‘Risk money’ could flow into explorers when the tech bubble bursts

Hillary Clinton secures the Democratic presidential candidate nomination in 2016. This is a visual gag with layers. Pic: Jessica Kourkounis / Stringer/ Getty

The medium-to-long term fundamentals for copper, nickel and a range of other battery-related metals are overwhelmingly positive.

But talk to any listed small cap explorer and they’ll tell you how difficult it is to squeeze cash out of the market right now.

The performance of the struggling junior end of the market against the larger miners, who are actually making money (mostly), could not be starker:

Typically, the type of investment that goes toward exploration will also buy speculative stuff in other industries. Right now, a lot of this speculative capital is being funnelled into unlisted tech and cannabis.

Lion Selection Group’s Hedley Widdup calls it “risk money”.

“All [risk money] requires is one: a good story, and two: safety in numbers, or others buying the same idea,” Widdup told Stockhead.

“And it tends to do one industry at a time.”

It’s almost correction time

After QE3 (the third round of quantitative easing by the US Federal Reserve in 2012) the global population of tech unicorns – privately held start-ups with reported valuations above $1 billion — went from 33 to 150 in about four years.

Two years ago, the US-based National Bureau of Economic Research had already concluded that 65 out of 135 of unicorns were overvalued.

Widdup says an awful lot of cheap money also flew into the cannabis space.

“Cannabis companies – comprising just 2 per cent of the listed capitalisation on the TSX — were responsible for raising 22 per cent of the fresh equity on the TSX last year,” he says.

“You have a huge amount of money trying to force itself into a small space which causes phenomenal capital growth.”

Widdup believes money will start flowing back into the junior mining/exploration space once these bubbles burst.

This idea has historical precedent.

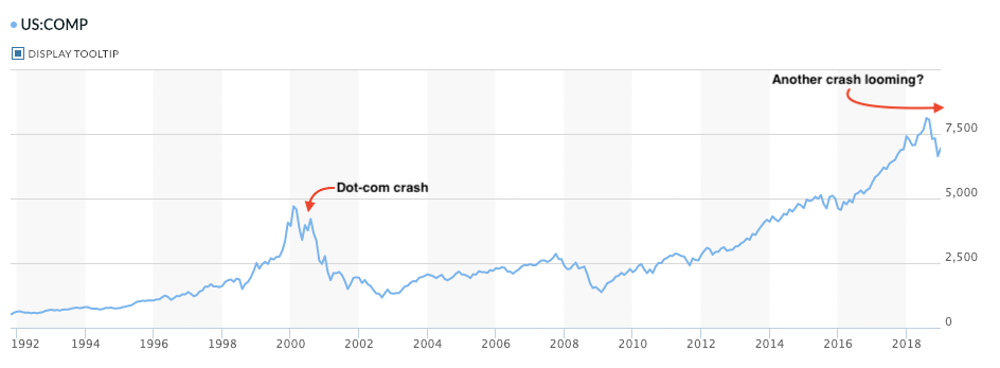

The dot-com bubble was a period of speculation driven by the growth of the internet. It peaked in March 2000, before crashing. Badly.

“It wasn’t until that dot com bubble burst and all that money washed out, that the junior mining market started to recover in 2002,” Widdup told Resources Rising Stars conference delegates in July.

“We didn’t just see a recovery in stock prices; we saw in it in capital raisings, and we saw it in IPO trends.”

The cycle we are in now is not massively dissimilar from the cycle we saw from 1999/2000 onwards, says Widdup.

For example, in October last year, the Wall Street Journal reported that 83 per cent of US IPO’s in the first three quarters of 2018 were losing money.

That’s the highest on record.

The previous high point – 81 per cent – was recorded in 2000 during the dot-com boom.

“I have never in my career seen so many massive-loss-making, revenue-growth-chasing companies go public and trade at such lofty, nay absurd, valuations,” Montgomery Investment Management’s Roger Montgomery wrote in July this year.

“And the pile of red-ink at the profit line has never been higher either.”

The latest example is US co-working space startup WeWork, which is laying the groundwork for what could be one of the largest IPOs of the year.

The company, nominally valued at $47 billion, has already lost $900m in the first six months of 2019.

How do we know when the bubble bursts?

Widdup says he is looking for indicators that tech and cannabis money is starting to get skittish.

Things like challenges in listing tech companies at the valuations initially sought, as well as declining valuations of those already listed.

It took between 12 and 18 months for this “risk” money to come back into exploration after the last tech bubble burst in the 2000s.

But it doesn’t have to be an event, per se.

“A movement of cash from one sector to another could be gradual and might manifest as stopping buying, or selling in order to buy elsewhere,” he says.

Risk money falls out of love with one thing when it becomes smitten with something new, Widdup says.

“And having had a pretty reasonable break from exploring – well, absence makes the heart grow fonder, doesn’t it?”

- Subscribe to our daily newsletter

- Join our small cap Facebook group

- Follow us on Facebook or Twitter

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.