The White House: Why the bears love salmon

Via Getty

In this series, global equities portfolio manager James White ditches micro and macro and embraces “The Meta” perspective. A place where James can obsess over the detritus of where economies crash into equities.

Whitey’s house is Lessep IM, a Sydney-based global equities investment manager with this terrifying belief at its core:

Today the global economy is at the height of a productivity expansion equivalent to the fiscal, social and industrial evolutionary spike of the late 19th century. This period, driven by technological change, brought rising living standards, deflationary pressures, turmoil in asset prices and general carnage and upheaval.

We invest in global equities. We run a core portfolio of 40-50 stocks that capture the opportunities in productivity trends. These trends reflect investments in the drivers of productivity and the beneficiaries of productivity. We also aim to run a long-tail of stocks that have the potential to capture a greater share of new or existing markets.

James said this once, to someone: “I love trying to explain the world and equities offers the opportunity to do that in a meaningful way with a scoreboard attached.”

That’s nice.

Here’s his pic, it’s always nice to know who’s talking.

For Australians of a certain age, salmon came in a tin, branded John West, the inventor of funny internet commercials.

T’was wan-ish and pale pink in colour, brined in only the yeastiest of salt water, the slipperiest oily skin, and with brittle, yet razor white bones to crunch on.

It wasn’t much of a treat, mum. No it wasn’t.

For today’s pale-limbed, screen-spoilt mumbling Australian children, and perhaps many others around the world, salmon is a lithe orange, a little unctuous, raw, possibly still twitching and often wrapped around a ball of the finest rice.

It might now be considered a staple of childhood diets.

Salmon demand

And it’s not just Australians and their children. Indeed, according to Chef’s Pencil (thanks guys, here’s the full report), sushi has adherents all over the world; those in Ukraine and Russia are amongst the biggest. The rankings below are based on Google trends analysis.

Global farmed fish consumption has grown 7% per annum from 1960 to over 100 million tons. Fish is considered a healthy protein that is enjoying demand growth as urban middle classes expand, around the world. Mowi, the largest salmon farmer in the world, calls it the food icon of the 21st century.

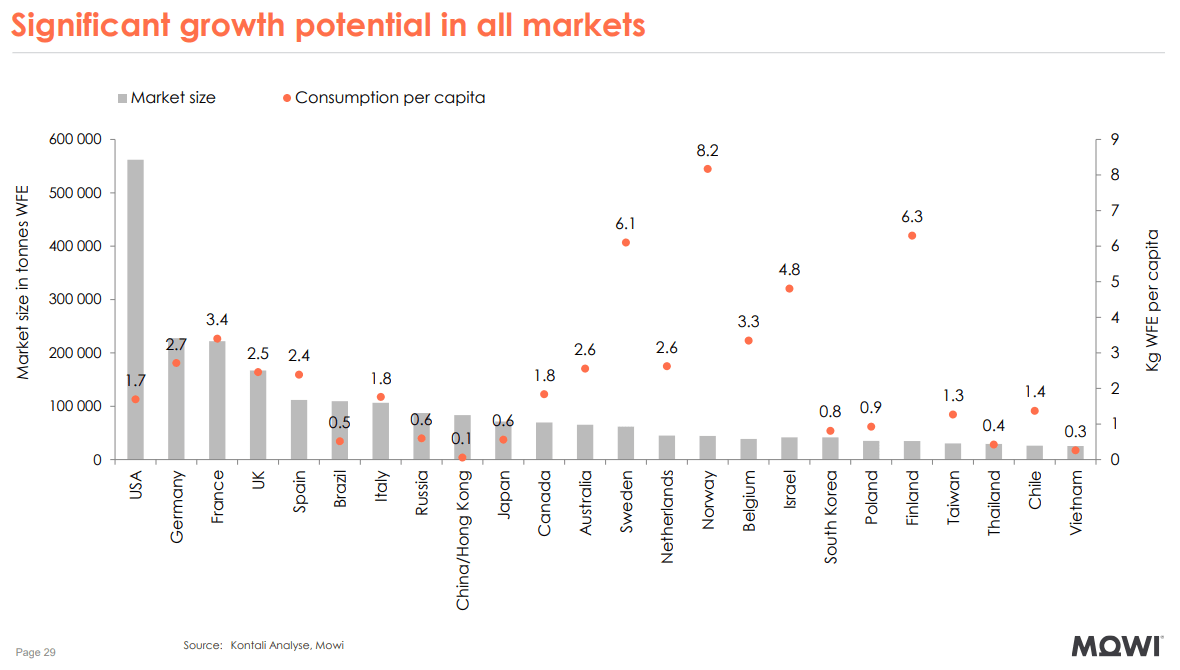

Mowi’s chart below shows the potential for consumption growth to maintain 7% per annum for some time as large markets grow per capita consumption.

