‘There are a lot more to be found’: Chalice Mining’s Alex Dorsch says Gonneville is just the start

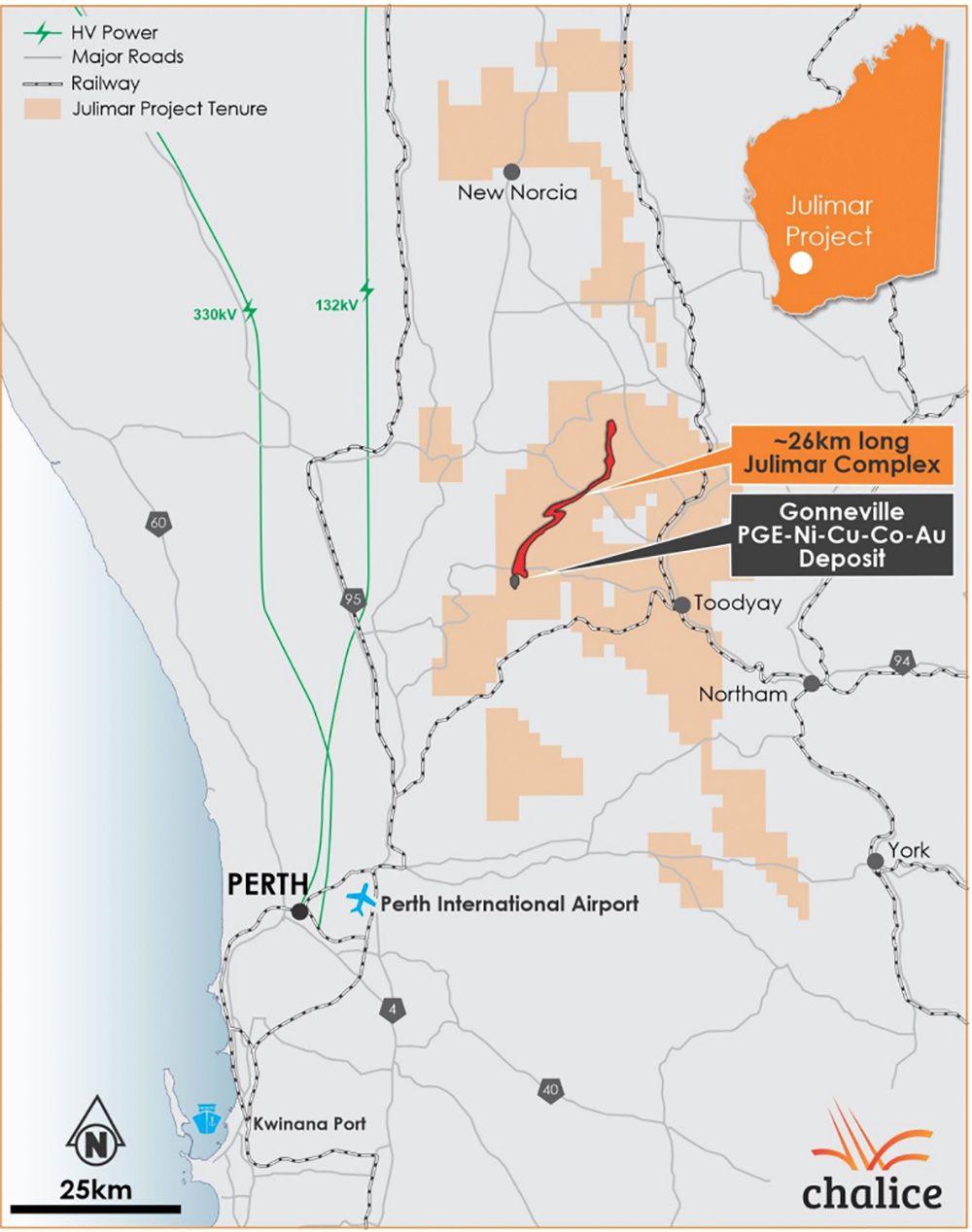

In FY18, Chalice Mining (ASX:CHN) pegged the Julimar tenements in WA after a review of limited historic exploration and geophysical data showed the project to be prospective for nickel, copper and platinum group elements (PGEs).

