‘Very, very profitable’: Nigel Ferguson on AVZ’s plans for lithium world domination

Pic: John W Banagan / Stone via Getty Images

Like many ASX lithium stocks, AVZ Minerals (ASX:AVZ) is having an incredible year.

The difference is that AVZ, unlike many lithium stocks, has been plugging away at its world class Manono lithium-tin project in the Democratic Republic of Congo since 2016 and now – in 2021 – is almost ready to pull the trigger on development.

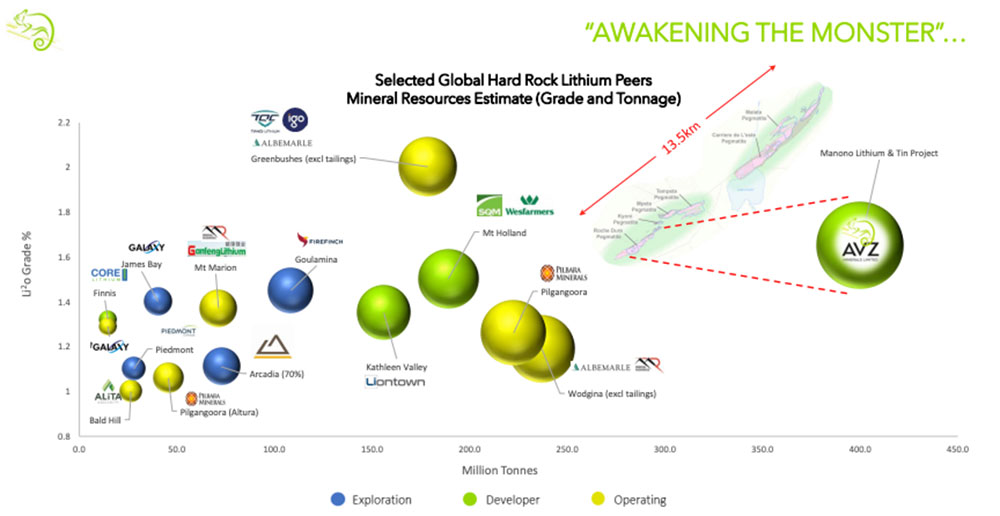

Manono is a standout project. According to the company, it is:

- the biggest undeveloped deposit in the world

- the second highest grade undeveloped deposit in the world

- in the bottom cost quartile for production globally, and

- in the bottom quartile for greenhouse gas emissions

… and that’s just based on 10% of the mineralised strike. As managing director Nigel Ferguson says – “very, very profitable”.

Over the past year or so it has inked long-term, binding sales agreements with three major Chinese lithium converters for 80% of its 6% Li2O spodumene concentrate.

It has also brought on cornerstone investor CATH Energy Technologies, who will shell out $US240 million for a 24% direct interest, plus another ~$160m to get the ~$US540m project into development. The ducks are lining up.

We talk to Ferguson about AVZ’s plans for world domination.

How does the Manono compare to other lithium mines or near-term development projects?

“It is the largest, second highest grade undeveloped deposit in the world. We will be in the bottom cost quartile for production. We are also in the bottom quartile for greenhouse gas emissions,” Ferguson says.

“There are five major pegmatites at Manono, and we have only drilled out ‘Roche Dure’, or 10% of the total strike length.

“We have spent about $US67m on the project so far. Drilled just under 30,000m; about 27,500m of that at Roche Dure which now has a resource of 400Mt at 1.65%.

“And we haven’t even found the edges yet. We [recently] put a drill hole to the north of the intended pit, a vertical hole for hydrology work. We thought we were going to be drilling into wall rock, into schists, but hit two metres of lateritic material and then we went into pegmatite again for 98m.

“This potentially adds another ~50Mt to the resource.

“[Neighbouring orebody] Carriere de l’Este is 1.2km long, ~ 200m thick and a lookalike for Roche Dure. It is a bit different geologically, but tonnes-wise it is probably the same.”

