- Experts say green investment will need to triple to hit 2050 target

- RBA’s Carl Schwartz explains how Australia will play a part

- We look at the predictions for green bonds and ethical funds

Climate scientists warn that carbon emissions are heating the planet, and that the rise in temperatures is already having immediate effects on our weather patterns.

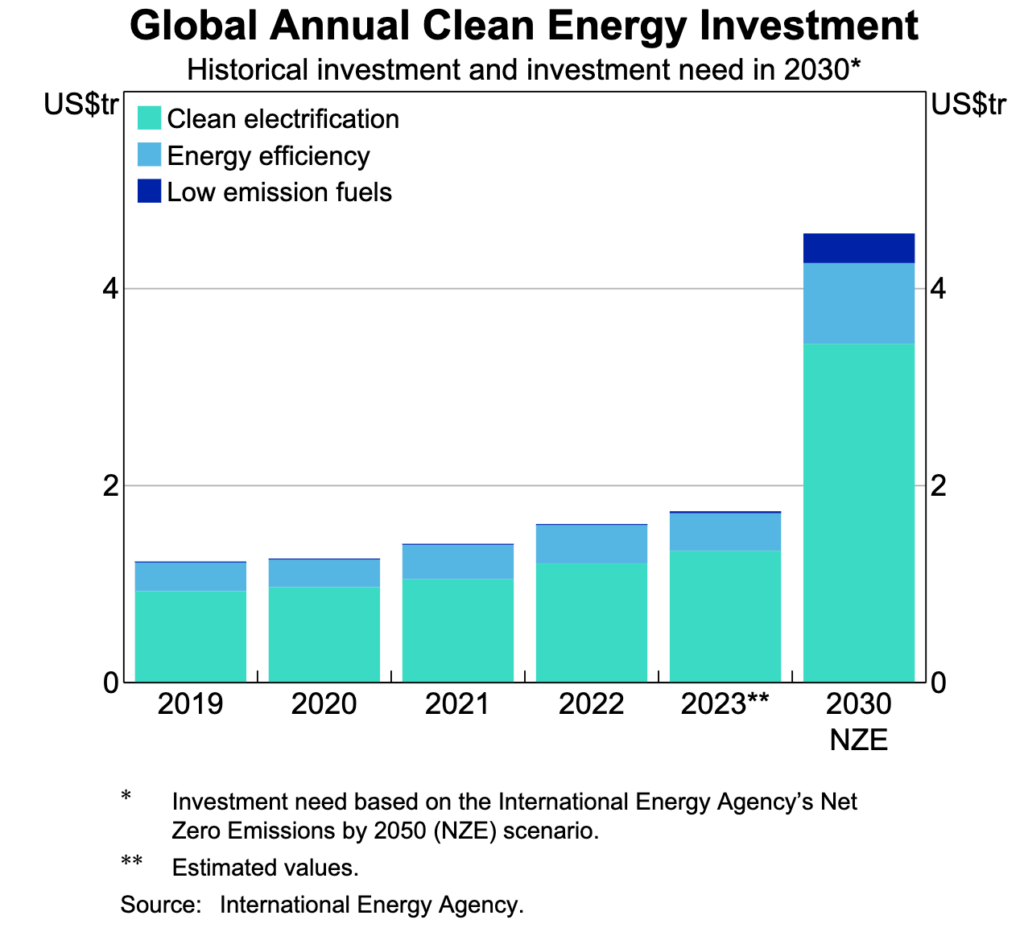

World leaders agree that emissions must be reduced, and that by 2030, annual investment for clean energy alone will have to be running at around three times the current pace.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) also said this pace would need to be maintained through to 2050 to meet the net zero commitment.

Carl Schwartz, Acting Head of the Reserve Bank’s Domestic Markets, believes Australia will play a big part in the years ahead, noting that we’ve already committed to meet a target of net zero by 2050.

“We currently have carbon-intensive electricity generation,” Schwartz told the audience at the Risk Australia 2023 Conference on Tuesday.

“But we also have large natural endowments that can help facilitate the transition ahead. This includes wind and solar renewable energy – where investment has already grown strongly in recent years.”

How Australia will play a part in the transition

The transition towards a green world presents both risks and opportunities, and investors would want to be on the right side of this equation.

In Australia, there’s been a remarkable growth in green and sustainable financing markets over the past few years.

Experts now expect this growth – especially the green financing market – will explode over the next few years.

There are four areas of financial markets that could see significant growth in Australia – green bonds, green loans, green securitisations and ethical funds.

Green bonds

The Australian green bond market has grown quickly since its inception in 2014, though it remains a modest share of the overall bond market.

Broadly speaking, green bonds are bonds issued to fund projects that are beneficial to the environment or climate.

Some examples include clean transportation projects, energy efficiency projects, and green construction and/or green modifications to buildings – in fact, these have been the main uses of green bonds in Australia.

