Glencore has some stunning figures on the levels of battery metals the world will need by 2050

Pic: Bloomberg Creative / Bloomberg Creative Photos via Getty Images

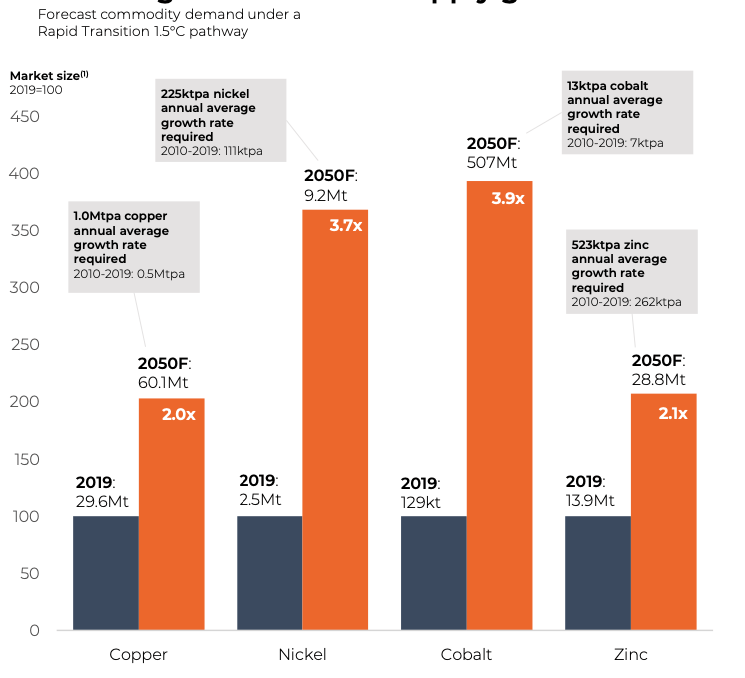

- Global demand for copper and zinc to double by 2050, increase four-fold for cobalt and nickel

- ‘To meet this global demand for metals, we will have to increase supply, but there isn’t a large pipeline of new mines coming into the system’ – Glencore

- Mining industry faces challenge to meet forecast demand with new mines in difficult geographies and a small projects pipeline

Commodities producer and trader Glencore has put some bold numbers on the volumes of battery metals needed to supply the world as its moves away from fossil fuels usage.

The London-listed company has modelled the quantities of cobalt, copper, nickel and zinc required as the world embraces electric cars and greener electricity generation.

“The transition to a low-carbon future is overall positive for Glencore in view of our commodity mix,” Glencore chief executive, Ivan Glasenberg, said in a transcript of his talk this week to analysts for the company’s 2020 financial results.

Glencore has modelled the effect of expected changes in global demand for cobalt, copper, nickel and zinc from 2020 out to 2050 under a rapid decarbonisation scenario.

Forecast growth rates and quantities of demand for these commodities are stunning, and is hottest for cobalt and nickel at nearly four times current levels.

Glencore’s scenario for future battery metals demand flows into the narrative of a new commodities super cycle spoken about by investment banks Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

Copper and zinc demand to double

Copper demand is expected to rise to 60 million tonnes by 2050, which equates to double today’s consumption volume of about 30 million tonnes per year, said Glencore.

“Therefore, we will have to produce an extra 1 million tonnes of copper per annum going forward from 2021 to 2050,” said Glasenberg.

Producing this much additional copper will be a challenge for the mining industry which only increased its production volume by 500,000 tonnes per year from 2010 to 2019.

“So we are going to double that to meet the demand for copper going forward with this transition to different forms of energy,” he said.

For zinc, current global demand is running at 13.9 million tonnes per year, and this will likely increase to 28.8 million tonnes per year by 2050, according to Glencore’s numbers.

“And we will have to grow by 500,000 tonnes per annum as opposed to around about 260,000 tonnes,” Glasenberg said.

Global cobalt and nickel demand

Moving to two other battery metals, cobalt and nickel, their demand profile is forecast to be four times higher than current levels, said Glencore’s chief executive.

“Today, the world consumes around 130,000 tonnes of cobalt per annum. And by 2050, we’ll be consuming about 507,000 tonnes per annum,” Glasenberg said.

“A large amount of that is put in the batteries for electric vehicles. And the growth of electric vehicles going forward will demand a lot more cobalt.”

Glencore only managed to produce an extra 7,000 tonnes per year of cobalt from its production base in the central African nation of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The company is the largest producer of cobalt in the world at 27,000 tonnes per year, and is planning to increase its cobalt production to 40,000 tonnes per year.

“To give you an idea there, it also tells you that we’ll have to produce an extra 13,000 tonnes of cobalt per annum to meet that target,” he said.

For nickel, the annual production increase required between now and 2050 is around 225,000 tonnes, twice the achieved production rate of 111,000 tonnes over the past decade.

“Today, the world consumes around 2.5 million tonnes of nickel. We’ll have to go up to 9.2 million tonnes by the year 2050, 3.7 times the amount consumed today.

“So we really have got to double production every year going forward,” Glasenberg said.

Projects pipeline and mine investment is starting to lag behind

“And therefore, the world’s mining industry is going to have to find ways to increase production,” said Glasenberg.

Therein lies a challenge for the mining industry, as it has struggled in global terms to increase production, as it moves to more difficult geographical areas.

“The new mines are in challenging locations, lacking infrastructure. But these are the areas where we are going to have to go and that is where the new mines will have to come, in these more difficult regions, so it is going to be a lot harder,” he said.

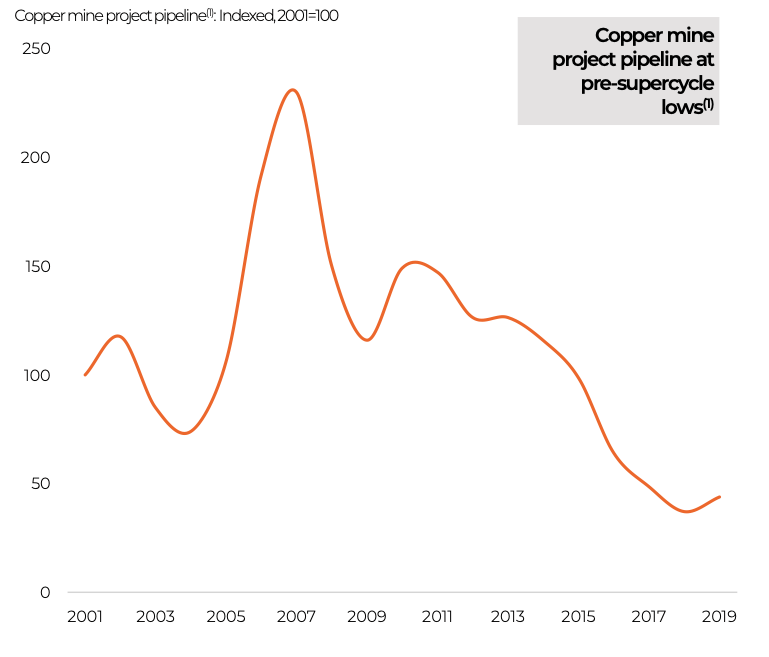

Also, the industry’s pipeline of new mining projects is much lower now than in the early 2000s when China was just starting its industrialisation and urbanisation.

“There was a lot more capital expenditure in the mining sector when it ramped up during 2005, 2007, it has come down considerably now,” said Glasenberg.

To illustrate his point, he included in his slide presentation a graph showing the projects pipeline for new copper mines over the past 20 years.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.