Why are ASX stocks so in love with clay rare earths projects? A punter’s guide

Pic: SimonSkafar, iStock / Getty Images Plus

- Ionic Rare Earths (ASX:IXR) spearheads a growing list of clay rare earths explorers on the ASX

- Clay rare earths deposits are favourable over hard rock for a number of reasons

- ASX IAC stocks: a non-exhaustive list

For many years, the only rare earths you would find on the ASX were the hard rock kind, championed by miners and project developers like Lynas Corp (ASXS:LYC), Arafura (ASX:ARU), and Northern Minerals (ASX:NTU).

But these projects have their disadvantages.

They are expensive to build, and easy to get wrong. Of the 50 or so rare earths stocks outside China which emerged during the last boom in the 2000s, only two have entered production: Mountain Pass in the US, and Lynas in Australia.

In 2019, Ionic Rare Earths (ASX:IXR), then a $10m market cap tiddler called Oro Verde, acquired a rare earths project with a difference.

This one was clay hosted (IAC); something new for ASX investors, but not the industry. China, which dominates global REE mining and processing, gets most of its supply from IAC deposits in Southern China and neighbouring Myanmar.

By 2021, IXR was still the only IAC stock on the ASX, but by this time it was worth well over $100m as its flagship project moved through the development process. Then, in mid 2021, Australian Rare Earths (ASX:AR3) hit the bourse as clay REE stock #2. Punters responded very positively and, since then, a small avalanche of explorers have entered the clay REE space.

Why are these projects so popular among ASX stocks?

#1: THEY CONTAIN THE RIGHT RARE EARTHS.

Rare earth permanent magnets are a crucial component in wind turbines and in the drive train of hybrid and electric vehicles. There’s a couple of kilos of rare earths magnets in every EV, and about a tonne in every MW of power produced by wind turbines.

It is the next decade when we will see demand get a little out of control, driven by a projected seven-fold growth in electric vehicles. On top of that you have a forecast eight-fold growth in the offshore wind turbines sector over the next nine years.

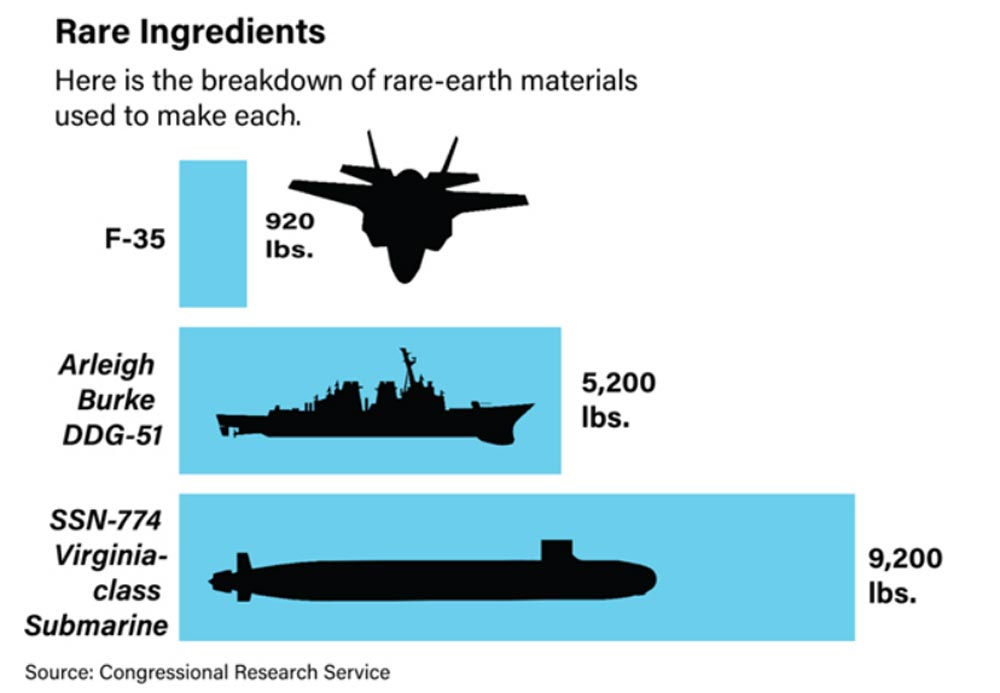

And then there’s defence. Just check out the amount of rare earths required to the keep the machines of war running:

By 2030, demand of magnet REOs is forecast to exceed supply by 40%, mostly driven by EVs.