Salmon supply

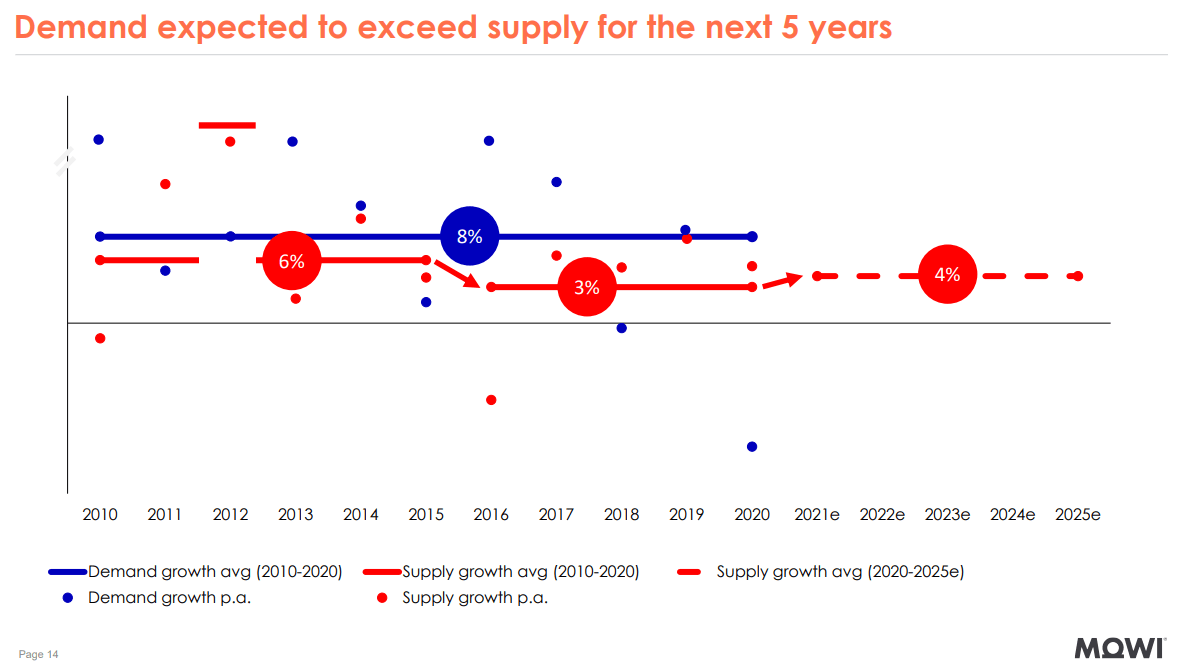

The supply of salmon is a little more problematic. As the chart below shows, demand has out-stripped supply growth over the last decade. This is likely to remain the case for the next five years. It has, historically, been difficult to increase the supply of farmed salmon. There have been a number of reasons for this.

First, salmon need very cold water.

This means geographically it is limited to areas above (in the north) and below (in the south) 45 degrees: Chile, New Zealand, Tasmania, in the South, and Norway, Iceland, Scotland, the Faeroe Islands, and Canada, in the North. Also Canberra if it had a soul (or a real lake).

A solution, when natural gas was cheap, was to farm fish in Florida, using salt water from an aquifer near Miami. Other solutions include using scrapped oil tankers.

Second, it’s dirty.

Salmon pens create waste, making it difficult for new salmon farms to receive approval in areas without historic salmon farming. Typically, waste products from sheltered fish farms will settle on the sea floor and may cause algae blooms.

Part of the solution is offshore, or exposed, fish farms where waste can be taken out to sea by currents. Again, however, these solutions are more expensive. There is a higher probability of loss and danger to other sea life. Open water salmon pens are often made of Kevlar fibres to stop sea life hurting themselves when attacking the pen.

Finally, aquaculture is plagued by disease. For instance, the decline in average supply growth between 2016 and 2019 was in part driven by a breakout of sea lice in the farming populations of Chile.

The Investment Opportunity

The combination of constrained supply and strong demand growth make an investment in the salmon industry attractive.

Further, it’s a good economy reopening play. Sushi is best at a restaurant.

The challenge for Australian investors has been managing geographic risk. For global investors, however, the Norwegian salmon farmers provide substantial operational, and geographic diversification.

Further, the scale of the Norwegian producers mean they can take advantage of supply disruptions elsewhere.

