Post-COVID-19 has fast-tracked EVs from ‘golf carts’ to must-haves

Pic: Bloomberg Creative / Bloomberg Creative Photos via Getty Images

The global roll out of electric vehicles (EVs) was occurring at slower pace than many predicted — until post COVID-19 stimulus put a rocket underneath it.

Most recently, Germany joined France as the second major European economy to drop a large sum of post-lockdown stimulus on driving the adoption of EVs.

The COVID-19 pandemic also dented supply chains around the globe, making Europe more determined than ever to secure its own battery supply chain and drastically reduce its reliance on China.

This has seen European governments accelerate their financial injections into the EV and battery metals space.

Germany is doubling EV subsidies to €6,000 ($9,745) for vehicles that cost up to €40,000. These new subsidies are on top of an existing €3,000 grant already received by automakers per vehicle.

Berlin is also setting aside €2bn of the total €130bn package to develop the country’s EV charging infrastructure, which will include a mandate that all fuel stations provide charging facilities.

And the country is injecting €1.5bn into its domestic battery cell production.

According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, Germany has 75 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of battery capacity in the pipeline out to 2024 — with VW, Tesla and CATL among those building out significant capacity over the next five years.

Benchmark estimates that cobalt demand from these megafactories could reach up to 6,000 tonnes by 2024.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance, meanwhile, says EVs share of total car sales is still small, but is rising fast. It expects that by 2040, over half of all passenger vehicles sold will be electric.

By 2030 there will be about 26 million EVs on the roads, compared to just 2 million in 2019.

EVs becoming a ‘no-brainer’

“There were trends in play which had reached tipping points … what COVID has done is accelerate those trends,” Joe Kaderavek, CEO of ASX-listed Cobalt Blue Holdings (ASX:COB), told Stockhead.

“Particularly on the EV front, the sheer amount of stimulus, and the generosity of the stimulus on a per car basis, is going to make EV purchasing, particularly in the EU, a no-brainer.

“It’s no longer a case of ‘is it cheaper?’ It’s clearly cheaper if the Germans are offering you a €9,000 subsidy on a car that costs up to €40,000.”

Kaderavek pointed to a recent UBS poll that, for the first time in its history, showed that on a like-for-like basis the majority of buyers would now choose an EV over a petrol car.

“That’s a trend that was in place prior to COVID-19 and the gap has narrowed significantly, where 10 years ago battery electric vehicles were seen as effectively inferior quality, short range, golf carts if you like,” he said.

There have also been significant government bailouts for big automakers.

France, for example, has earmarked €8bn, comprising a €5bn bailout package for Renault and EV subsidies.

“It’s going to completely retool Renault,” Kaderavek said. “It’s a bit of a common-sense question: do you think the French are actually going to retool with outdated technology or do you think they’re going to retool for cars they can sell in the future?

“No doubt some of that money will be spent tooling up very high-quality vehicles with high emissions standards to meet the EU standards. But the lion’s share of it will go into EVs.”

Kaderavek believes this will spur on competition between countries as they fight for top spot in the EV market.

“What we’re seeing with Renault is a really good example globally of government money — taxpayer money — being used to make decisions today that Renault management might not have made for a few years under their own steam, let alone have their own capital to make those decisions,” he said.

“As a result, the French are targeting a 1 million EV production capacity, which will make them the biggest EV maker in the European nations, and no doubt that will lead to an arms race of sorts between the various nations who want to get ahead.”

Cobalt will also have its day

This is all expected to significantly step up demand for battery metals – yes, even cobalt.

The global lithium-ion battery market is projected to reach around $136bn by 2030.

Two years ago, the boss of the biggest electric car maker said he wanted to stop using cobalt in his car batteries, but that has been a lot harder than he (and others) anticipated.

Since Tesla’s Elon Musk made those comments back in mid-2018, several experts have explained just why battery makers cannot eliminate cobalt from batteries.

There has been plenty of tinkering with the chemistry, for sure, and there has even been a shift to other battery types – like the lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) battery that seems to be favoured in China.

The problem with LFP batteries, however, is they don’t give you the range.

Which is why the majority of EV makers still favour the nickel-cobalt-aluminium (NCA) and nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM or NMC), of which cobalt is still very much a necessary component.

Cobalt is mainly used to make the cathode in lithium-ion batteries. It is used to stabilise the chemistry. Batteries include an anode (negative) and a cathode (positive) and the electrical current flows between the two.

“Cobalt doesn’t actually add to the battery’s electromotive properties. Cobalt is cement, it’s glue effectively,” Kaderavek explained.

“Cement in concrete is what cobalt is in a battery, and because it is the highest cost part of the cathode, they’re trying to take it out and you can only take so much of it out before the cement collapses.”

