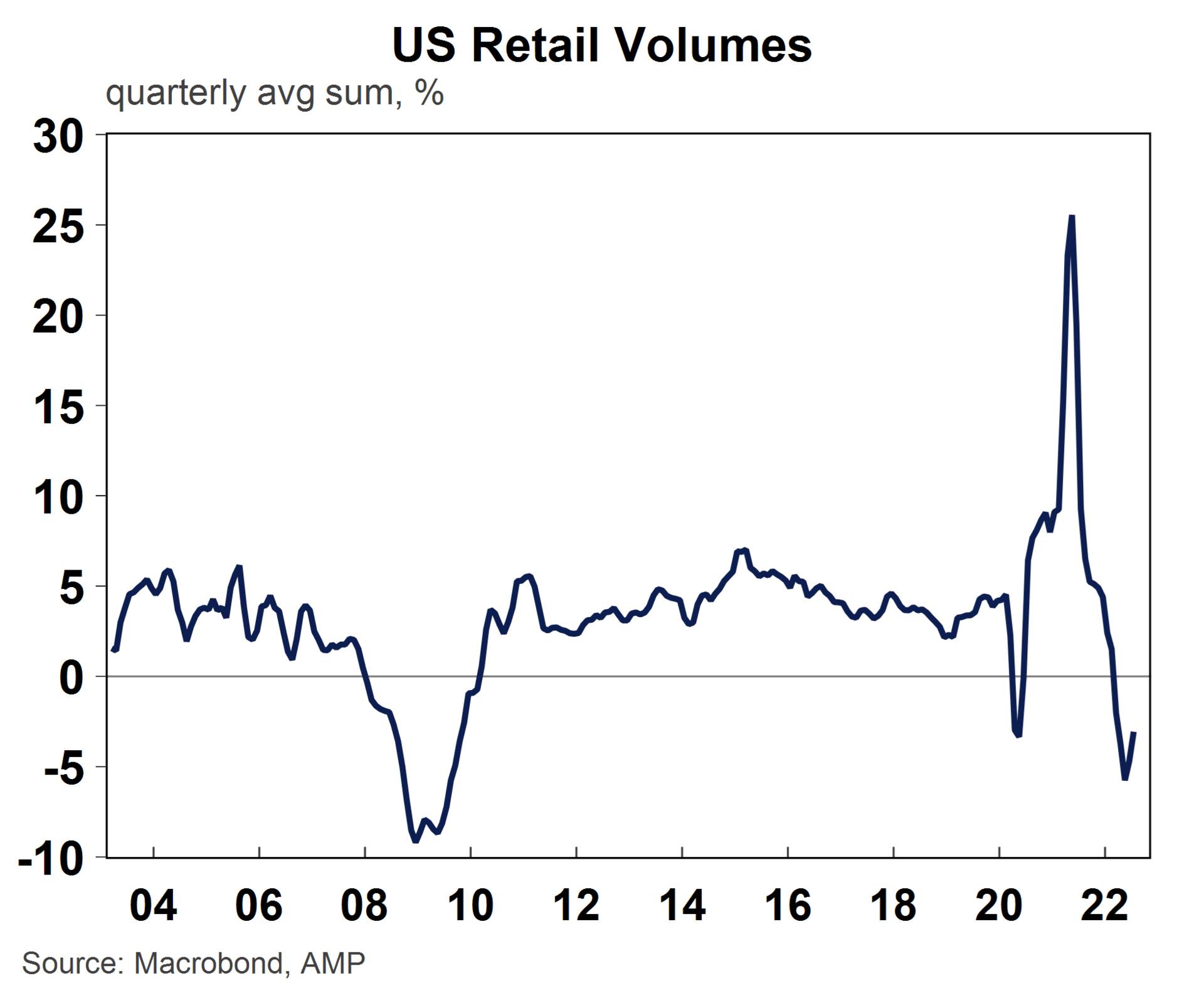

2. US retail sales volumes are down by 3% over the year to July (on a quarterly basis).

3. Australian retail spending was weak in June but kicked some butt in July, so that too is yet to show signs of significant slowing.