That’s why investors should primarily be focused on the magnet rare earths – neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium.

AR3 managing director Don Hyma says clay hosted deposits are rich in the two key heavy rare earths elements, dysprosium and terbium.

“These are even more vital in making high strength permanent magnets than the two key light elements, neodymium and praseodymium,” he told Stockhead.

“It is the dysprosium and terbium that allows these magnets to maintain their high strength at elevated temperatures.

“If you didn’t have them the magnetic strength would decrease, and hence the motor would not be as efficient in the use of the battery power.”

Without dysprosium and terbium an EV may only travel 300km instead of 700km on a charge, Hyma says.

“Those two little elements are critical to getting the highest efficiency out of these motors.”

#2: CLAY HOSTED DEPOSITS ARE EASIER TO FIND, EASIER TO MINE.

Hard rock miners have to drill, they have to blast, and they often have to dig deeper to hit the orebody.

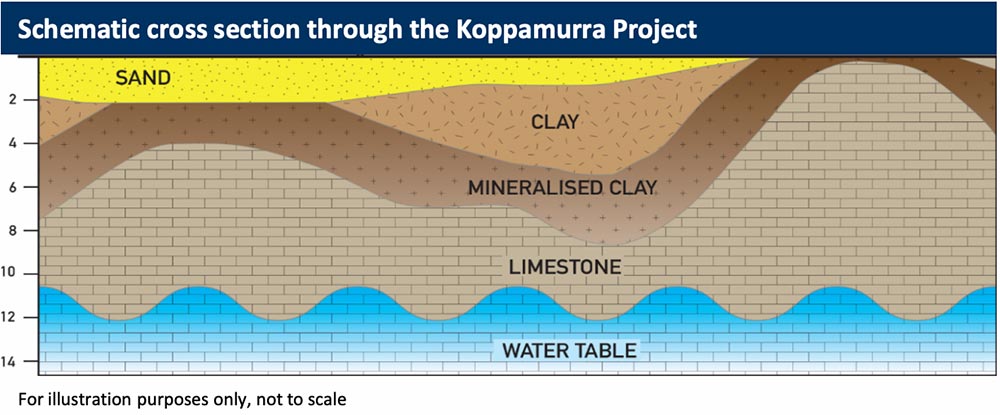

Clay hosted deposits are close to surface, usually between 1 to 10m deep.

They are also in clay, which makes them easy to dig. Unlike hard rock deposits, you don’t need to drill or blast. The strip ratio is also low, 1:1 in AR3’s case.

This is what AR3’s trial pit looks like:

“Its like earthmoving, really,” Hyma says.

As a result of being in soft clays so close to surface, these deposits are also low cost to discover and drill out.

“It only takes us about 20 minutes to drill a hole 12m deep,” Hyma says.

No chance you could do that in hard rock. Exploration results are also quite predictable, Hyma says.

“These clays lie horizontally, either on top of limestone or granite – a hard basement rock,” he says.

“In our case it goes for 40-50km – you just have to follow the limestone because the clay sits right on top of it.

“And as a result, it is very predictable to explore regionally.”

#3: PROCESSING IS CHEAPER.

Hard rock miners must crush, grind, and then put ore into a very large rotating vessel, where they elevate the temperature to 300 degrees Celsius, and add sulfuric acid to seperate the rare earths from the mineral.

This is called ‘cracking’, an expensive (capex and opex) step that clay miners can skip entirely.

“In hard rock mines the rare earths are physically bonded to the mineral so you can’t readily remove that REE from the mineral without elevating temperature and adding sulfuric acid,” Hyma says.

“We don’t need to build a huge expensive cracking plant. These aren’t small – these kilns are 100m in length, 5-6m in diameter.”

CLAY’S WEAKNESS: GRADE.

Hyma says the one disadvantage to clay hosted deposits is grade.

“We are talking about 0.1% rare earths in our deposits versus hard rock miners which could be between 2-10%,” he says.

“Our grade average is ~700ppm, or 0.07%.

“IXR, the first ASX clay rare earths stock, their grade is about the same.

“We have a big disadvantage on the rare earth grade of the clay, but that is easily offset by the advantages.”

But this isn’t a competition

We are going to need all the rare earths we can get, Hyma says.

“I think there has been a structural change in the rare earths industry since the early 2000s: demand for electric vehicles and wind turbines,” he says.

“And by the way, we are going to need both clay and hard rock developments if we are going to meet demand.”

