Explainer: Why are so many explorers chasing a porphyry payday?

Pic: Getty

When it comes to porphyry deposits, size counts.

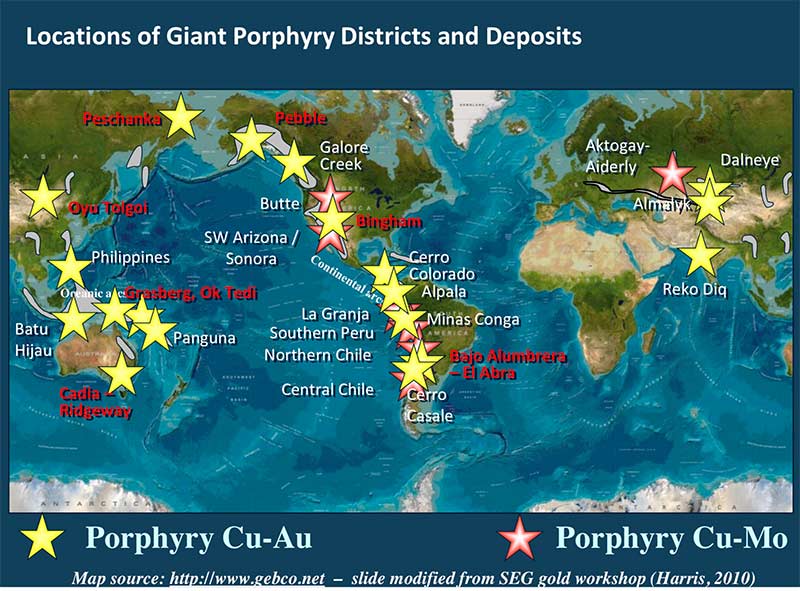

These multigenerational monsters are responsible for ~60 per cent of the world’s copper, most of its molybdenum, and significant amounts of gold and silver.

Their easy-mining large volumes make up for the low grades, typically between 0.3 per cent to 1 per cent copper equivalent.

But these company makers come with their own challenges, especially for small cap explorers.

Geologist Dr Steve Garwin is one of the world’s foremost porphyry experts.

He has been involved in several exploration and mining projects, including the Batu Hijau copper-gold porphyry copper deposit in Indonesia and the discovery of the world-class Alpala porphyry deposit in Ecuador.

Porphyries are often perceived as ‘capital intensive projects’ due to the billions of dollars required to get them up and running, Garwin says.

Exploration is expensive, often requiring numerous deep, very expensive drill holes into ‘blind’ exploration targets hidden under cover or at great depths.

That alone can be a challenge for most cash strapped junior companies. And that’s before development even starts.

“These can be company makers, but are large-scale mining operations — anywhere between 20 to 50 million tonnes of per annum,” Dr Garwin told Stockhead.

“This is a big earthmoving exercise.

“It’s not uncommon to spend $US3bn ($4.6bn) to set up these mines, be they open pit or large-scale block cave underground operations.”

And yet juniors — despite the high cost of resource definition (drilling) and development – have been making many of the porphyry discoveries over the last ~20 years, Dr Garwin says.

“The Newcrests, BHPs, and Rios of the world behave like Big Pharma companies; they’ll pick several juniors and back them,” he says.

“Even if one in 10 plays come in that’s a win.”

SolGold’s (LSE-SOLG and TSX-SOLG) Alpala project is by any definition a Tier 1 world-class deposit – 10.9 million tonnes of copper, ~24moz of gold and 100moz of silver.

This $328m market cap company is heavily backed by both Newcrest Mining (ASX:NCM) and BHP (ASX:BHP).

Apala’s estimated $US2.7bn development capex is actually on the cheaper end of the scale.

Rio’s gigantic Oyo Tolgoi underground mine in Mongolia will cost nearer to $US8bn once completed, while new producer First Quantum spent $US6.7bn to get its Cobre Panama mine up and running.