4. An improvement in supply chain issues caused by COVID-19.

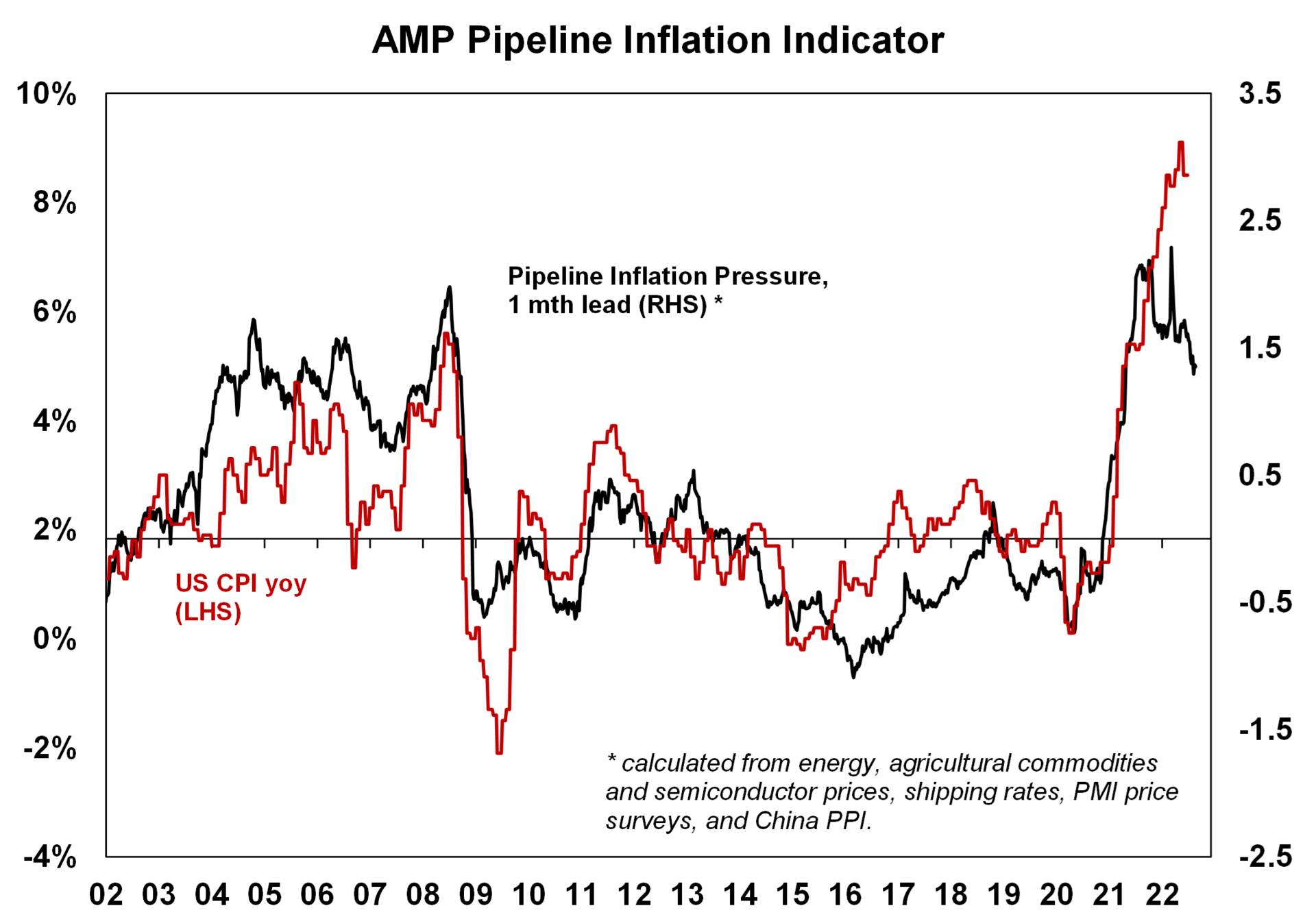

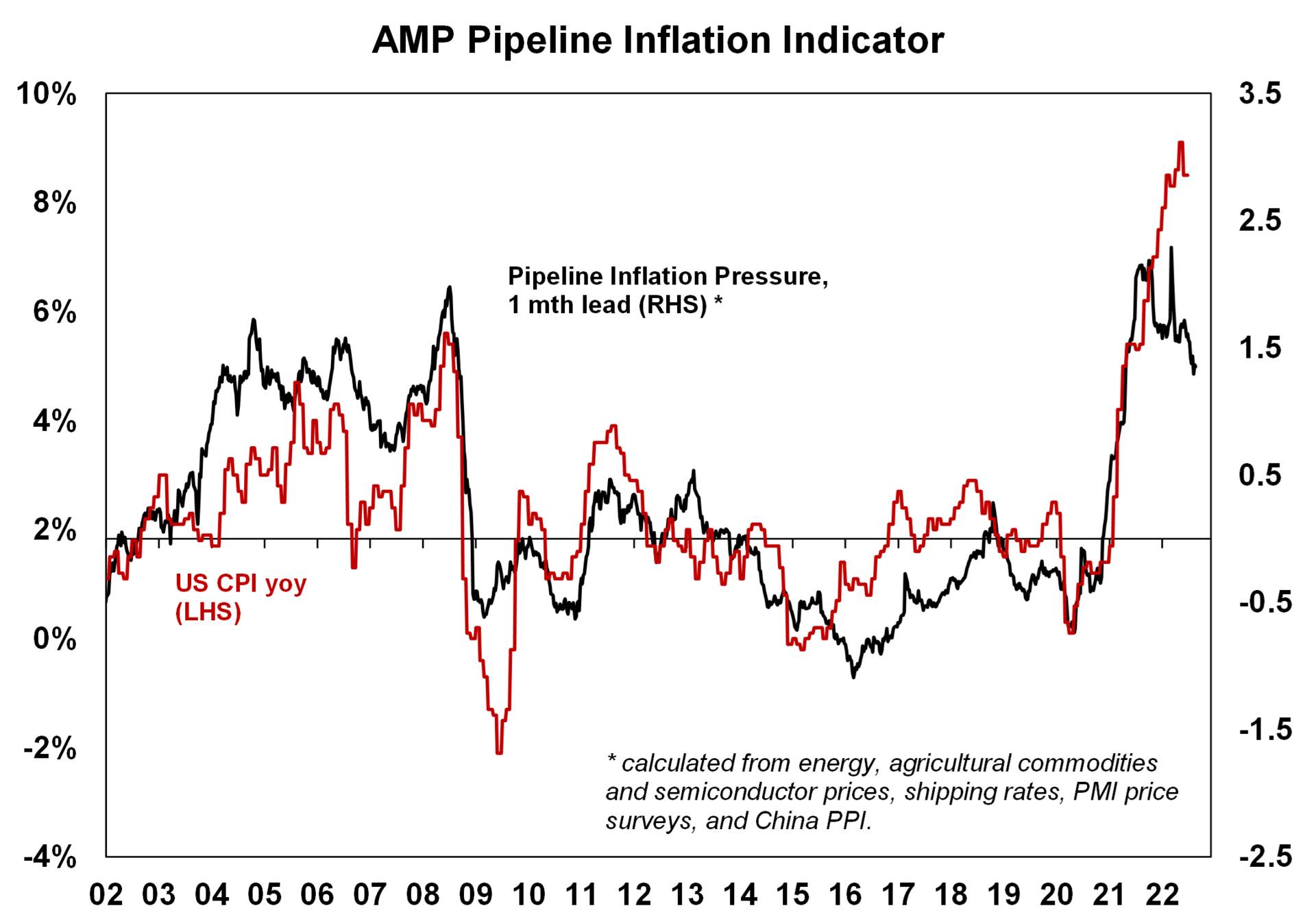

“There’s data now which shows delivery times, shipping rates and semiconductor prices are all improving and well down from early 2022 highs (although, no, still not back to the pre-2020 levels).