For classification as ‘green’, issuers and investors have tended to rely on voluntary guidelines developed by various international not-for-profit organisations.

Schwartz says that evidence from international markets suggest that green bonds can attract investors at lower yields (higher prices) than their non-green counterparts – a so-called ‘greenium’.

“Previous research has explained this as reflecting investor preference for socially responsible investments,” he said.

Green loans

Green loans are offered by some Australian banks and non-bank lenders for finance for a range of products, including residential property, automobiles, and ‘personal’ expenditure.

Though data is hard to come by, numerous reports suggest that activity in green loans is gaining considerable momentum.

“To receive a green loan, the asset to be funded must meet eligibility criteria to show it is contributing to an environmental objective,” said Schwartz.

As with green bonds, however, there is currently no centrally administered definition for what constitutes a ‘green loan’ in Australia.

According to Schwartz, green loans are an attractive prospect for assisting in the green transition.

“Given the size of household lending and residential emissions – residential buildings contribute more than 10 per cent of Australia’s carbon emissions – there is considerable potential to make a meaningful reduction to overall emissions.”

Green securitisations

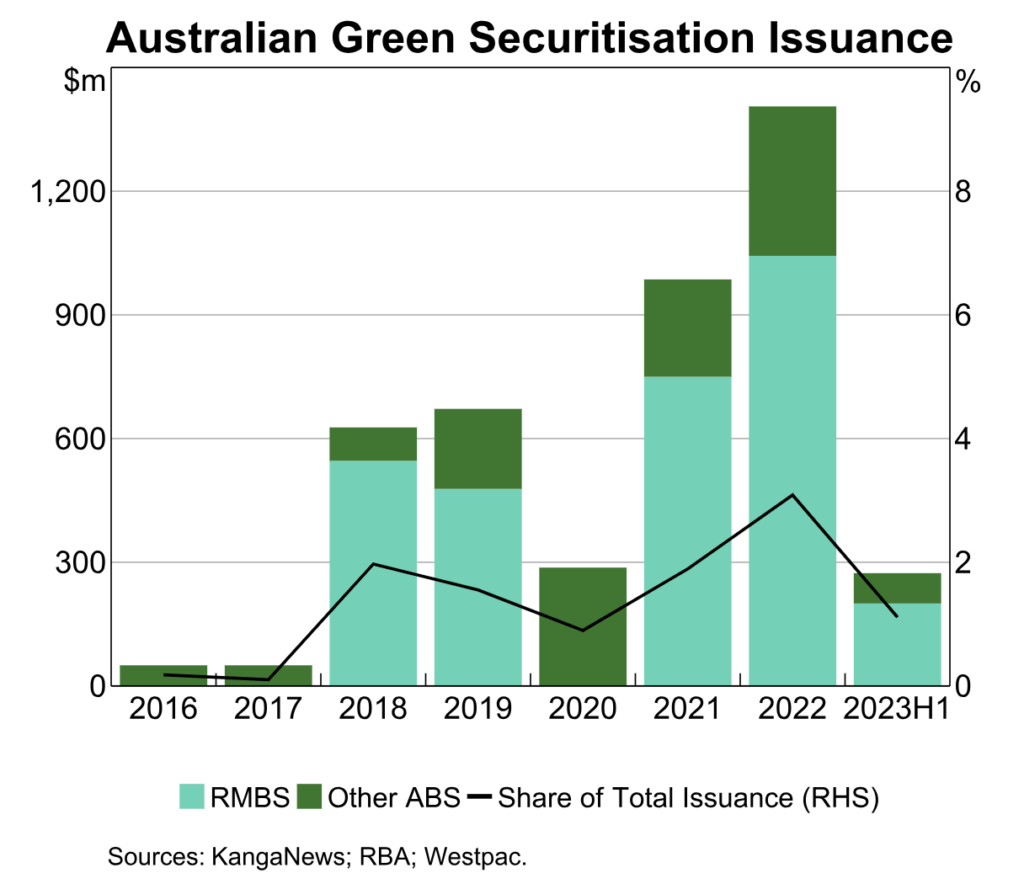

Green loans are the collateral for green asset-backed securities (ABS) – or ‘green securitisations’.

Issuance in the green ABS market has followed a similar trajectory to green bonds, albeit on a smaller scale. Volumes have grown following the first green ABS issuance in 2016, hitting a record $1.4 billion in 2022.

That said, volumes have slowed a little in 2023 to date. As a proportion of total issuance, green securitisations have also grown but remain quite low.

Ethical funds

In the equities market, there is no equivalent concept to green bonds and loans because an equity is a share of a company, which may engage in both green and other activities.

These managed funds may advertise a broad ethical mandate, which usually incorporates green aims and investment strategies.

