What is Metaverse gaming, will it actually be a thing, and will it have less talking penises than Second Life?

Tech

Tech

About 40 years ago, I began my journey into the inescapable clutches of journalism as one of the very first gaming journalists in Australia.

Back then, computer games were largely text-based, as the graphic resolution of the home-cooked System 80 my old man painstakingly soldered and re-soldered together worked out to approximately 1 pixel per square inch on the old black-and-white portable telly we used as a “monitor”.

The games themselves were stored and loaded from audio cassettes, would take upwards of 30-40 minutes to load, and if the washing machine changed cycles during that interminable process, the spike across the power network in the house would corrupt the process and I’d have to rewind the cassette and start again.

Things these days are different, because not everyone in the world has the singular focus of a tech-addicted 10-year-old child of the ‘80s. And also because of the whole “technological progress” and “internet” thing.

One of the things I remember very clearly from my youth was the feeling that while the games (as they got better, and prettier, and faster) were 100% awesome, it would have been 100% more awesomer-still if I could have played them against other people, in real time.

LAN parties were, at that stage, still about a decade away from being on my radar – as were the games we played that warranted getting a lift from mum with the family’s only PC (and monitor, and a LAN cable) to a mate’s place for 48 straight hours of Doom.

Those weekends resulted in irreparable damage to my eyesight, and an electricity bill for my mates’ parents that would cripple the economy of Latvia.

But it was our world, and we loved it… then the internet happened.

When the internet became a thing, my family were early adopters. My old man blagged a hook-up from a friend of a mate who fell off the back of a Telecom truck, and it wasn’t long before those 48-hour sessions at the LAN party became a different kind of 48-hour session.

The kind where you waited 20 minutes for a postage stamp-sized image of the early internet’s hottest celebs, like Amelia Earhart or Ruth Bader Ginsberg, to download, and invariably crash right when it got to ‘the good part’. Those weekends also resulted in irreparable damage to my eyesight.

But, we were back in the ‘80s again, playing Multi User Dungeons (MUDs) with other lonely hyper-nerds from all around the world.

I played one particular MUD that has a very special place in online gaming history – it was called LegendMUD, and its Implementor (owner/god/final authority/guy whose bedroom had the server in it) was a fella called Raph Koster.

A lovely planet-sized fella who one day announced that he’d be stepping back from keeping our online home running, to lead the design on some hair-brained thing called Ultima Online, which he described as “just like a MUD, but with graphics and fighting and stuff”.

It was the first proper MMORPG, which I believe is a Welsh word, pronounced just how it’s spelled, meaning “lonely, but not alone”.

When Ultima Online launched in September of ‘97, it was hugely popular, and soon boasted a player base of around 100,000 which turned the game’s servers into helpless puddles of laggy mush.

The action was slow, and while technically “real time”, it wasn’t a patch on what gamers these days are prepared to expect, either in terms of performance, visuals or immersion. But it appealed to casual-ish gamers and hardcore roleplayers alike.

It’s that second audience which spawned something of an off-shoot idea, which – in turn – paved the way for what I know I am taking a very long time to get to. But please, be patient… I’m an old man reminiscing about how great things used to be.

Except for this next bit, which wasn’t great at all, except for the bits that are excellent.

Immersive, almost boundary-less immersive roleplaying was, for a long time, the Holy Grail of online gaming, after gamers grew tired of linear questlines, or being pigeon-holed as ultra-massive barbarians, willowy she-druids or bearded mages rumoured to be more enamoured with their spellbooks than with the aforementioned willowy she-druids.

For a few years, rumours swirled that a San Francisco company called Linden Labs was on the cusp of a major breakthrough, before the company tore the covers off a title called Second Life in 2003, ushering the internet into a new age of creative depravity.

Second Life is the archetype of persistent-world, immersive role-playing – and in many ways laid out the basic architecture of where the topic of this increasingly off-topic rambling essay has become: The Metaverse.

What Second Life offered included an almost limitless opportunity to reinvent yourself, visually and behaviourally (for better or worse), in a universe that was always on, whether you were there or not.

Freed from the constraints of most other massively multiplayer platforms, within months it was awash with some of the most ghastly perversions imaginable.

My own experiences of dabbling with it taught some profound life lessons, including:

I have seen things that there’s no coming back from… things that will haunt me for centuries after I’m dead.

But despite users having to navigate city-sized populations of aggressively unpleasant ambulatory penises, Second Life was pretty popular, and it remains a go-to resource for MMO/Metaverse devs and game designers who want to learn about how to do game mechanics right.