A so-called ‘generative’ project, Julimar was an early-stage greenfield opportunity in a completely untouched region.

It was largely designed to keep CHN’s project pipeline full and wasn’t intended to be a focus.

In early 2020 a six-hole, 1,500m drilling program kicked off as an initial test of three targets identified via ground-based electromagnetic survey.

The ‘Gonneville’ high-grade nickel-copper-palladium discovery was made with the first-ever drill hole, with an intercept of 25m at 8.5g/t Pd, 2% nickel, 0.9% copper and 0.11% cobalt from 46m.

Absolutely unheard of.

The rest is history. Last month, CHN hit an all-time high after announcing a truly spectacular maiden resource of 10Moz Pd-Pt-Au, 530,000t nickel, 330,000t copper and 53,000t cobalt — the equivalent of 1.9Mt of nickel or 17Moz of palladium.

That’s the largest platinum group elements discovery ever in Australia, and the largest nickel sulphide discovery globally in 20 years.

But this is just the beginning of the journey, managing director and CEO Alex Dorsch says.

Dorsch speaks to Stockhead about the upcoming scoping study and the numerous ‘Gonneville’ sized discoveries he believes this region could be hiding.

How big is this discovery going to get?

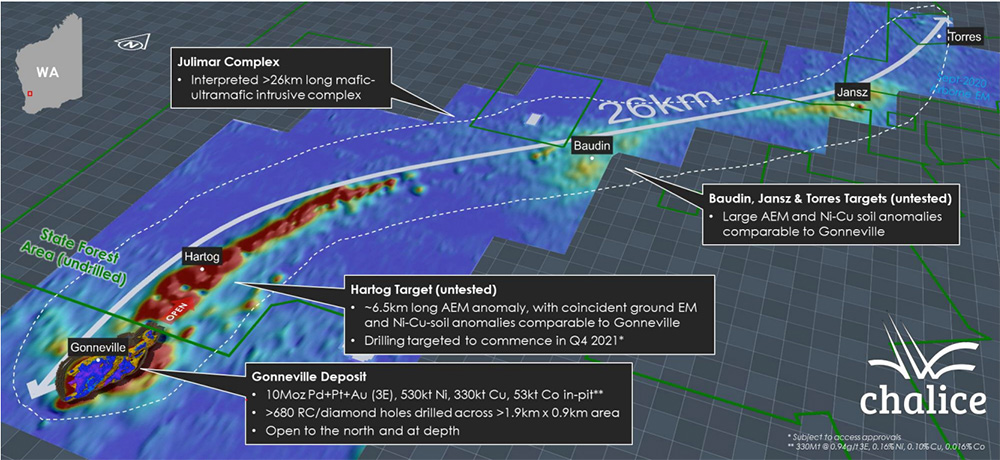

“We are almost certain that our complex itself is at least 26km long, and we are seeing evidence of sulphide mineralisation 50km to the north of our discoveries,” Dorsch says.

“The resources cover just 7% of that 26km long strike length and have only been drilled down to about 600m.

“Deposits of this nature, in places like South Africa and Russia, are routinely mined for [decades] down to depths of 1500+ metres.

“If you look at the Norilsk discovery story, that played out over 30-odd years.

“It was initially found by some Russian prospectors in the 1940s, but then it wasn’t until ~25 years later that the high-grade core of the system was found, about 25 to 30km away from the initial discovery.

“So, you get an appreciation for just how long it can take. It is quite nuanced, this style of exploration.

“They didn’t have all the wonderful modern exploration techniques we have at our disposal – but still, we can see at least a five-year exploration journey ahead of us.”

What is your hit rate on those conductors so far? How often do you drill into sulphides?