“Ethical funds primarily invest in equities, but they also maintain smaller investments in fixed-income, property and alternative assets,” said Schwartz.

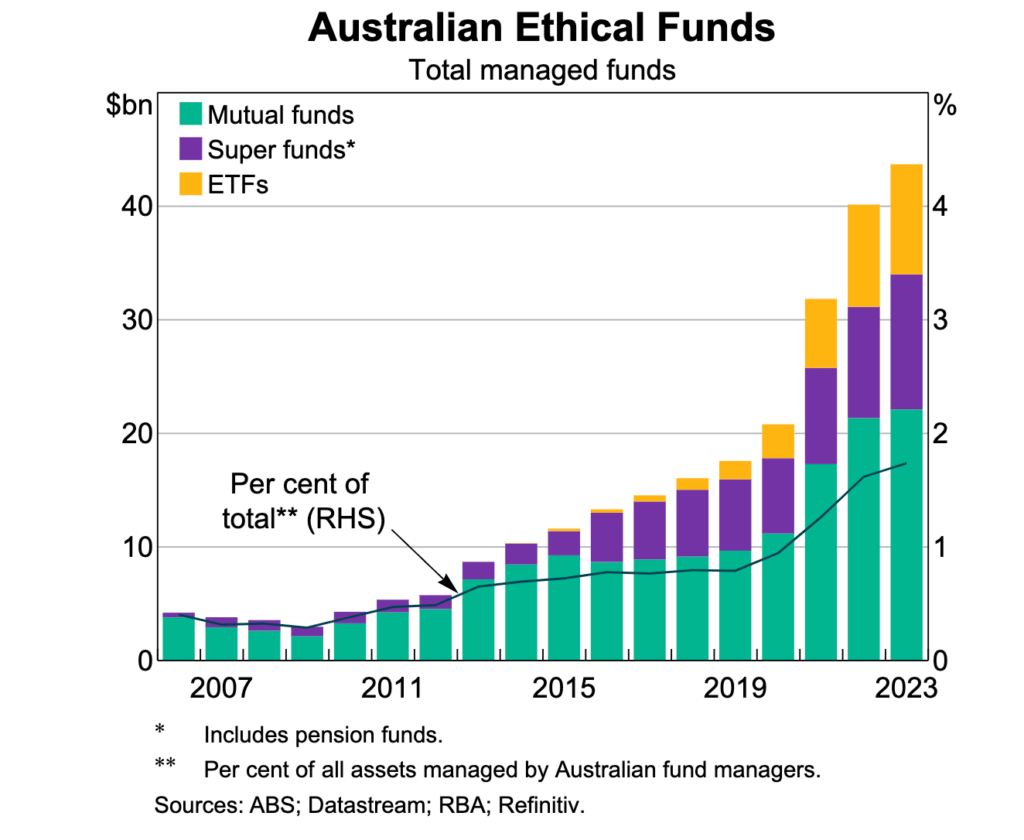

By this definition, ethical funds first appeared in Australia in the 1980s, but growth has been picking up of late.

“In the past five years, the number of new ethical funds being launched has doubled relative to the previous five years,” Schwartz said.

ETFs also emerged in the past decade, and since 2008, ethical funds have grown significantly both in dollar terms (to around $45 billion) and as a share of total managed funds, though this share remains modest at less than 2%.

So what’s ahead for Australia?

Schwartz believes these developments are a positive sign that issuers and investors alike are embracing green and sustainable finance in Australia.

That said, financing for sustainable activities will need to increase substantially in the period ahead if we are to decarbonise and meet net zero goals.

“Recognising this, there are various activities underway to further develop Australia’s sustainable finance framework,” explained Schwartz.

“Many of these measures focus on supporting the quality and consistency of sustainability-related information.”

Schwartz added that the Australian Government has proposed mandatory climate-related financial disclosures for large businesses and financial institutions, with the aim of promoting greater transparency.

“The Australian Government will also support the development of an Australian sustainable finance taxonomy,” said Schwartz.

Separately, the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) is also doing its part and actively working against ‘greenwashing’.

“ASIC is addressing this by promoting awareness of the regulatory expectations, undertaking surveillance and, where necessary, taking action to enforce standards,” Schwartz said.

Meanwhile, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is seeking to ensure that APRA-regulated institutions manage the risks and opportunities that arise from a changing climate.

“And for our part, the Reserve Bank is closely following these developments and contributing through our role on the Council of Financial Regulators Working Group on Climate Change.

“We continue to increase our understanding of the implications of climate change for the Australian economy and financial system, via internal analysis and external engagement.

“We are also committed to improving the environmental performance of our own operations,” said Schwartz.

Taken from a speech by Carl Schwartz, Acting Head of the Reserve Bank’s Domestic Markets, to the Risk Australia 2023 Conference on Tuesday August 8, in Sydney.

Read MoreESG