‘They are desperate for nickel’: QPM’s Stephen Grocott on the impending battery supply chain trainwreck

Mining

Mining

To make battery grade nickel and cobalt from ‘laterite’ ore is tough.

The incumbent route is High Pressure Acid Leach (HPAL) which is expensive and historically prone to failure.

Townsville-based Queensland Pacific Metals (ASX:QPM) will use the patented Direct Nickel (DNi) process instead, which it says is cheaper, less capital intensive and most importantly, more forgiving than HPAL.

Some of the world’s biggest battery makers agree.

In February, planned output from its flagship ‘TECH’ project was doubled due to strong offtake interest from big battery makers like LG Chem and Samsung.

In June, LG and steel producer POSCO signed deals to invest a combined $15m in the advanced nickel-cobalt project developer.

Shares will be issued at a price of ~13.5c — a 16.8% premium to the one-month VWAP at the time.

QPM has also signed binding offtake agreements for the sale of 10,000t nickel and 1,000t cobalt with the two companies.

The company is now knee-deep in a project Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) – the most advanced of the studies prior to final investment decision – ahead of first production in 2023.

QPM managing director Dr Stephen Grocott explains why nickel is the best way for investors to get exposure to the electric vehicle thematic.

“The TECH Project has a number of distinctions from other junior battery metals projects,” Grocott says.

“We don’t have a mine, and the risk associated with a mine. We are essentially an advanced battery materials manufacturing facility.

“We import ore from New Caledonia, one of the leading – if not the leading – global exporter of nickel ores, truck it 40km to our project site where we chemically process it into high purity battery nickel and cobalt products.”

“Direct Nickel (or DNi) was invented by a guy in the US who sold the licence to a former ASX-listed company called Direct Nickel,” Grocott says.

“That company and the CSIRO spent ~$30m developing and piloting DNi. In 2011 they did something like 19 pilot plant runs [a smaller version of the real thing] in Perth at whopping great facility.

“I’ve never seen anything piloted so extensively.

“They tried to commercialise it, and they got close, but it never went ahead.

“The reason is because there was only really one market for nickel back then – stainless steel.

“In the 2000s, China developed something called nickel pig iron (NPI) which remains the cheap way to get nickel into stainless steel. When poor old Direct Nickel were trying to commercialise their process, the only market was stainless steel effectively and they were competing with low cost NPI.

“But timing is everything. Battery sector demand is now emerging, and to go from NPI to battery nickel is not economical.

“NPI is 14 % nickel, 86% iron — if you want nickel for the battery market you need 99.995% purity nickel sulphate.

“The advantage of HPAL and DNi is that you can go straight through to battery grade nickel sulphate. NPI can’t.

“The market has changed, and we aren’t competing with NPI anymore.”

“Only two of the dozen HPAL projects in the world have been successful. All of the others have been abject failures,” Grocott says.

“HPAL is difficult to get right.

“While HPAL plants use sulfuric acid, which is cheap, the plants are capital intensive, they are difficult to operate. And we can only build them as whopping great units.

“DNi is easier to scale up.

“It also uses nitric acid which is the far superior acid. DNi process recycles more than 98% of the nitric acid back, which would be too expensive to use otherwise.

“And as a side effect of recovering all that nitric acid you produce all these by-products – high grade iron ore, magnesium and aluminium, which we will convert to high purity alumina.

“Anything you don’t get out of the ore is silica, which is about 15% to 20% of the ore mass.

“Everything else ends up as a saleable product as a by-product of the process.”

“At today’s iron ore price, the hematite would be 35% of our revenue,” Grocott says.

“But in our financial model it’s 10% of our revenue, the magnesium about 3%, and HPA another 15%.

“These by-products attract different markets and help spread our risk.”

“Yes, in both capital intensity and operating costs,” Grocott says.

“When you do it on a nickel equivalent – because of the by-product credits — the operating costs are very, very low.”

“Absolutely no question. After this is proven I can’t see anyone building another HPAL project.”

“They employed a global multinational technical firm who put us through the griller [during the due diligence process],” Grocott says.

“Their due diligence review went for about 5-6 weeks. Everything from ore supply through to process technical risk – you name it.

“It’s a vote of confidence in the process by them.

“It is also a sign that they are desperate for nickel supply.”