Cobalt demand, prices still set to rise

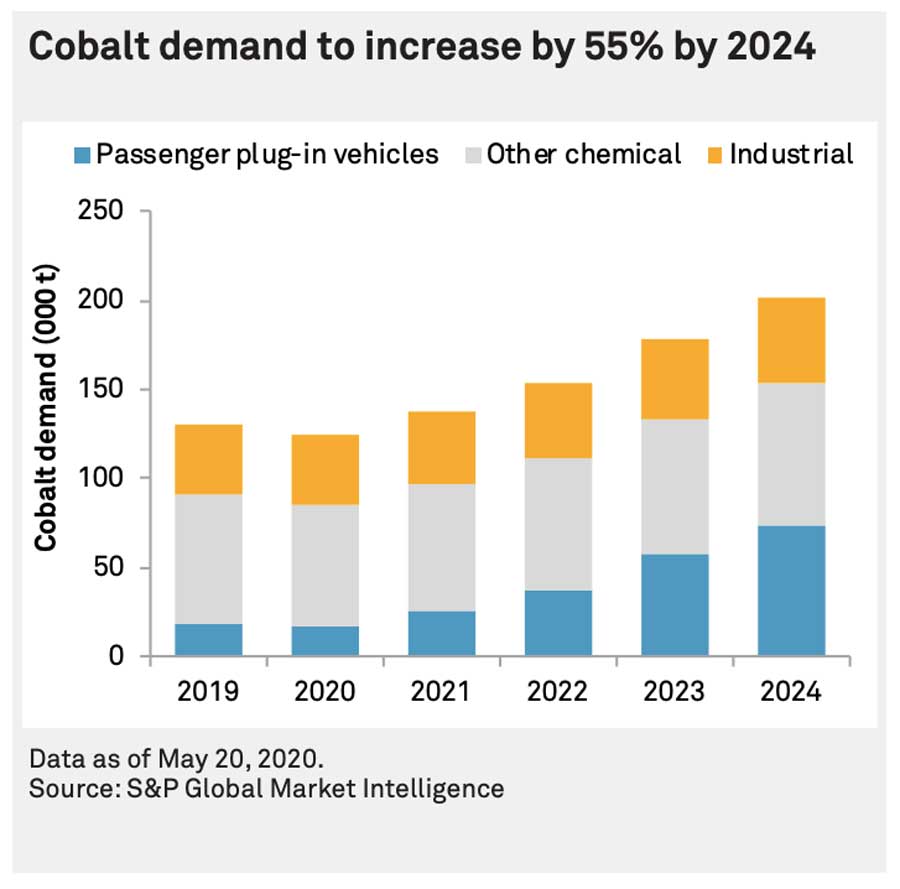

Although market forecaster S&P Global Market Intelligence warns that there will likely be “greater demand uncertainties” for cobalt than there will be for lithium because of the various chemistry choices, demand is still heading north.

S&P Global expects cobalt demand to increase by 55 per cent between 2019 and 2024.

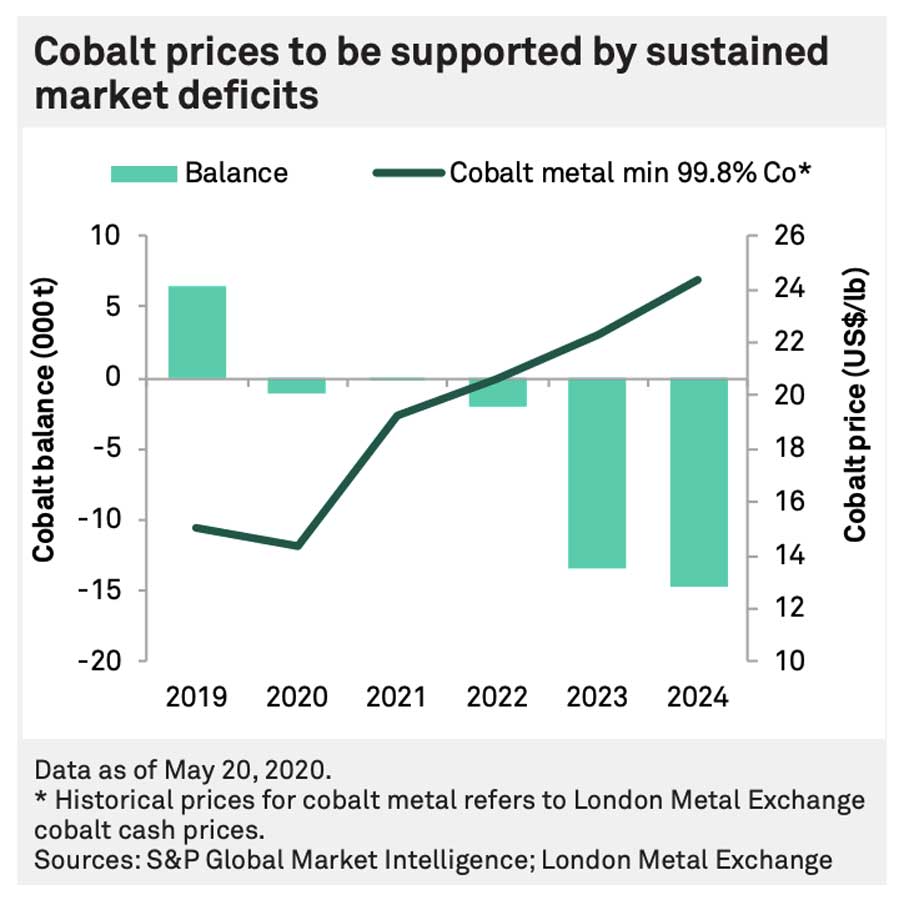

At the same time, cobalt prices are expected to be supported by sustained market deficits.

