When uranium booms, it will boom for a long time

Pic: Stockhead, Via Getty IImages

- Uranium bulls predicting a breakout in 2023, driven by an accumulation of positive news since 2019

- “There are some very high price scenarios that need to be taken seriously”: Bannerman Energy’s Brandon Munro

- Munro says the uranium bull market will likely to be more sustained than other high-flying commodities

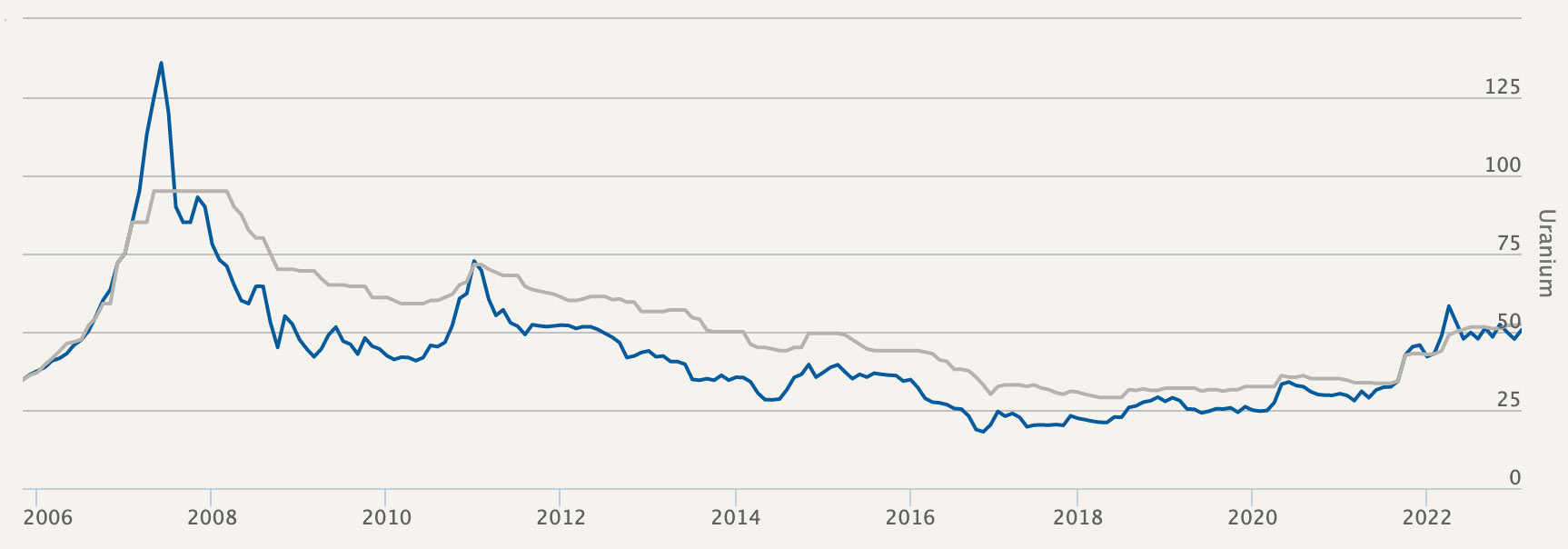

For years, uranium was the world’s worst performing commodity.

It hit the skids in 2007, just after the spot price peaked at $US143/lb, and was helped along its way by the Fukushima power plant disaster in Japan in 2011.

But since ~2018, the sector has been running at a structural deficit.

Large uranium inventories, one of the reasons prices stayed so low, were running down and after years of low prices no one had meaningfully invested in new supply.

In 2019, former managing director Mike Young of Vimy Resources – recently acquired by fellow project developer Deep Yellow (ASX:DYL) – said “if the [uranium] price doesn’t go up, if the contracts being written aren’t high enough to sustain production, then production stops.”

Spot prices were languishing at ~US$24/lb at the time, well below the US$60/lb needed to incentivise new production.

Then things started to happen.