“This has happened as consumer goods demand has slowed, global travel has rebounded and employee absenteeism or, as you say Christian – skiving – because of COVID-related illness or whatever has clearly improved… and… then you’ll put the charts in?,” she said, sounding uncertain.

To which I answered… maybe.

(Ed: He did. Here they are below. We’re so sorry Diana. Everyone. )

“A decline in commodities prices from their highs, with declines in agricultural prices (like wheat, grain, cotton and soybeans), oil and metals (like aluminium, copper and silver).”

However, Diana says non-oil energy prices continue to rise, especially in Europe.

Europe and the UK are right in the maelstrom, that’s for sure

Europe is in the crosshairs this week – not only vis a vis inflation and next week’s ECB meeting, but also the brains trust trying to figure out how to break the link between the price of gas and the price of electricity. A subsidy, which is their solution for everything, is not the best choice inflation-wise although several European members have already done that, too.

The Euro Commish told the Financial Times that they’re “working ‘flat out’” but then they announce an “emergency” meeting of energy ministers a decade away on Sept 9.

I mean.

Come on Europe.

Anyway, the EU Commish has previously said despite more cuts to gas supply by Russia’s Gazprom, the situation they reckon isn’t so bad is to turn the previously agreed voluntary 15% reduction in gas use to a mandatory 15% cut in gas use.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

But – and there’s always one – Diana says there are also opposing forces that are well capable of keeping inflation higher for longer:

