Nickel prices are at 11-year highs as EV demand heats up. Can we find enough of the battery metal to feed the beast?

Pic: Getty

As prices scale to levels not seen in over a decade, experts believe it will be “all hands to the pump” to secure the nickel supply needed to deal with a rush in demand from electric vehicles over the next decade.

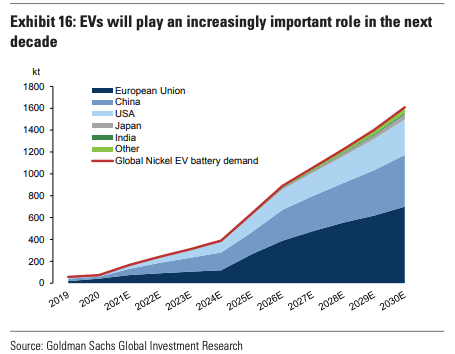

Nickel expert Jim Lennon from Red Door Research in London, the former chairman of Macquarie Bank’s commodities team, says the world will need 1.3Mt of nickel for batteries by 2030.

That’s 1Mt higher than 2021 when Lennon says an estimated 320,000t or 12% of mined supply was processed for use in battery storage.

The concern? Just ~700-750,000t comes from nickel sulphides, the kind of primary nickel currently being supplied into the battery market, and that number hasn’t moved for two decades.

“That’s the crux of the matter, between 2020 and 2030, you need close to 2 million tonnes new nickel supply,” Lennon told Stockhead.

“So, you know, I say about one million from batteries, but also another 800-900,000 tonnes for other applications like stainless steel and the like.

“The nickel market in 2020 was about 2.6 million tonnes. By 2030, it’s going to be close to 4.5 million tonnes.

“So you need a couple of million tonnes more supply. So where is that coming from? You know, that’s the issue.”

With battery demand finally beginning to make an imprint on the market in a real way, warehouse supplies critically low and prices hitting 11-year highs, what will it take to bridge the gap and can the base metal keep up the momentum?

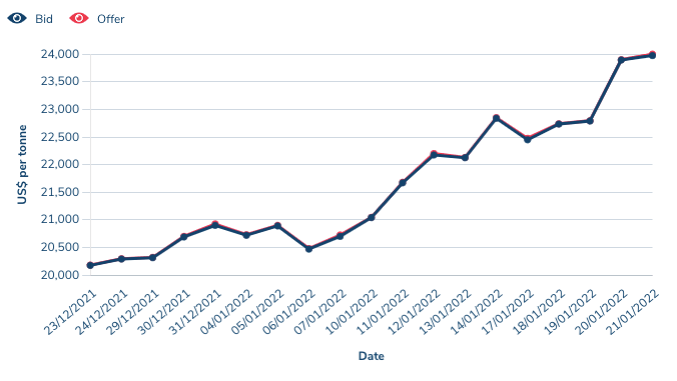

Prices hit US$24,000/t

Nickel’s long predicted reawakening has accelerated in the past week as short supply and falling stocks on the LME warehouse has weighed on the market.

The market was already extremely tight last year after supply disruptions from Indonesia, the world’s largest producer in the form of nickel pig iron and Russia’s Norilsk, the world’s largest nickel sulphide producer.

Cash nickel metal on the LME settled at US$23,975/t on Friday, 14.5% higher year to date and more than double the price on offer when the pandemic began in March 2020.

The three-month delivery price of US$23,715/t is at a big discount, known as backwardation. That means buyers are desperate to get their hands on nickel right now.

LME stocks fell below the psychological 100,000t mark at the start of the year with just 93,480t in stock Friday, while the Shanghai exchange is virtually bone dry.

Lennon said the price run has been unusual given stainless steel production, 70% of the downstream market for nickel, has been weak in recent months. Case in point, nickel pig iron which can only be used in steel production is trading at a big discount to LME briquettes of up to US$3500, with nickel sulphate for battery precursor also at a discount.

“There’s been no new fundamental news over the last month that would have caused us to get mega bullish,” he said.

“Normally news that is price responsive is a supply disruption. Last year we had floods in Russia at Norilsk and they lost half their production for three months.

“And then you had the strike in Canada at Vale’s operations, and the price responded to that. So this time around, there’s been no new supply news (and) actually in Indonesia the nickel pig iron number for December that came out showed a big jump in production.

“Those of us who are following the physical market closely, we’re quite scratching our heads over the recent rally.”

But there has been a swag of news about the desperation of miners to buy nickel projects with an eye to its future supplying the EV supply chain, such as BHP’s decision to invest an initial US$50 million and up to US$100 million in the Kabanga nickel mine in Tanzania, Tesla’s supply deal with Rio Tinto-backed Talon Metals’s nickel project in Minnesota, a rare US source of supply, and Elon Musk’s separate backing of Prony Resources, which is aiming to turn around the trouble-plagued Goro mine in New Caledonia.