“It has to be a good project, but there is a market anxious to secure supply,” Grocott says.

“I’ve described it as a supply chain train wreck.

“So when people ask ‘who are your competitors?’ I say ‘there are no competitors’.

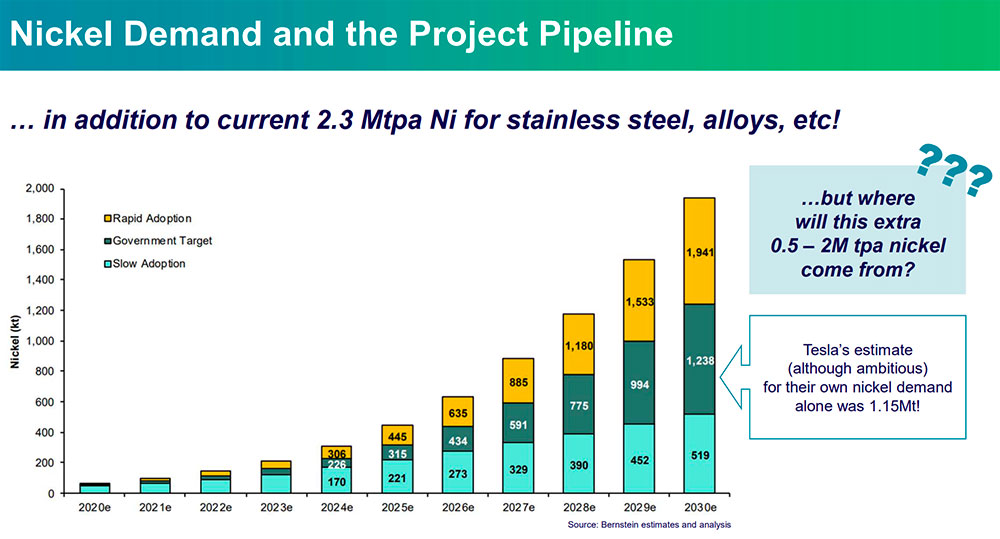

“There are no competitors because if every nickel project in the world went ahead, we are still not going to meet the conservative demand projections.

“Nickel prices are going to go through the roof.”

“Zero. I am not aware of a single nickel player who has an agreement like this. And to have it with two is incredible,” Grocott says.

“Originally our PFS was for 0.6 million tonnes of ore a year; now it’s 1.5mt after [offtakers] asked is we could do this bigger.

“Yeah, we can do it bigger, we said, but it’s going to cost a lot more money.

“Then they asked if we could do it faster. Yes, we said, but it going to going to cost money, and you are going to need some skin in the game.

“That is essentially what led to this deal. In March we went out and raised $20m, now they [LG and POSCO] have come to the party with $US15m.

“Skin in the game, sharing the risk. It’s a fair deal; in fact, we think it is a great deal.

“They need a lot of nickel over the next few years, and 10,000 nickel tonnes is significant chunk of their supply.

“They would be crazy to say that we are a slam dunk – there are always risks with new projects – but if we don’t produce the amount that we have said we are going to produce, it will be a serious problem for them.”

“We have talked about the potential for project equity or significant company equity, but we don’t want to lock ourselves in with that,” Grocott says.

“We believe this project can sustain at least 60% debt. We are in discussions with NAIF as well.

“Our preference is not tie up the remaining 5000 to 6000 nickel tonnes in offtake unless we have to. The spot market is likely to be pretty attractive.

“But if the debt providers want a bit more tied up in offtake that’s not a problem – there’s plenty of others already approaching us.”

“The feasibility study will be finished first quarter next calendar year,” Grocott says.

“Assuming we have finance we will be starting construction second quarter.”

“Yes. It’s the one market everyone got the most wrong,” Grocott says.

“They said if global nickel production was 2.5 million tonnes, and battery demand was only 200,000 tonnes, there would be plenty of nickel to go around.

“But they were wrong. It’s uneconomic to move the majority of global nickel production – NPI — into battery grade nickel sulfate.

“So when you look at the global market it’s not 2.5 million tonnes that is available for batteries; it’s about 250,000 to 500,000t if you are lucky.

“And projected demand by 2030 is at least another 1 million nickel tonnes a year.

“You’re talking about a CAGR approaching 30%.

“The nickel is not going to be there.”