You can bet someone else’s house that rental inflation will rise further

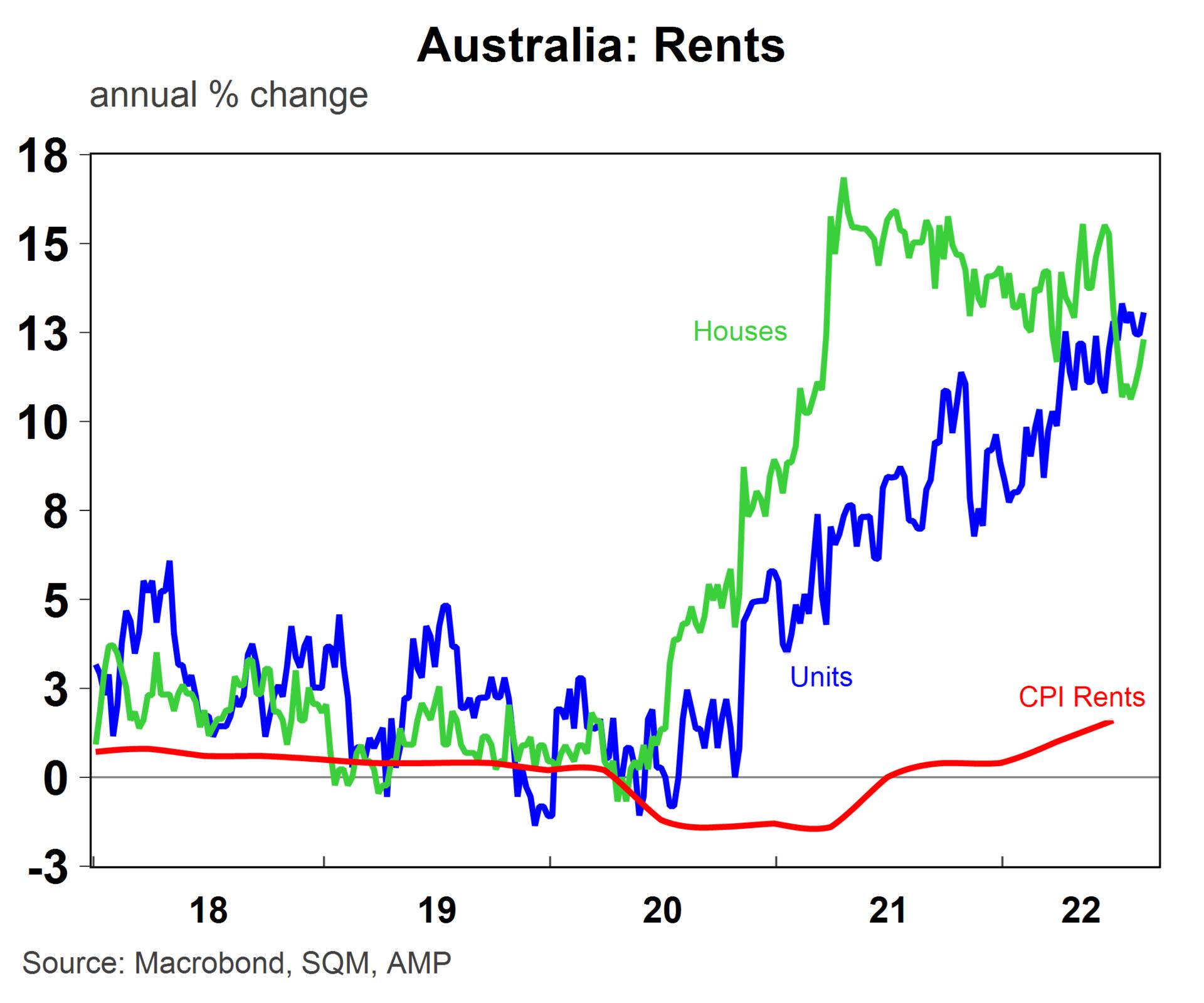

“Australian rents in the consumer price data are up by 1.6% over the year while asking rents (which represent newly negotiated agreements) are up around 13% year on year for units and 12% for houses. (Ed: better see the chart below) with the big difference between the two reflecting historical rental lease agreements which still need to be renegotiated.”