Battery market driving nickel prices: The smoking gun

Suggestions battery makers are hoovering up LME stocks, as they move from a ‘just in time’ production model to a ‘just in case’ bet on the future of battery demand and to shield against shipping delays, could be impacting prices as well.

LME-grade briquettes can be converted into nickel sulphate for batteries where “class 2” forms of nickel like nickel pig iron cannot.

“The only evidence we’ve got is the smoking gun evidence,” Lennon said.

“So in other words, you can look at the rate of consumption of nickel in the batteries in China in each month, and it has kind of plateaued in the fourth quarter.

“But the amount of nickel imports has shot up, so relative to the first half, nickel metal imports into China went through the roof. They went from 10-15,000t a month, to 25-30,000t a month.”

Goldman Sachs, which said the nickel market shifted from a projected 49,000t surplus to 159,000t deficit in 2021, already posted a 12-month target of US$24,000/t in January.

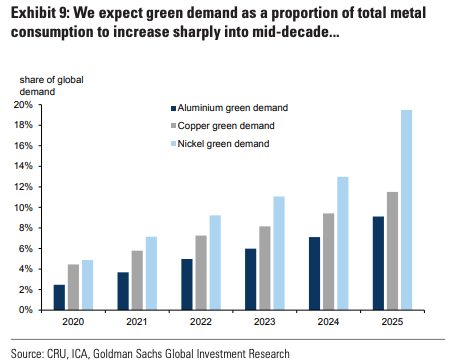

The investment banking giant is projecting a 30,000t deficit this year, up from 13,000t previously, as supply recovers, but is doubtful Indonesia can increase supply rapidly enough to cover the market, leading to “open-ended large deficits from 2025”.

“With close to balanced markets in both 2023 and 2024, then followed by the beginning of the open-ended large deficits from 2025 (113kt), we think nickel is entering a phase of stronger pricing which will sustain moves above the $20,000/t level,” analysts wrote in a client note.

Lennon says it is unlikely prices will remain at current levels throughout 2022 as supply ramps up in Indonesia and Russia, increasing by up to 15% this year.

“If the supply gets delayed, or you get more disruptions, then it can sort of trade in the current range of US$20,000-23,000. The scenario under which prices go to US$25,000-30,000/t I think would have to be something really extreme,” he said.

“The market is quite well balanced between supply and demand. It was in big deficit last year because of the soaring demand, the rate of growth in demand this year will be slower than last year. Last year was kind of a post-COVID recovery.

“The rate of supply growth will be much faster. So it’s kind of a balanced market, in my view, so I don’t see a lot of upward momentum in prices.”

China’s investment in converting class 2 lateritic nickel in Indonesia into matte that can be turned into a battery grade nickel is also increasing, with Tsingshan expected to bring 50,000-100,000t of capacity in this area online this year.

The ability for supply to keep pace with demand is likely to change in the years ahead, however.

Aussie miners attracting interest from all quarters

Ironically, while nickel prices have soared, miners and explorers have seen their share prices stagnate.

IGO (ASX:IGO), owner of the Nova nickel mine and soon to be the owner of Western Areas’ (ASX:WSA) in a friendly $1.1 billion takeover, is an outlier, though it has lithium on its books as well in the form of its stake in the Greenbushes lithium mine.

Mincor (ASX:MCR), which expects to restart its Kambalda nickel operations by mid-2022 and support the reopening of BHP’s Kambalda concentrator, is up only 1.82% year to date, Panoramic (ASX:PAN), which sent its first shipment from its reopened Savannah mine in the Kimberley late last year, is down 5.17%.

Nickel Mines (ASX:NIC) which will open its new Angel project in Indonesia in September, hit record highs earlier in the year but is up just 3.42%YTD. Andrew Forrest-backed Poseidon Nickel (ASX:POS), which plans to bring its high grade Silver Swan mine and Black Swan processing plant back into production by March 2023, is down 8.33%.

Its managing director Peter Harold, who previously ran Panoramic during the last nickel boom in 2007, said while lithium stocks have captured the attention of investors in the EV thematic, nickel will have its time in the sun.

“It’s interesting that we’ve seen very strong interest in lithium stocks throughout the world and people are starting to look around and see what other commodities are going to benefit from the electric vehicle revolution,” he said.

“I don’t like to call it a revolution, I just think that as the world moves away from internal combustion to electric vehicles the demand for graphite, copper, cobalt and nickel all go up.