“There were upwards of a dozen or so conductive plates which were strong drill targets at Gonneville,” Dorsch says.

“We have only drilled one barren conductor, which means 1 out of 12 was a false conductor, coming from something that wasn’t mineralisation.

What a fantastic hit rate.

“It’s a very good hit rate, and we now have ~30 mid to late time plates to drill just at Hartog [just north of Gonneville],” Dorsch says.

“If you consider that only one out of 12 were not mineralisation [at Gonneville], then what we are seeing at Hartog could point to a significant continuation of this resource.”

I remember you talking last year about a target in the state forest which you found especially exciting. Is that Hartog, the one you are about to drill?

“The 6.5km long Hartog anomaly, which is immediately north of Gonneville in the Julimar state forest, is one of the clear standout drill targets on the planet today,” Dorsch says.

“But before we found Julimar we were particularly excited by the geophysical signature at Baudin, further up in the middle of the state forest.

“That was the one rated highest prior to the discovery, and the only reason we didn’t start drilling there was due to lack of access. We could only access Gonneville to begin with.”

So, you have approvals to drill in the forest?

“We haven’t got the approvals yet, but they won’t be far away,” Dorsch says.

“We are very excited to test all the way along the Julimar complex, as well as doing the first ever drill holes at Hartog in the coming weeks.”

How should we be assessing this orebody so far? Is there an analogue we should be looking at?

“Since the discovery hole we looked straight to Norilsk [the largest nickel-copper-palladium deposits in the world] as a comparison,” Dorsch says.

“When you are talking about 100 per cent sulphide content rock it is quite analogous to the ultra-high grades you get at Norilsk.

“I think a lot of parallels have been made with South African reef style PGE deposits, but this is really nothing like that.

“We don’t have any reef style mineralisation. Our chrome values are also very, very low which is something that is quite different to South African [deposits].

“The chrome content of the reefs can be problematic in recovering and smelting the nickel and copper. We are very fortunate that we have low chrome, ultramafic host rocks.

“We are seeing very good results in floating and producing two separate copper and nickel concentrates.”

I even saw an equivalent with BHP’s famous Mt Keith mine, I think on a grade equivalent basis. But I thought that was interesting as well.

“Mt Keith is really a nickel only deposit, but if you look at it in terms of tonnage and grade, they are comparable,” Dorsch says.

“The difference is that Mt Keith has a very insignificant high-grade component.

“With Gonneville that is not the case at all. We have a 74Mt high grade core to Gonneville, which makes it much more attractive as a mining proposition.

“We can target those shallow high-grade tonnes early in the mine plan.

“I think that’s what differentiates Gonneville from a purely disseminated sulphide deposit like Mt Keith.”

How will the nickel-copper-PGEs be processed?

“Most of the test work that we have done to date has been focussed on a sequential flotation flowsheet targeting the 74Mt high grade component of Gonneville,” Dorsch says.

“The sequential flotation firstly floats off copper, gold, and three-quarters of the recovered platinum and palladium.

“That leaves the nickel, cobalt and roughly one quarter of the recovered PGEs to go into a separate product.

“That is very important. Often nickel-copper-PGE projects of this nature don’t have the ability to produce two separate products.

“Having the ability to produce selective products – keeping the copper out of the nickel concentrate – is incredibly important from a payability perspective when you are dealing with smelters.

“The other advantage of Gonneville is that there are very limited impurities. We haven’t seen any material quantities of arsenic, cadmium or selenium which can be very problematic in these types of concentrates.

“The concentrates we are producing are very clean, which means they attract very good payment terms.”

What can investors expect from the scoping study?

“Our exploration journey isn’t anywhere near complete, so we are viewing the Gonneville scoping study as a detailed snapshot as to what the initial stages of mining may look like,” Dorsch says.

“It will be a very, very comprehensive scoping study. Processing, throughput, mine design, market and offtake will get covered in detail.