Typically, the Lessep portfolio would hold around 4% in a basket of Norwegian producers including Mowi, Norwegian Royal Salmon, Salmar, Grieg Seafood, and Leroy.

The current mid-20s PE ratio belies a rapid improvement in annual earnings as restaurant demand rises post-pandemic. Norwegian Royal Salmon, for instance, farmed 7% less in Q1 2022 than Q1 2021 due to a disease problem in its fish but doubled EBITDA on higher realised prices.

The sector is likely to enjoy EPS growth through to 2023.

At home: the listed Aussie aquafarmers

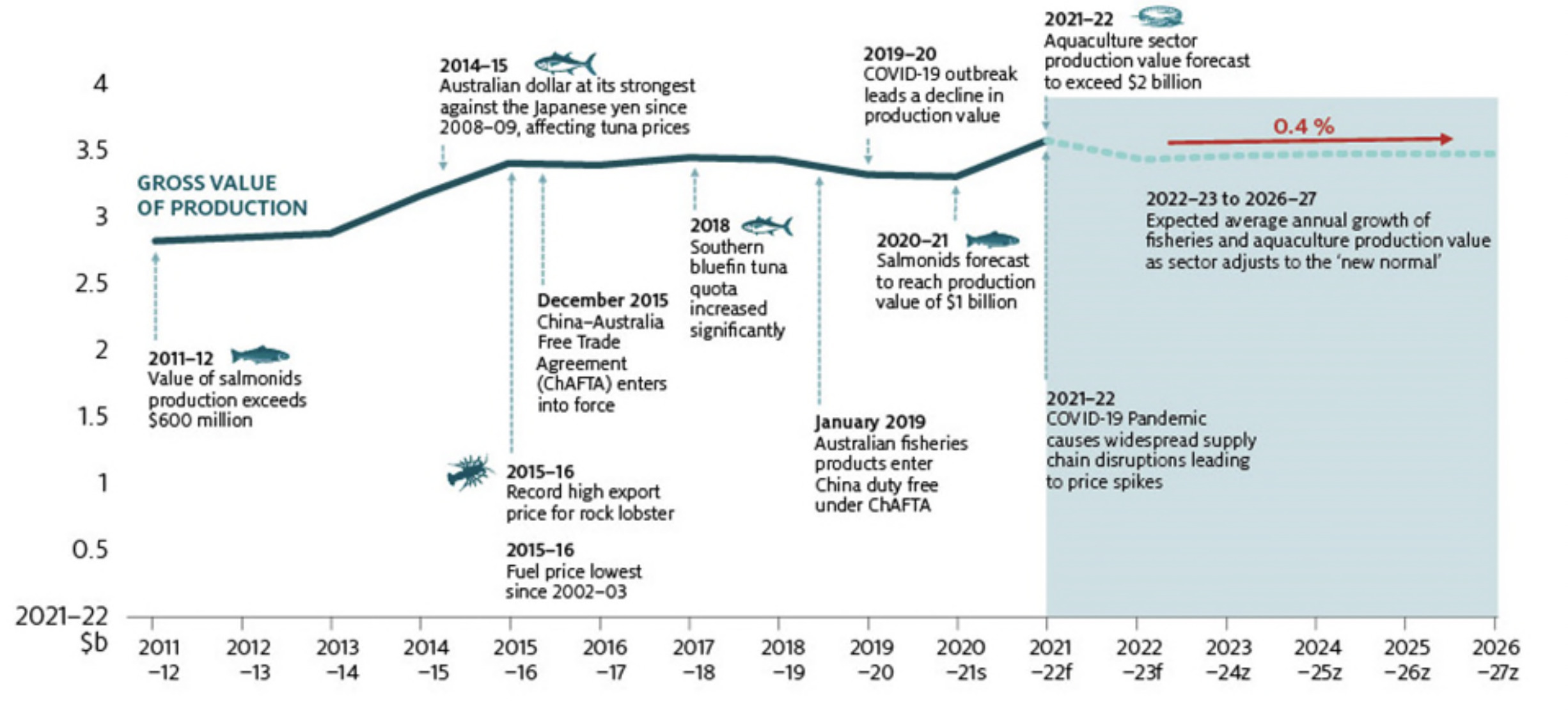

The Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), says the Aussie fisheries and aquaculture production value is forecast to rise by 10% this fiscal year.