China alone needs to find a crapload more feed.

“It has done a remarkably good job of developing not just the mines, but the technology to separate and then go all the way downstream,” Hymas says.

“They saw the value attached to a value integrated supply chain from mine to magnet.

“They are way ahead of us. But the challenge for China is that they are running out of feed in Myanmar and Southern China.

“I wouldn’t be surprised at all if you see far more activity by Chinese companies outside of China securing feed for their downstream plants within China.”

Then there’s the non-binding offtake deal between hard rock stock Arafura and auto maker Hyundai, which Hyma says points to a global “concern about magnet REE supply”.

“It’s the first time in my 30 years in the industry that OEMs have been coming up stream like that,” he says.

“It’s remarkable. They must be very concerned about supply.”

ASX IAC stocks: a non-exhaustive list

In April 2021 the clay OG released a scoping study demonstrating the potential for its ‘Makuutu’ project in Uganda to be one of the lowest cost rare earths operations in the world.

The project is one of the last large-scale undeveloped ionic adsorption clay (IAC) deposits globally with a recently updated 532 million tonnes at 640 ppm TREO resource.

This resource update will support the feasibility study currently underway, “which will now look at incorporating both a faster ramp up and greater annual production capacity driven by a material step change in Indicated resources”, the company says.

The feasibility study to be completed later this year will be used to support a mining licence application expected to be submitted before the end of October 2022. IXR aims to be in production in 2024 or 2025.

AUSTRALIAN RARE EARTHS (ASX:AR3)

The $35m market cap IAC REE stock has been a popular addition to the bourse.

Its Koppamurra project in South Australia and Victoria “is Australia’s largest prospective ionic clay hosted rare earth element deposit”, the company says.

It has an Inferred Mineral Resource of 39.9Mt @ 725ppm TREO, defined from less than 2% of the Koppamurra landholding.

A resource upgrade is pending.

Shares in PTR went ballistic in April on a major rare earth discovery at the Comet project within the Northern Gawler Craton of South Australia.

Shallow RAB drilling tested the top three metres of the prospective clay horizon where mineralisation encountered “impressive concentrations of high-value REEs”.

All 44 holes returned strong results with 23 holes hitting TREO > 1,000ppm, with PTR describing these intersections as similar in characteristics and grades to ion-absorption rare earth deposits of China.

IXR, AR3, PTR share price charts

Gold-uranium focussed MEU is hoping nearology (being ‘near’ another explorer’s mineral discovery) will help boost its share price.

In April, it highlighted the fact that its tenement boundary in the Gawler Craton adjoined Petratherm’s (ASX:PTR) rare earths discovery.

The micro-cap explorer announced the acquisition of a 469sqkm project prospective for ionic clay (IAC) rare earths in WA late last year.

The Salmon Gums acquisition is close to EMT’s existing ‘Cowlinya’ REE project. It is also a stone’s throw from recent IAC discoveries made by Mount Ridley Mines (ASX:MRD) (~35km away) and Salazar Gold (~20km away).

In July 2021 MRD identified clay-hosted REEs at its namesake project near Esperance, WA.

Drill holes have returned elevated REE extend over an area 25km long and 3km wide, representing approximately 2% of the Project area, and mineralisation is ‘open’ in all directions.

MEU, EMT, MRD share price charts

In late September, this newly listed copper-gold explorer joined the rare earths game, acquiring 1,380sqkm of ground in the Murray Basin (Victoria-South Australia border) prospective for ionic clay-hosted rare earths.

Early-stage exploration at Mitre Hill — either side of Australian Rare Earths’ (ASX:AR3) ‘Red Tail’ and ‘Yellow Tail’ deposits — kicked off late January.

AOA applied for a couple of tenements in South Australia prospective for rare earths in Sept/Oct last year.

The ‘Limestone Coast’ project is also in the same region as ‘Koppamurra’.

KTS’s main game is the ‘Mt Clere’ project in the Gascoyne, which is prospective for ionic type rare earths (IAC), mineral sands, nickel, copper, and PGEs.

KTA has also unearthed IAC elements at the ‘Rand’ project in NSW, which the company is mainly exploring for gold.

In February MEK acquired the giant 2,068sqkm Cascade project within WA Albany Fraser Mobile Belt which is believed to be highly prospective for clay-hosted rare earths.

The Cascade project is just to the west of Mount Ridley Mines’ (ASX:MRD) namesake project.

RBX, AOA, KTA, MEK share price charts

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.