Probably the best part of Second Life’s design was that the back-end of the whole thing included relatively simple tools and interfaces to allow users to make not just their own “Everybody Dress like Genitalia” avatars, but pretty much… anything.

The rules were very simple: if a user created it, the user owned it (and all applicable rights to it), and that user could sell copies of it (the way a designer sells you a pair of shoes), rent copies of it for limited use (the way Blockbuster used to rent you VHS tapes to make illegal copies of using your mate’s VCR) or just put out into the world for everyone to access (like Mother Nature did with herpes).

Which leads us to something else Linden Labs got very, very right – the issuing of a digital token that could be swapped for goods and/or services, which gave birth to a full-blown market-driven economy.

The Second Life economy was powered by a closed-loop virtual token, rather imaginatively called the Linden Dollar (L$), which users could purchase directly from the developer, but never redeem directly for cash from the company.

Users could, however, buy and sell L$ tokens on the Lindex Exchange – an online space maintained by Linden Labs that operates just like a super-basic crypto exchange, where the value of a completely unbacked digital currency with an extremely limited user base and use case moves gently up and down through the market dynamic of supply and demand.

Unlike its modern-day crypto counterparts, however, the value of L$ doesn’t swing wildly like that too-friendly clothes-optional Czech couple you met on your last 7-day all-inclusive cruise through the Greek Islands.

Its value has remained remarkably stable for years, hovering around the L$250-to-US$1 exchange rate like a too-friendly clothes-optional Czech couple by the side of a grotty backyard jacuzzi, waaaay after it should be readily apparent that the party is over for the night, and it wasn’t that sort of party to begin with.

Think of L$ as kind of like those Disney Dollar things that The Mouse sells you on the way into their wretched theme parks, or those other not-real monies that my kids have poured the GDP of Trinidad and Tobago into for Fortnite or Destiny cosmetics.

The idea was that users would be able to spend L$ on stuff in-game, from little things a virtual drink through to life’s Big Stuff, like real estate.

Most people just put houses on theirs but several seriously big names in the corporate world (and stop me if this sounds at all familiar in today’s more modern context) got very excited about embracing this new technology, coughing up laughably massive sums of money for digital land in a universe where the thing that gives real-word land its inherent value – scarcity – doesn’t really exist.

IBM famously bought seven islands within Second Life to host Really Exciting Things, like training camps and seminars – kind of like an immersive version of today’s Zoom meetings, but where it’s far easier to turn up “dressed like Godzilla, except with cocktail wieners for teeth and a steady stream of neon-purple smoke emanating from every orifice”.

Likewise, early adopters of the idea of Second Life included artists and musicians, who either bought (or more likely rented) spaces to showcase their work, launch new songs or albums, or preview new film projects.

It marked the start of the very same headlong rush into the new tech space that we’ve been seeing from users, companies and creative types hurtling to be First to embrace and leverage the unmitigated Zuckerberg baby called The Metaverse.

Meta, the company formerly known as Facebook, has evolved waaaay beyond the digital equivalent of rifling through your ex-partner’s bins, largely because its founder – the Winklevoss Twins – realised that Mark Zuckerberg was a soulless despot with infinitely deep pockets and stopped suing him.

That allowed Zuckerberg the chance to devise a plan that would allow him to both build an online space for infinite creativity that he could rule with an Iron Terms of Service Agreement, and burn obscene amounts of money at the same time.

And thus, the Metaverse was born – giving this generation its own version of Second Life, but with real life consequences.

For starters, where Second Life was always meant to lead something of a detached parallel existence, the Metaverse is – by design – being built to become a symbiotic attachment to Real Life.

And while Second Life’s whole schtick was that it was – essentially – a game that let you make stuff to sell (or do) to other users for fake money, the Metaverse draws on its DNA as a platform first… and so developers are hard at work developing games to go inside this virtual space, rather than around it.

Which is where there’s big, big money being poured into game development, to provide the sort of sticky content that platform owners mutter about in their sleep.

By “big money”, I mean well into Burnt-by-Zuckerberg levels of cash.

Animoca Brands, the company overseeing a raft of Metaverse-friendly game titles and other Web3/Blockchain/NFT/ Random Buzzwords etc development projects, made huge news when it announced it was looking to raise up to US$2 billion to form a fund to drive the Next Big Thing in gaming.

Since that announcement, “FTX” happened and knocked a bit of the wind out of those – and everyone else’s – plans, but the company recently advised that its push for a more sedate goal of $800 million is still very much on the cards.

Animoca already has some serious notches on its bedpost in Metaverse gaming, after it got its Blockchain groove on through the acquisition in 2017 of Fuel Powered and Axiom Zen, the folks behind the CryptoKitties NFT craze/game.