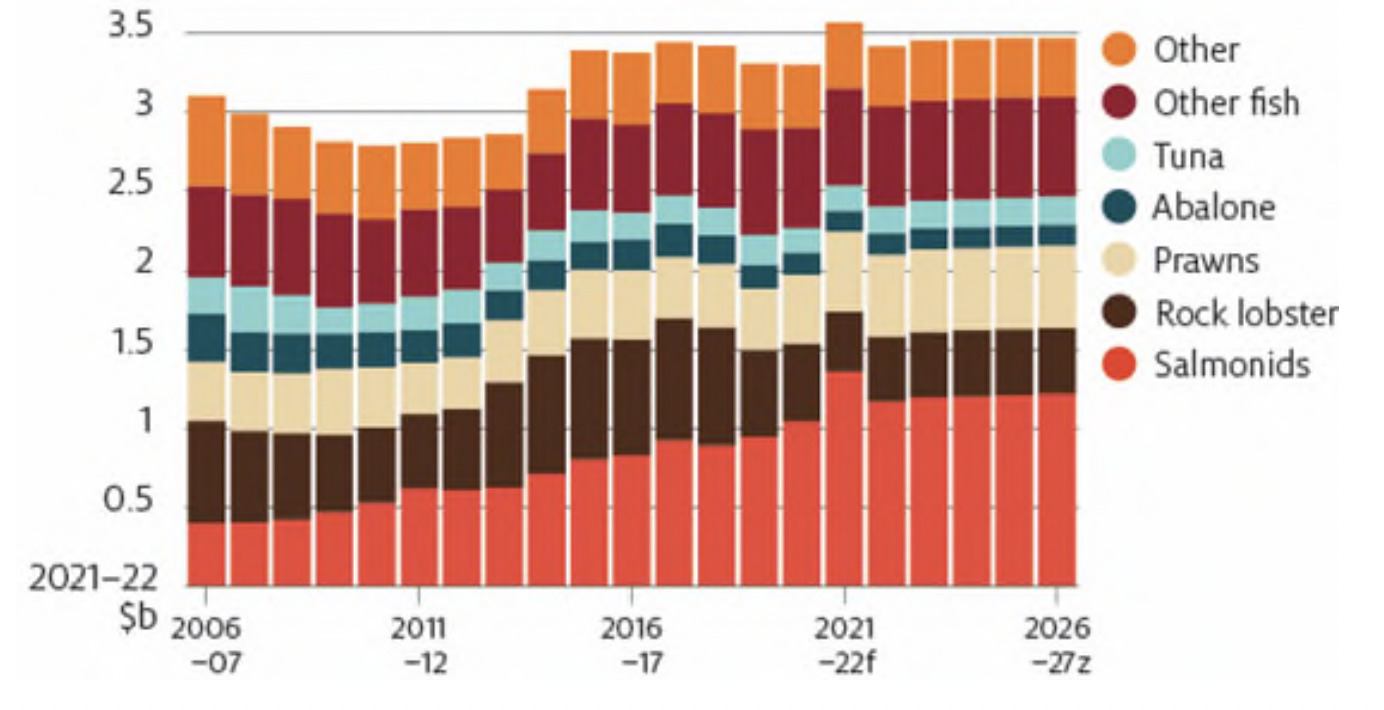

The strong growth in production value follows higher prices for ‘salmonids, prawns and oysters.’

It also comes lock-step with a time of rising domestic and international market conditions for these fishy products, as restrictions on people movement ease after the COVID-19 lockdowns.

ABARES expects salmonid prices to decline in next year though. Over the medium term (2022–23 to 2026–27) the total value of fisheries and aquaculture products is projected to return to trend.

New Zealand King Salmon (ASX:NZK) is always up there finding salmon of the royal variety.

Last month, NZK, one of the world’s largest king salmon producers, raised NZ$50.3 million (A$45.75 million) through a rights offer to repay debt and fund operations for the next fiscal.

Murray Cod Australia (ASX:MCA) is likewise a fish breeder and exporter and has had a turbulent run.

The company’s lows include a pond failure in 2017 while also having to assure investors in 2019 that it didn’t source fish from the Darling River.

But its highs include a partnership with celebrity chef Heston Blumenthal and turning losses into profits from FY20 to FY21.

2006–07 to 2026–27: ABARES

Huon (ASX:HUO) was acquired for $425 million by Brazilian meat giant JBS – after seeing off a competing bid from iron ore magnate Andrew Forrest, is a sector giant, the local Krahen, while fellow Tasmanian producer Tassal (ASX:TGR) is also high on the hit list of Investors Mutual portfolio manager Marc Whittaker.

Sadly, the great dream of Seafarms (ASX:SFG) — to build a massive prawn farm (Project SeaDragon) at the Top End, may be dead in the water. But, still. Watch the vid!

The views, information, or opinions expressed in the interview in this article are solely those of the writer and do not represent the views of Stockhead.

Stockhead has not provided, endorsed or otherwise assumed responsibility for any financial product advice contained in this article.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.