“This is not a brownfields gold discovery outside of Kalgoorlie, or a nickel sulphide discovery near Kambalda where you can effectively use everyone else’s data to put together a project scoping study.

“This is a greenfields discovery, a new type of discovery in a new province. We really need to do the studies on this project from the bottom up.

“There is quite a lot more rigour, a lot more detail going into the studies that you would typically see for a brownfield or near mine discovery.

“[The scoping study] is likely to be followed by studies on stages 2 and beyond, which should – we hope – involve additional resources from the Julimar state forest and potentially additional processing beyond sequential flotation.”

What is your opinion on ‘nearology’ in this instance? We haven’t seen much success around previous tier 1 WA discoveries like Nova or DeGrussa. Are there more big deposits to be found in the region?

“I believe there are a lot more to be found. Absolutely, no question at all,” Dorsch says.

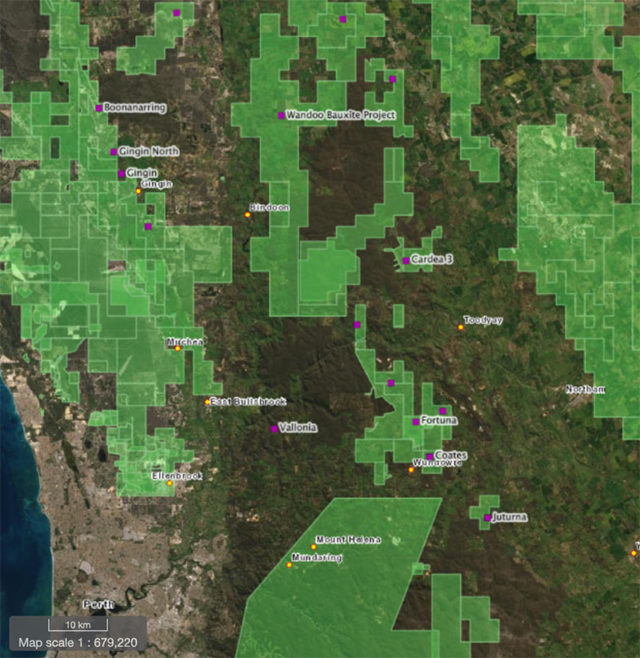

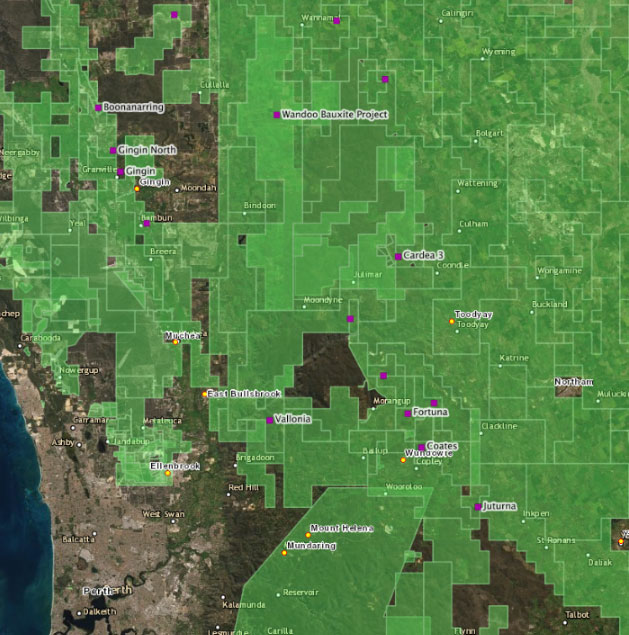

“Before our discovery there was really ourselves, Caspin and Liontown – now Minerals 260 (ASX:MI6) — holding exploration tenure in the area.

“Post discovery – and before we made it public — we went and selectively acquired about another 8,000sqkm of ground extending about 300km south and about 600km, 700km north of the discovery.

“We got first opportunity to go after every bit of prospective-looking ground in this new province.

“Of course, we could not capture everything. If we had, we would’ve ended up with 100,000sqkm and extraordinarily large expenditure commitments.