So, this is multi-generational project?

“Well and truly. Everyone thought AVZ were ridiculous when we stated an exploration target of 1 to 1.5 billion tonnes at anywhere between 1% and 1.5% lithium, but we are a third of the way there with the 400Mt at Roche Dure, which includes 132Mt in [high confidence] reserves,” Ferguson says.

“We can handle 29.5 years at the 4Mtpa throughput easily and are now doing a study into an expanded throughput rate which is almost complete.”

Would expanded throughput change the Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) numbers?

“I’ll let you suck on that one,” Ferguson says.

“Times have also changed since we completed the DFS in May of 2020. Pricing was a lot lower than it is now.

“We used $US699/t for SC6 [6% spodumene concentrate], and I think we used $US7400/t for primary lithium sulphate pricing. Based on that pricing we could be making $US380m EBITDA per annum. Very, very profitable.”

You also have the benefit of using hydroelectricity, which you say will cut carbon emissions substantially.

“We have a [hydro] facility down the road that needs to be refurbished as part of the deal we are doing with the government, and that is 90% of our greenhouse gas emissions gone,” Ferguson says.

“The hydro also makes us looks so good in terms of costs — we go from 17c to 20c per for diesel power generation down to 5c for the hydro. A huge saving.

“The idea is to have hydro plus solar; we are talking a 5MW-10MW system there to smooth things out.

“We are also looking at electric mining equipment, electric haul trucks – electric everything. The only part that can’t be electrified is the heat for the calcining process for the primary lithium sulfate (PLS).”

In the emerging world of carbon taxes will a low carbon, hard rock operation save money in the long term?

“Could it save us money? Possibly. Will it be looked at as a crucial factor in offtakes? Yes, it will,” Ferguson says.

“The two major points we take out of our discussions with European entities and battery manufacturers is that one – this border carbon tax they are talking about will be rolled out fairly soon.

“The second one is we would pay for disposal of the waste products that end up in Europe. Germany is one example – we would have to pay to get rid of our waste.

“The sweet spot for us is that we will be producing primary lithium sulphate (PLS).

“SC6 is 6% lithium, 94% waste, whereas our PLS is going to be 96% lithium, 4% waste. We won’t be shipping anywhere near as much waste around the globe – saving on transport and saving on those impending taxes and disposal costs on the other end.”

What is lithium sulphate?

“The normal process is dig it out of the ground, crush it, put it through a grinder roller, put it through a set of spirals to concentrate it to 6% (SC6),” Ferguson says.

“From there, the normal procedure would be for that SC6 to go into a hydroxide plant.

“The front end of the hydroxide plant is basically a cement kiln. It is a calcining kiln, probably 100 to 150m long. it rotates, it heats the spodumene up to about 1040 degrees. Then you put it into a tank where acid digests it.

“You filter it, dry it, and cake it. That powder is primary lithium sulphate.”

So, you’re just building the front end of a hydroxide plant.

“Correct,” Ferguson says.

“Everything talks about being vertical integrated, and we agree. We need to be vertically integrated; we need to be eventually producing hydroxide.

“But to produce hydroxide in country we will need the technology to do it, which we previously didn’t have. The front end, the cement kiln side of things, the sulphate side of things, is incredibly easy to do compared to the hydroxide.

“It made sense for us to go the first step, but not the second step.

“Now we have this deal with CATH – who are a hydroxide producer – and they are very keen to assist us to produce hydroxide as well.

“But the main aim for AVZ is to get the product over to Europe, start feeding the EU battery manufacturers. That probably means shipping PLS through to Europe and converting over there into hydroxide.

“It saves on the waste, costs, and everyone is happy they are getting a really good quality product.

“The quality of our product is high. There are four things [offtakers] look at – one is the mica, and anything below 2% is acceptable. We are sitting at about 1.5% in the product.