If you missed the buzz back then, CryptoKitties took the acquisition and trading of very expensive JPGs to a whole new level – with just 50,000 Generation-Zero kitties ever made, it had that lovely built-in scarcity model that makes grown-ups part with lots of money to be part of the lark.

The sticky part of CryptoKitties (which ran on the Ethereum network, for those of you playing at home) was that users were able to “breed” their digital cats, because when a Mummy JPG and a Daddy JPG love each other very much, Not-Quite-As-Expensive Baby JPGs are made.

The userbase collectively decided on which traits were most desirable, and before an unsuspecting world knew what hit it, digital kitties were at it like digital rabbits and a lot of people got very rich.

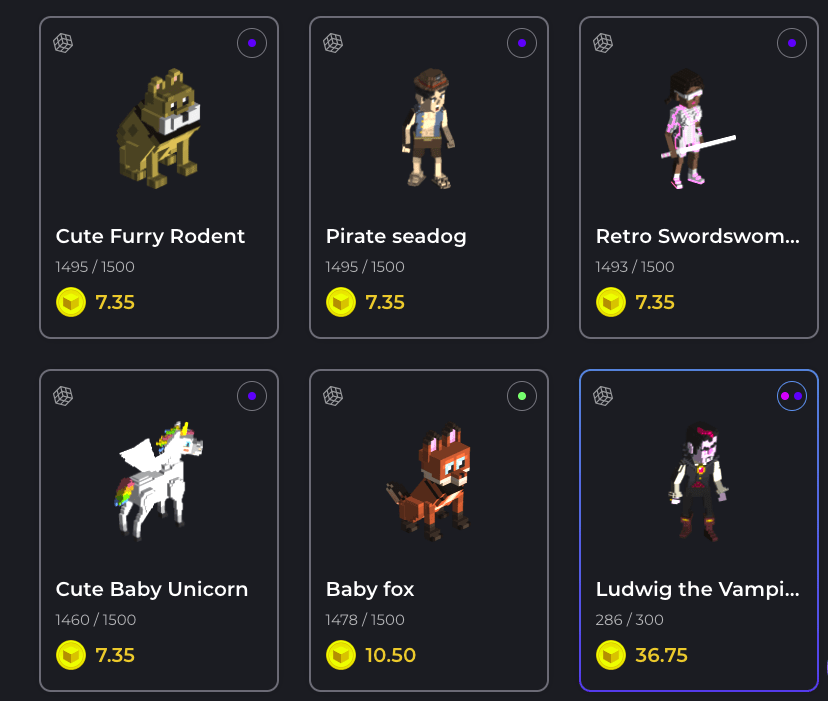

Off the back of that, Animoca went big on R&D, and has since brought a swag of the biggest titles in Web3/NFT/Metaverse gaming to the masses, including The Sandbox, which started life as a 2D mobile game built by developers Pixowl.

Animoca acquired Pixowl, the game was reimagined as a far more immersive and tinkering-friendly 3D open world prospect, and took off from there – part of online gaming’s tentative toddler-steps into the big-ticket Play to Earn space.

I’ve picked The Sandbox to bang on about because it represents the next “next step” in the journey for online gaming – and because of the lessons it clearly draws on from gaming environments like Second Life.

The underlying basic game mechanics are very similar – users can buy land, and use it for whatever they want to create.

It has its own digital currency, too – the SAND token, which is an ERC-20 utility token used for value transfers as well as staking and governance. Like other tokens, it has a finite supply (3,000,000,000, Animoca says), but it can be bought and sold on exchanges (like Coinbase and Binance) rather than being hemmed in by the developers.

And – again, like Second Life – users are able to earn their own SAND through their actions inside The Sandbox itself, either by making and selling their own in-game assets, buying LAND from the company to on-sell to other users or through (and this is where it all gets a bit Inception-ish) building their own games within the game for other users to play and spend money on.

Animoca says it’s 100% behind the game development side of The Sandbox, too, setting up a Game Maker platform to take the sting (and the coding heartbreak) out of building whatever’s in your head and bringing it to market.

It’s quite evident that it’s a logical iteration of gaming in general, in the same way it’s evident that Animoca’s been working very hard to bring organisations and brands on board that not only add depth to the entire prospect, but also the all-important “legitimacy” factor.

That last one is probably the most important aspect of them all.

It marks a much-needed psychological stepping stone between “how good were the games we grew up with?” and “Honestly, WTF does all this Crypto bizness even mean?” for a generation of gamers who are negotiating how, and why, their own kids are finding out that having fun is never “wasting time”.