“We were selective in taking the first, second and third tier targets we could see from all the publicly available data.

“But we know we were dealing with imperfect information. The province hasn’t really been explored at all.

“As more data is acquired across this province, more opportunities will be highlighted. All that info is going to take some years to unfold.

“If you look at the Fraser Range and the areas around DeGrussa you probably would be a little bit disappointed by nearology outcomes.

“Unfortunately, these big deposits don’t always repeat.

“In saying that, there are a lot of examples around the world where they repeat beautifully.

“One that comes to mind immediately is the Norisk and Talnakh discoveries, which are about 25 to 30km apart. There is also about 25 years between them.

“The other one is the prolific Thompson nickel belt in Canada [over 18 nickel deposits estimated to have produced over 5 billion lbs of nickel since 1959].

“You can never be sure with geology, but the West Yilgarn province which we largely control is almost totally unexplored.

“There are years of work in front of us, but we have the capital and some of the best explorationists for this is style of mineralisation anywhere on the planet.”

You also have a stake in Caspin Resources (ASX:CPN), and a project joint venture with Venture Minerals (ASX:VMS). What made them stand out from all the other explorers in the region?

“We’ve kicked the tyres on all our competitors in the province. We think those two are clear standouts,” Dorsch says.

“We are early-stage strategic investors in Caspin for obvious reasons; their tenure predated our discovery, and they have some very interesting early-stage results.

“At Venture’s ‘South West’ project, previous explorers thought that sulphides discovered down were of VMS [volcanogenic massive sulphide] origin. Our model is slightly different; we think there could be an orthomagmatic system.

“That’s why we have selected those two.

“Saying that, we keep an open mind. In the exploration game you never want to run out of options, and you never want to be inward facing.

“We monitor everything that happens in the province, and we will move strategically in response to what we see at the time.”

CPN, VMS share price charts

You spoke about the state forest before. Is there anything to worry about from a permitting perspective, being that close to Perth?

“Fortunately, Julimar state forest is not a national park; it’s basically the lowest conservation level of Crown land in WA. That makes it very much open for mining and exploration,” Dorsch says.

“We have been working with the State Government for a long time now to gain access to that area, to see what is underneath that Julimar state forest.

“Of course, the proximity to Perth and communities up there is one of the unique challenges of this project.

“But we have a material quantity of future-facing green metals in the area, and I think as a society we can’t be selective given how scarce and rare these types of discoveries are.

“The reality is that the mining industry is going to have to make hundreds more discoveries like Gonneville to satisfy the demand for metals in the transition away from fossil fuels.

“What I’m hearing from our stakeholders is that this message is being heard loud and clear.

“Had we just found a run of the mill bauxite, gold, or iron ore deposit it would be a different equation, but we have a very rare discovery [which is] exactly the world needs.”

What will be some of the company’s major news flow for 2022?

“We are still drilling at Gonneville, so we expect to see continued results from that work,” Dorsch says.

“We are anticipating access for initial drilling in the Julimar state forest shortly.

“After that it’s metallurgical test work updates through the early part of next year, culminating in a resource update and publishing of the scoping study by Q2 of 2022.

“A very busy seven months ahead of us. There really hasn’t been a slow month since our discovery. We have been absolutely going hammer and tongs for good reason.

“Besides Julimar we have our Falcon Metals spinout that should be listed by the 22nd of December, and all the other projects in the portfolio where were we are doing early exploration work.”

Why do you think Chalice still has upside from here? What makes it an attractive investment?

“It’s the rarity of a tier 1 scale discovery, in a poorly explored province, in the tier 1 jurisdiction of WA,” Dorsch says.

“We have years of exploration drilling ahead of us to fully understand the scale of the Julimar district, and the wider West Yilgarn.

“How many discoveries will we end up making?

“It’s why I think Chalice is such a unique investment — we control of what is clearly the most exciting mineral province anywhere on the planet.”

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.