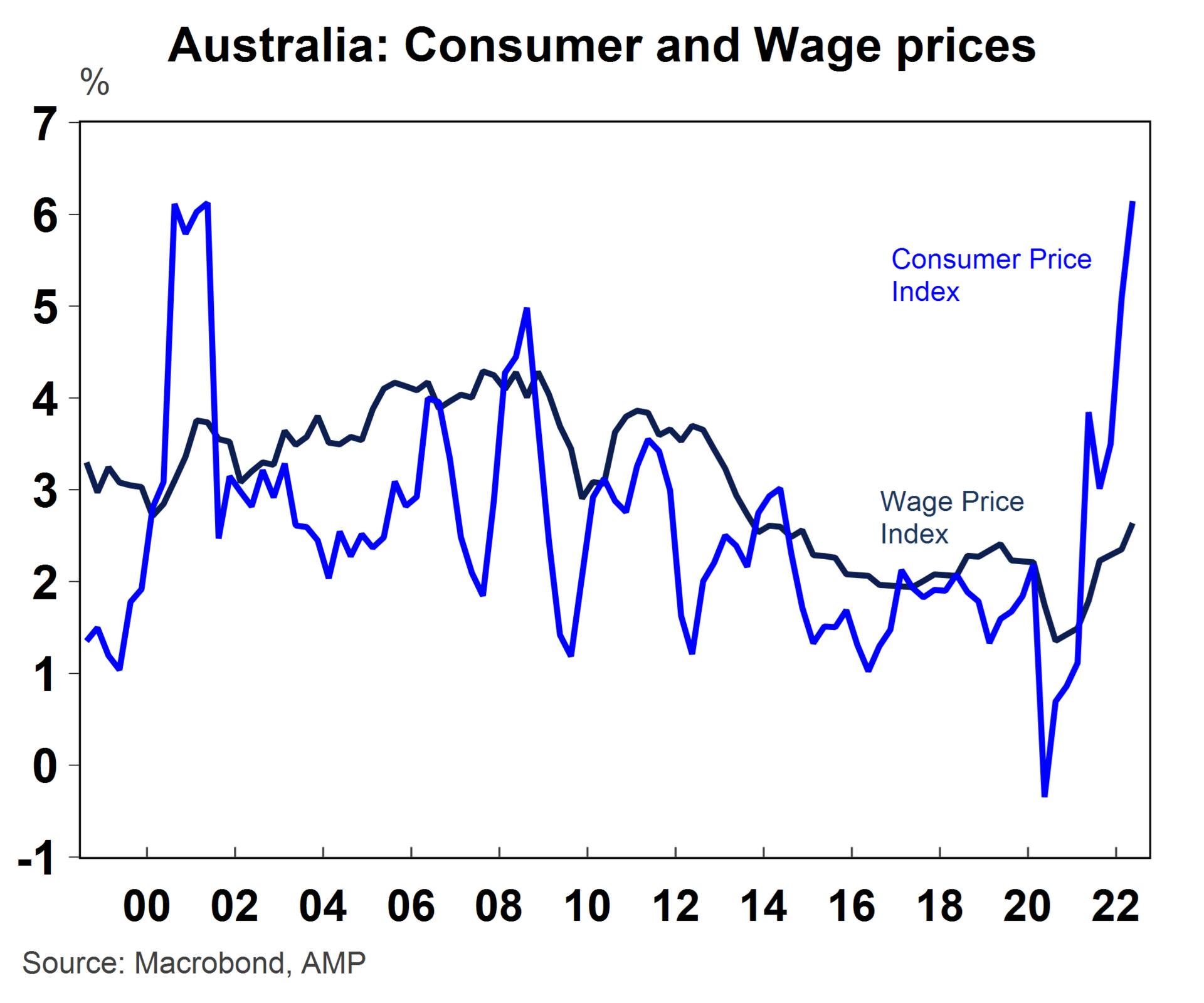

“Wages growth will rise further in Australia which could drive inflation higher as staff costs tend to be around 70% of business costs,” Diana warns.

“In the states, the average hourly earnings are running at between 5-7% year on year on various wage trackers, while Australian wages growth was at 2.6% over the year to June and we expect a peak at 3.75% in 2023.”