“The big one is iron. Our resource sits at 00.98% — just under 1% — but in the PLS product we are getting 0.4%-0.48%.

“That’s really, really good quality.

“The feedback we are getting from the guys converting our product is that this converts extremely well to a primary lithium sulphate, and it looks like it will convert very well to hydroxide.”

Are you still exporting spodumene at the start?

“To get the project up and running we need to do that, but at least 50% of the revenue stream will be from PLS,” Ferguson says.

“Under the 4mtpa scenario 700,000 tonnes of SC6 will be produced in total. We then take 160,000t of that to make 46,000t of primary lithium sulphate.

“The remaining 540,000t of SC6 is under contract to three Chinese convertors.”

Would you like to eventually just export the lithium sulfate?

“Damn right,” Ferguson says.

“Those contracts run between 3-4 years, and we’ve told them that we will commit to the 3-4 years to get the project up and running and pay off debt etc, but we expect to be converting over to PLS at some stage.

“If we expand operations – if we go from 700,000tpa to say, 1.4mtpa for example – I don’t want to be shipping 1.4mt of SC6 around the world. I would rather be sending out 150,000t of PLS.”

The Democratic Republic of Congo has a bad reputation as a mining jurisdiction. Is this a worry for investors, or has it been exaggerated?

“It gets a really bad rap, but I have been operating there since 2004, and had no issues whatsoever,” Ferguson says.

“Yes, there is bureaucracy, but it is Africa, so you deal with it.

“I will say that President Tshisekedi has been cleaning the place up. The business environment is improving. He has been courting a lot of people over in Europe and the US and there are a lot of companies starting to come back into the country.

“BHP are chatting with Robert Friedland, talking about coming back in. Meanwhile, you have the likes of Barrick and AngloGold Ashanti with their $US1.7bn, ~800,000oz Kibali gold mine in the north.

“Friedland’s Ivanhoe Mines has got the massive Kamoa-Kakula copper mine up and running and is now staging it to expand operations. I see it as a country where there is zero risk geologically. You can find big projects there.”

You have a good chunk of project funding locked in via your JV partner Suzhou CATH Energy Technologies. Where will the rest come from? Debt?

“Based on the 2020 DFS the cost to build the mine was about $US545m,” Ferguson says.

“CATH have dumped $US240m on the table for 24% of the project. But with that 24% they need to stump up extra cash [to build it], so it ends up being better than $US400m of the $US545m that is required.

“We only need another $US150m to $US200m and right now lenders, including a group of Pan-African Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), have voiced their approval of the project and want to get involved.

“They have given us letter of commitment, and we are comfortable that the number they are proposing to us is more than enough to satisfy the shortfall.

“We will be fully funded in the very near future. I would hope by the end of next quarter, Q1 2022.”

Other big milestones for AVZ coming up?

“Would suggest that we will probably have the mining licence before the end of this year – that is the big thing we are waiting for,” Ferguson says.

When will you be in production?

“We did say Q1 of 2023, but I reckon it will be Q2 now,” Ferguson says.

WoodMac says we need 20 large lithium mines by 2030 to hit Paris targets. Benchmark says something similar. Do you think this is even possible?

“There are 20 more Manonos out there? I don’t think so,” Ferguson says.

“And I don’t think you are going to get enough out of those 20 mines to hit that target.

“For AVZ, I tend to think we will be pushing as hard as we can to expand, because if there is further [offtake] interest the expandability of the Manono resource is just ridiculous.

“We are talking potentially 10 to 15% of the current market, and if we supersize, we are looking at we are probably looking at 25% of the market.

“I love to be able to be in that position, because I think at the end of the day our pricing is going to benefit from being a bigger mine.

“The 2020 study was $US371/t for SC^ FOB cost, and $2662/t for PLS. Those numbers I’m pretty sure will come down further [with scale].

“I think we could be a real disruptor if we wanted to — if it’s sunny outside let’s get on with it and make some hay.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.