“I think everyone’s beginning to look around not just at lithium but certainly at copper, certainly nickel, certainly cobalt and graphite too.

“People will start to take positions and I think this year will be where there’ll be a lot more activity in the nickel space and I think that also leads to M&A activity and that also drives interest from investors as well.

“I think you’re going to have the combination of higher nickel prices and the EV thematic being a lot more front and centre in investors’ minds. There’s a lot more ESG focused funds putting money into green energy and that means those investors will be looking for investments in the things that produce electric vehicles.

“I just see a very changed environment which is totally different to what I experienced in the mid-2000s.”

Cash flowing into battery nickel

That investor interest has been in clear view in the past week with institutional investors tipping $75 million into Centaurus Metals (ASX:CTM) to complete a DFS on its 20,000tpa Jaguar nickel sulphide project in Brazil.

There were also plenty of buyers for shares in new nickel IPO NiCo Resources (ASX:NC1). A spin out from Metals X (ASX:MLX), its shares shot up almost 200% in its first three days of trade after listing on Wednesday.

NiCo owns the Wingellina nickel-cobalt laterite project in WA’s remote Ngaanyatjarra Lands. While development costs have long been the biggest challenge there, there is hope the coming shortfall could deliver prices that would make a project like Wingellina possible.

Lennon said increasing the supply of nickel sulphides, often regarded by proponents as “class 1 nickel”, will be particularly challenging in the years ahead.

“Virtually all the growth in the last 20-30 years has come from nickel laterite mines in Indonesia, the Philippines, New Caledonia etc. The sulphide reserves globally have been quite static, the only major new sulphide operation to come on stream has been the Voisey’s Bay deposit in Canada,” he said.

“Since then most of the new sulphide mines that have been developed in WA, and elsewhere are basically replacing depleted reserves elsewhere.

“Same goes for Norilsk in Russia, they’re the big sulphide producers, they’ve been bringing on new mines to replace mines where the grades have declined, or they’ve shut down mines. In Canada, the same. And BHP, you know, is also fairly static in terms of its total production.”

Lennon expects the maximum growth from nickel sulphides based on known discoveries will be 150,000-200,000t, leaving laterites to make up the other 2Mt of projected growth in the battery and stainless steel market.

In terms of the battery market the other constraint is smelting capacity, given processes to produce precursor directly from nickel concentrate are yet to be commercialised.

“Nobody has successfully demonstrated that you can make nickel sulphate directly from a sulphide concentrate without going through the conventional processing routes,” Lennon said. “So that’s the challenge for the sulphide – the potential smelter bottleneck.”

Non-Chinese supply chain

While he doubts nickel sulphides will get an “ESG premium” as some miners have suggested, Lennon does think product sulphide miners outside Indonesia will be highly sought after by Western companies looking to form a battery supply chain outside China.

The Middle Kingdom currently accounts for 85% of the battery materials supply chain, something of deep concern to carmakers like Tesla, Ford, Volkswagen and Renault.

“There’s definitely a preference if you’re a Tesla, or a VW or Ford or whatever, to diversify away from exclusively Chinese sourced material,” Lennon said.

“So, you know, definitely BHP is getting no pushback at all in signing long term contracts. You know, because they’re another source of nickel.”

Poseidon’s Harold, whose company owns one of the few nickel mines in the rich Kalgoorlie-Kambalda region not currently contracted to sell concentrate or ore to BHP’s Nickel West business, says interest has come from near and far for nickel from Black Swan.

“We’re seeing significant interest from the traders, traditional smelting companies and also we’re seeing new entrants to the market being the likes of the OEM car manufacturers,” he said.

“You’ve seen Tesla doing the deal with BHP but we’re also seeing battery manufacturers talking to us too about taking long term contracts. They can’t treat the concentrate but they can act as an intermediary between the smelter and ourselves.

“Everyone is trying to secure nickel units at any stage in the production process. That’s a change that’s new to me and I’ve been selling nickel concentrate for 30 years.”

Harold said Poseidon also had an MoU with Pure Battery Technologies, which is looking to build a precursor plant in Kalgoorlie by 2024.

Having lived through the 2007 boom, when prices hit US$54,000/t and BHP’s Nickel West division generated higher profits than its iron ore mines, Harold believes the combination of EV demand and supply disruptions will support higher nickel prices.

“I think we’re heading into a much higher nickel price environment, where we are today and above,” he said.

“(There could be) supply disruptions which lead to even higher prices a la what happened with iron ore pricing when they had the problems in Brazil with the tailings dams.

“I think we’re heading into one of those environments for nickel, how long it last for I don’t know, but my sense is we are talking about … some years of much higher nickel prices and I think that’s pretty consistent with what the analysts are forecasting.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.