Using the power of the crowd could disrupt mineral exploration as we know it

Mining

Mining

The mineral exploration industry must innovate as deposits get deeper, more complex, and harder to find.

There’s a growing cohort of companies using data science to drive exploration, folks like Kobold Metals, Goldspot Disoveries, Orefox, Solve Geosolutions and EarthAI.

Kobold, for example, wants to find rich cobalt deposits using what’s been described as “Google Maps for the earth’s crust”. TSX-listed Goldspot utilises machine learning, which it explains like this:

It’s an exciting time. Now imagine a miner tapping into the knowledge of 1000s of these data scientists and geologists to find the next big deposit.

It’s called exploration crowdsourcing, an innovative idea which harnesses the power of knowledgeable crowds to find the most prospective targets – quickly and cheaply.

It works like this. A company makes its private exploration data publicly available, challenging independent geologists and data scientists from around the world to find the next big deposit on their tenements.

The winning models get cash prizes, and everybody (hopefully) wins.

According to Holly Bridgwater from Unearthed, crowdsourcing could help drive up the discovery rate while reducing the amount of expensive drilling required to get a result.

“An internal team of geologists might be able to work on one or two geological models [at a time],” she told Stockhead.

“Using the crowd means you can develop 40 models in the space of a few months. You’re really able to speed up the exploration cycle.”

Crowdsourcing also fosters fresh ideas. Geologists are experts but they can be very focussed in that particular field, says Bridgwater.

“The crowd can provide new ways of looking at exploration data, by applying things like data science and machine learning which these [miners and explorers] haven’t used before,” she says.

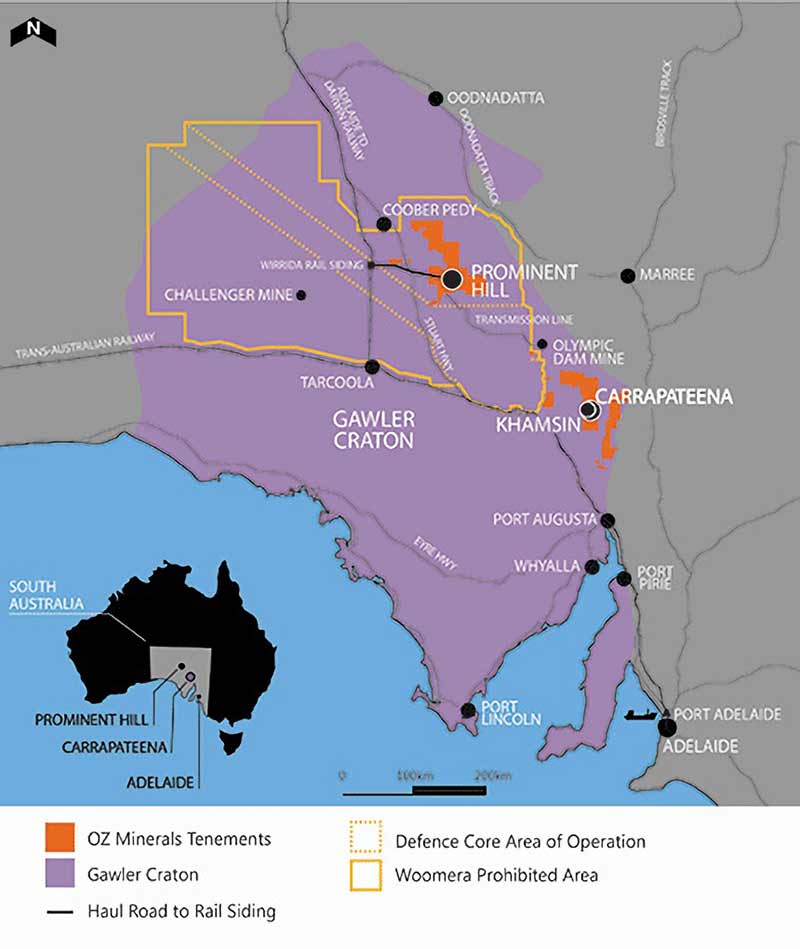

In December, mining company OZ Minerals (ASX:OZL) and Unearthed launched the Explorer Challenge.

The online crowdsourcing competition called for geologists and data scientists from across the globe to develop ground-breaking approaches to discover new exploration targets at a site near Oz Minerals’ Prominent Hill copper-gold mine in South Australia.

Participants in the competition had access to the OZ Minerals private 5-terabyte exploration database.

A $1 million prize pool was to be awarded to the winning ideas.

OZ Minerals’ chief executive Andrew Cole said it gave the company potential access to “thousands of scientists’ ideas and data” — something its relatively small team of in-house geologists weren’t equipped to deal with alone.

The challenge attracted more than 10,000 data downloads from over 1000 geologists, data scientists, start-ups, students, consultants, universities and research organisations from more than 60 countries around the globe.

It resulted in leading edge machine learning, data science and geological techniques being applied to the Mt Woods footprint, Bridgwater says.

It not only increased the confidence in Oz’s known targets — it generated more than 400 new ones in a very short time. The top priority targets at Mt Woods are now scheduled for drilling this year.

“There is usually no one best model to explain a mineralising system,” Bridgwater says.

“So there’s huge value in getting all these different models and combining them together.”

For example, of the 40 models that Oz Minerals received, data science-driven and geological approaches both predicted a number of targets in the same areas.

“Over time, by repeatability, and having multiple models predicting the same thing, you can have confidence in your targets,” says Bridgwater.

“It’s the idea of consensus that you can only really achieve with the crowd, because they are independent and come from different areas of expertise. It’s a really unique approach.”

It’s not a new idea; Gold Corp very successfully used it in the early 2000s. In fact, crowdsourcing is responsible for turning the struggling $100m market cap company into a multi- billion-dollar behemoth.

But despite the success rate, examples are few and far between.

The biggest barrier for these mining companies is putting their data into the public domain, says Bridgwater.

There’s a fear that someone may be able to learn from the public data and somehow take advantage of a target that the company hasn’t found yet.

“It took the Oz Minerals team a while to convince the board that this was a good idea; ultimately, it takes a big shift in mindset,” she says.

“Companies have to be comfortable with their data being public.

“We have lots of companies that are really interested in this, but that is real barrier for many of them.

“They’ve held onto this data so closely for so long; and even though they can see getting value from doing this, it a really big step to take.”

$1m is a really good incentive to get people to look at your data, but not every company has $1m laying around.

It’s something Bridgwater admits need to be looked at in more detail – how would a junior explorer incentivise a crowd to look at their data?

“We spoke to a few of the juniors who are very interested,” says Bridgwater.

“We have a few people who are interested in being part of a discussion – how do we develop this model to make it accessible?

“And it comes back to the incentive. If the juniors are happy for their data to be shared – and most of them are – how do you get the crowd to work on that data when you don’t have a $1 million?”

One way juniors could benefit is if State and Federal governments incentivised the crowd to dig into their mountains of publicly available geological data. Imagine what a crowd could do with that?

On a regional scale, crowdsourcing could reinforce where the known deposits are, and the predict where the most prospective new areas can be found.

Bridgwater says it’s a no-brainer.

“If thousands of people around the world use these data sets, it’s a really good way for the State Governments to promote the prospectivity of their regions,” she says.

“I think it’s an easy sell.”