S&P Global predicts the deficit will persist in 2023 and 2024, which would see the cobalt price average $US24.39 per pound ($US53,771 per tonne) in 2024. That’s almost a 90 per cent increase on the current price.

Low cobalt, but not no cobalt

Cobalt Blue’s Kaderavek told Stockhead the quantity of cobalt in a battery would likely hit a “theoretical minimum” of around 7 per cent.

“If you think about a high-end, high nickel battery, think about 8-9 per cent cobalt by weight in the cathode,” he said.

“The NCA, which is the Tesla battery, is probably 7-8 per cent, even though Musk has tweeted about hitting 5 per cent, but no one believes him.”

Earlier this year major car maker GM said it was making a nickel-manganese-cobalt-aluminium (NCMA) battery.

“The NCMA battery is the GM/LG Chemical battery and that’s rumoured to be around 7-8 per cent cobalt as well,” Kaderavek said.

“So it’s all hitting this theoretical minimum which seems to be, call it 7 per cent.”

Very opaque market

The cobalt market, however, is not an overly transparent market, which makes it a lot harder to predict supply, demand and price movements.

Guy Le Page, director and responsible executive at Perth-based financial services provider RM Corporate Finance, told Stockhead the cobalt market was probably one of the opaque-est markets of any of the metals.

“It’s only been trading on the LME for about 10 years but the supply/demand metrics around cobalt are pretty hard to understand,” he said.

“Most of the world production is a by-product out of the Congo and Zambia.

“As a primary play it’s extremely difficult because the volatility is so high, and the spikes are so short and sharp that any project where cobalt is the primary driver has proved challenging.

“One thing I do know though is to substitute cobalt is extremely difficult.”

Le Page reckons it has the potential to reach the heady heights of $US95,000 it got to in March 2018.

“It went over $US90,000 a tonne a couple of years ago, I can see that happening again but it’s totally unpredictable,” he said.

There are very few primary cobalt producers in the world, and that’s because of the tough nature of the business and the lack of primary cobalt mines.

Around 98 per cent of global supply comes as a by-product from either copper or nickel mines.

The copper belt in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Central African Republic and Zambia yields most of the cobalt mined worldwide.

The Bou Azzer mine in Morocco is currently one of the world’s only operating primary cobalt mines and has been in operation since the 1930s.

Cobalt has been declared a critical mineral by the EU because globally, only around 100,000 tonnes is produced each year.

This has led to a dearth of cobalt explorers on the ASX. The closest one to a pure play cobalt company is Cobalt Blue, which when in production will have a mix of 80 per cent cobalt and 20 per cent sulphur.

Cobalt Blue is advancing its Broken Hill project in New South Wales towards production.

Finite margin, downstream could be key

“We’re aiming at 4000 tonnes of cobalt equivalent, which makes the Broken Hill project the largest greenfield cobalt project in the world,” Kaderavek said.

But for cobalt to be a profitable business, the trick is to bypass the Chinese refiners and turn it into a product that can be sold straight to a battery maker instead.

“We understood early that in Australia if you’re going to mine cobalt and make a margin, you’re going to have to refine it to something that meets a battery maker halfway, otherwise you’re losing virtually all the margin,” Kaderavek said.

Cobalt Blue has spent “considerable time” on the downstream processing side of things and believes it has a good handle on the type of product it needs to make to be able to sell direct to battery makers.

“What 80 per cent of the world’s cobalt does is go through the refining industry in China, we’re going to bypass that and sell straight to the battery maker,” Kaderavek said.

“So we’re going to make the maximum margin from the product.”

Cobalt Blue is aiming to have a pilot plant up and running by Christmas this year.

The company is part of the Western Australian government’s $135m Future Batteries Industries Cooperative Research Centre (FBI CRC) at Curtin University in Perth.

On the industry front, the FBI CRC is being backed by big companies like Lynas (ASX:LYC), BHP (ASX:BHP) and IGO Limited (ASX:IGO).

Several small caps besides Cobalt Blue are also connected to the initiative, including Galaxy Resources (ASX:GXY), Pilbara Minerals (ASX:PLS), Syrah Resources (ASX:SYR), Protean Energy (ASX:POW), Clean TeQ (ASX:CLQ), EcoGraf (ASX:EGR), Volt Resources (ASX:VRC), FYI Resources (ASX:FYI) and Australian Vanadium (ASX:AVL).

The research partnership of 58 industry, academic and government partners wants to address industry-identified gaps in the battery industries value chain.

WA Resources Minister Bill Johnston announced just yesterday that a new research report found the state was capable of housing a battery manufacturing facility.

“As identified in this report, and the WA Future Battery Industry Strategy, the next step to add value to Australia’s supply chain is to move into cathode precursor and cathode active production,” Johnston said in a statement.

The FBICRC’s cathode precursor pilot plant is expected to be located at CSIRO’s Waterford facilities.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.