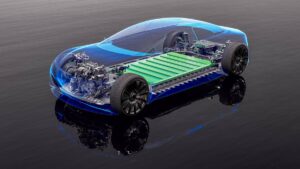

Could the EV industry pay up for exploration as critical metal demand grows?

Could carmakers join the search for the next big fish? Pic: Paul Souders/Stone, via Getty Images

- Carmaker investment in critical minerals from batteries to raw material mine development appears to be ramping up

- With so much on the line and new battery plants announced by the week, the question of supply endures

- Some experts believe EV makers could soon fund mineral exploration to secure their future stake of the minerals essential to their product

Two lithium mines, four cobalt mines, eight nickel mines, and nine graphite mines – each year. The headline figures around the mineral requirements of Tesla’s recently announced 100GWh Nevada battery gigafactory expansion were simply mindblowing.

The facility, which could well make Tesla the biggest Western producer of batteries, is just one of 13 +100GWh gigafactories in the pipeline globally, according to the seemingly battery omniscient Twitter account of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence Simon Moores.

Let’s borrow from the extremely reliable work of Stockhead’s resident mathematician Reuben Adams in his recent High Voltage story. Reuben’s numbers suggested the Tesla facility would require the following:

- 65% of the annual projected manganese production from Element 25’s (ASX:E25) Butcherbird project;

- 4x the projected 3500 tonne per annum cobalt output of Cobalt Blue’s (ASX:COB) Broken Hill project;

- More than 2x the expected 50,000tpa lithium production from Lake Resources’ (ASX:LKE) Kachi projects;

- 8x the projected 16,000tpa nickel production of Mincor Resources’ (ASX:MCR) Cassini-Northern operations; and

- 9x Talga’s (ASX:TLG) anticipated 19,500t annual graphite production.

Assuming all 13 of the forecast gigafactories go ahead – it’s hard to envisage an EV future without them – and all have a similar mineral input requirement…

Carmakers are clearly going to need more minerals. And to get more minerals, they’re going to need a clear path to future production.

Enter the deal between General Motors and Nevada-focused Lithium Americas Corp. The household name in car making committed a mammoth US$650 million in the Toronto-headquartered lithium developer.

That’s despite some concerns around native title at its flagship Thacker Pass project, which has a projected production rate large enough to supply 1 million GM cars annually.

GM has agreed to buy all lithium produced by Thacker Pass from its scheduled 2026 opening date – around 40,000 tonnes of the stuff per annum.

The deal was billed as the latest by an automaker to lock in supply of the key EV battery component, following on from deals between ioneer (ASX:INR) and Ford, and Piedmont Lithium (ASX:PLL) and Tesla.

The numbers above show the current rate of growth will require a great deal more critical mineral discovery.

Could carmakers fund exploration?

Stockhead caught up with Association of Mining and Exploration Companies CEO Warren Pearce to ask exactly that.

He’s a big believer.

“I think it’s really likely that we one day see carmakers funding mineral exploration to secure their share of critical mineral product,” Pearce said.

“The ready-made projects are mostly already gone, so then you’re looking for projects in the project development window and trying to buy up in that space – a lot of that is already taken up too.

“If you want to start looking to secure future supply, you probably need to start looking at the exploration space and identify companies that have good discovery prospects, and an ability to turn those discoveries into potential projects.

“It’s higher risk because you don’t know what you’re going to return, but it’s also smaller dollar outlay. You’re starting to see some of the Japanese and Korean investment organisations looking at that picture for some of the more sought-after critical minerals like lithium.”

Funding exploration would be a slow burn for those carmakers in immediate need, but a clever move if it were to allow minerals to be locked in for future.

At present, Pearce estimates it takes a minimum three and five years from discovery to production – that’s if a discovery is made.

“The reality of mineral exploration is that it’s a high-risk, speculative industry, but it’s one that is critical to actually deliver on project delivery and mining,” he said.

Hastening the need to secure critical minerals is the speed at which internal and external pressures are driving EV uptake globally.

“It is interesting watching the speed at which vehicle manufacturers are moving away from petrol, if you look at the timelines they’ve set themselves and that governments have set for them – it all means astonishing demand for critical minerals,” Pearce said.

“It’s very difficult to see how Australia is going to be able to turn on the critical minerals mined at the speed they’re needed in order to meet demand requirements.

“We’re looking at a very opportune time to be exploring and developing those projects. It’s hard to imagine an environment where there won’t be a lot of competition for product.”

Provided the punt comes off, those carmakers which circumvent their competitors by funding exploration efforts could be best placed in the mid to long term.

Will Australian exploration be an eventual direct beneficiary of the car industry’s insatiable desire for critical minerals? Time will tell, but signs appear promising.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.