In 2020, COVID caused substantial supply disruptions for large global producers like Cameco (Canada) and Kazatomprom (Kazakhstan).

Kazatomprom’s shutdowns that year slashed already lagging production by up to 10.4 million pounds of U3O8, or almost 8% of global output.

In August 2021, the Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (SPUT) started buying up physical uranium, taking it out of market circulation.

This uranium will not be on-sold for a quick profit.

Instead, pounds bought from the market by this vehicle will be sequestered for the long term and, crucially, each pound bought by SPUT will be one less pound available for end-users during the next cycle.

The buying continues to ramp up in 2023, with cashed up SPUT basically mopping up any pounds not contracted to utilities.

SPUT gonna gobble gobble gobble until the price squeezes out of control. That’s how this plays out…only question is when the the maniacs come to play. The idiots that buy doge coins. Or funded AARK. Or drive $tsla to crazy heights… they will come

— Kevin Bambrough (@BambroughKevin) February 16, 2023

The yellow(cake) ducks are lining up

In January 2023, Cameco CFO Grant Isaac told instos at the CIBC institutional investor conference in Whistler, Canada, the groundwork was being laid for a uranium boom.

Isaac said a perfect storm of inflation-related supply issues, a clean energy crisis prompting more governments to support nuclear reactor builds and life extensions, and Russia’s cancellation from international markets were all heating the water.

“Reactors we thought were going to be shut down are being saved,” he said.

“A fuel buyer who thought their reactor was being shut down didn’t procure any material, so there’s near term demand to deal with; [and] we’re seeing medium term demand in the form of reactor life extensions.

“On top of that we have … over 50 large reactors being built around the planet and perhaps even more exciting is we’re starting to see SMRs (small modular reactors) being built.

“While I say the demand outlook is the best ever, I’d say the supply outlook is more uncertain than it’s ever been.”

Will this boom begin in 2023?

Brandon Munro is chief executive at advanced uranium play Bannerman Energy (ASX:BMN). He is also former co-chair of the World Nuclear Association’s nuclear fuel demand working group and currently sits on WNA’s board Advisory Panel.

He says 2023 has marked a positive shift in uranium sentiment, driven by this accumulation of bullish news since 2019.

This could be the year things finally explode.

“The potentiality in 2023 for the uranium market and therefore uranium equities is profound,” Munro told Stockhead.

“There are some very high price scenarios that need to be taken seriously.”

According to Numerco, uranium is currently paying ~US$52/lb, below the long-term incentive price of US$60/lb generally accepted as the entry point to bring new production online.

But inflation has changed things, with experts estimating that a new price of between US$75/lb and US$80/lb will be necessary to incentivise enough production to meet uranium demand this decade.

Either way: when uranium booms, it will boom for a long time

2023 may be the year it kicks up a gear for uranium equities, but this won’t be a short cycle.

Munro says the uranium bull market will likely to be more sustained than other high-flying commodities because of the nature of the length in the fuel cycle.

“The uranium commodity cycle is a lot longer than, say, a typical seven-year commodity cycle we got used to in base metals,” he says.

“That’s because the consumption pattern in uranium is a lot longer.

“First of all, reactors, once they are in the construction phase, are a [consumer] of uranium over a long period of time.

“A commitment to constructing a reactor probably starts seven years before it goes into production. And the long-term contracting cycle lasts for up to 10 years.

“Such long demand pattens elongate both bear markets and bull market runs in uranium.

“The last bear market started in 2011, and we only really came out of it in the end of 2020. So, you can use that 10-year cycle as a proxy for the bull market that started two years ago.”

And then there’s the supply side.

“The adage in commodities is that ‘the cure for high prices is high prices’, but it takes so long to get uranium mines permitted and up and running, that there isn’t the responsiveness to higher prices that you would expect to see in other commodities,” Munro says.

“In uranium there is limited downside risk from current price levels, with a significant probability of upside risk,” he says.

“And there are same extraordinary upside risk scenarios that should be part of any investment decision.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.