It’s the breadth that worries

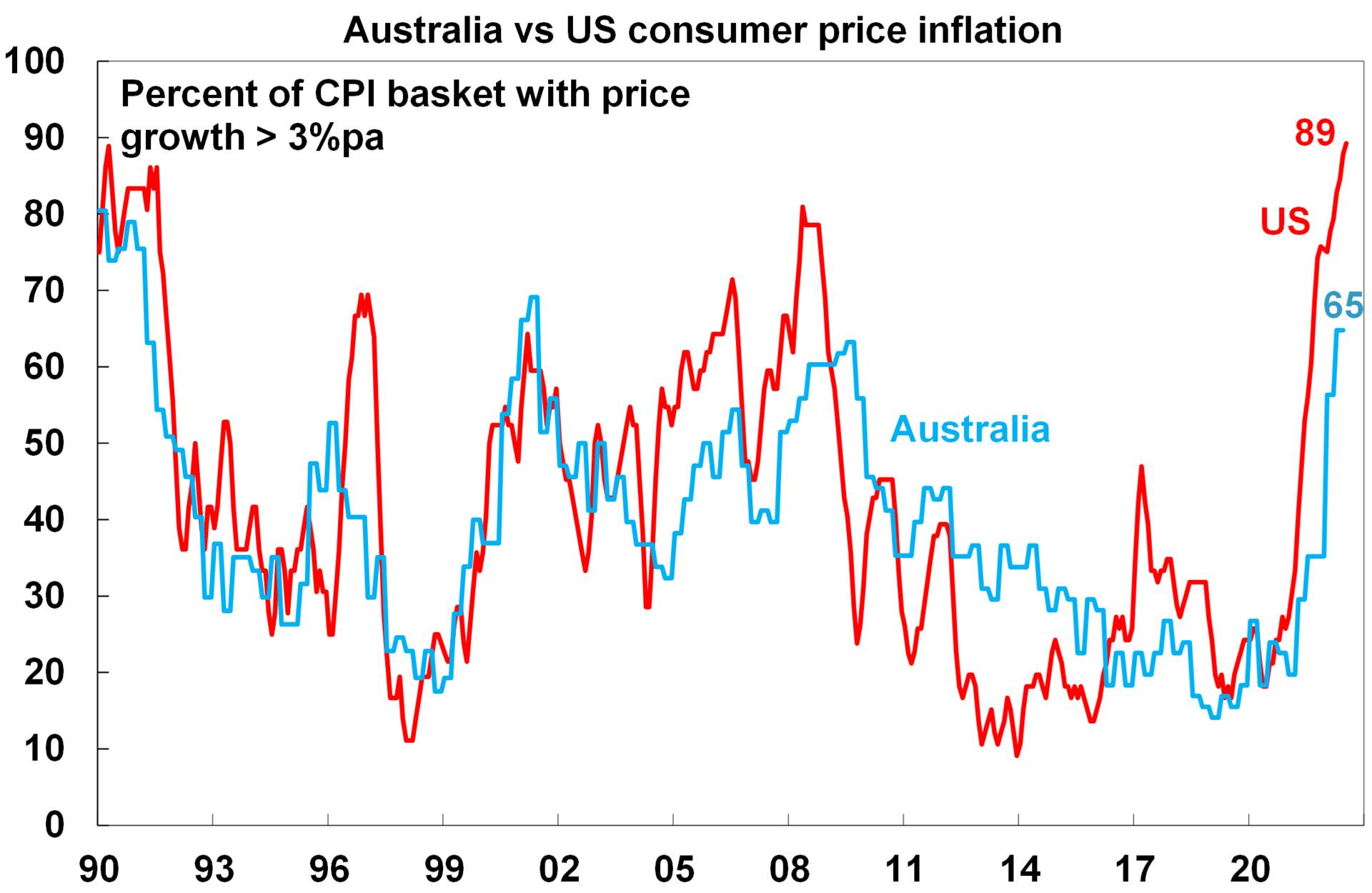

“The breadth of large increases in prices is high, with 89% of components in the US CPI basket seeing a 3% increase in prices over the year to July and 65% of Australian components having a 3% year on year increase as at June.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

European energy prices remain stubbornly high and continue to increase (European gas prices are up by 160% since June while US gas prices are just slightly up on their June highs) which will cause a higher and later peak in European inflation.

The outlook

Diana says:

In the short-term, inflation is expected to decline relatively easily in the US as the contribution from falling commodity prices will more than offset some of the broader high inflation pressure (like wages and rents). However, the risk is that some of those longer-run inflation drivers end up lifting inflation later on (which already looks to have started). So, the US consumer price index is likely to end the year around 6-7% per annum (well down from a peak of 9.1% in June). But, consumer price inflation is very unlikely to get back to 2-3% quickly in 2023 and is likely to remain sticky around 3-4% in 2023 as some of the longer-run inflation pressures keep price growth elevated. This means that futher rate hikes should be expected.

A pick up in domestic inflation has lagged the rest of the developed world, so the peak in inflation will also come later. We expect headline consumer price inflation to peak around 7.5% by December 2022, 5.5% by mid-23 and 3.5% by late 2023. Relatively lower wages growth in Australia compared to global counterparts means that there is less flow through from wages growth to inflation.

Inflation in Europe may not peak until early 2023, when energy prices start to decline which will result in a challenging economic environment for Europe over 2022/23.

Implications for central banks

While headline inflation may decline (in year on year terms) over coming months, price growth is likely to remain above inflation targets in 2023, so central banks will continue raising rates into next year (although probably not at the same pace as recently), keeping downward pressure on economic growth and corporate earnings.

In the near-term this means more downside risk to shares, until it is clear that central banks will start to ease up on rate hikes.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.