But the potential payday is huge. These mines produce a lot of metal, and make a lot of money, over a long period of time.

SolGold’s Apala could yield over $US70bn worth of payable metal over its 55-year life, which includes an estimated 207,000t of copper, 438,000oz of gold and 1.4moz of silver in concentrate per year for the first 25 years.

And that’s nothing on Rio Tinto-owned Kennecott, which has been mining the Bingham Canyon pit in the US since 1903.

The ~1km deep, 4km wide open pit remains one of the top mines in the world, producing about 300,000t of copper, 400,000oz of gold, 4moz of silver and 30 million pounds of molybdenum every year.

Just check out the size of this thing:

A ‘nearology’ rush is underway

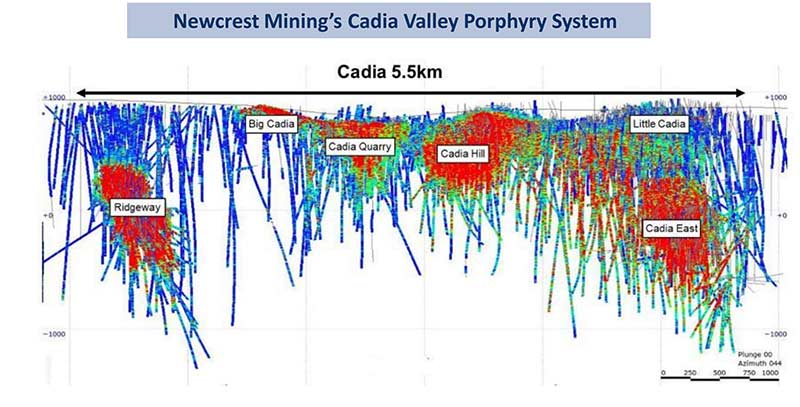

Right now Cadia Valley and Northparkes in NSW are the only two copper-gold porphyry mines in Australia.

In recent years major miners like Sandfire, Freeport and Fortescue have been pegging ground on the so-called Lachlan Fold Belt, a zone of folded/fault rocks of similar age which dominates NSW and Victoria, searching for the next Cadia.

This massive, super low-cost operation currently produces nearly 913,000oz of gold and 91,000 tonnes of copper every year.

But investor attention has been sparked more recently by two important discoveries.

In September, Alkane Resources (ASX:ALK) hit thick porphyry copper-gold at the Boda prospect, about 110km north of Cadia.

Later that same month, Stavely Minerals (ASX: SVY) made a huge copper discovery at its namesake Victorian project, also part of the Lachlan Fold Belt.

Results from the Thursday’s Gossan prospect revealed a monstrous shallow, very high-grade intersection — which included a ‘stunning’ 2m intersection grading 40 per cent copper, 3g/t gold and 517g/t silver.

The potential for a bulk-tonnage porphyry copper-gold system at depth remains a potential prize.

For Stavely and Alkane — and a few of their small cap neighbours — these were share price re-rating events. Now there’s numerous explorers searching for the next big porphyry discovery.

In the Lachlan Fold these include Impact Minerals (ASX:IPT), Krakatoa Resources (ASX:KTA), Magmatic Resources (ASX:MAU), Emmerson Resources (ASX:ERM), Alice Queen (ASX:AQX), DevEx Resources (ASX:DEV), Talisman Mining (ASX:TLM) and Carawine Resources (ASX:CWX).

Recent ASX debutants Kaiser Reef (ASX:KAU) and Godolphin Resources (ASX:GRL), also in the Lachlan Fold, both performed pretty well on listing.

Then overseas, there’s early stage explorers like Gold Mountain (ASX:GMN) in PNG, as well as more advanced players like Sunstone Metals (ASX:STM) in Ecuador and Hot Chili (ASX:HCH) in Chile.

NOW READ: The hunt is on for the next big porphyry discovery in the Lachlan Fold Belt

What should punters look for in an advanced, ‘post discovery’ project?

For starters, some jurisdictions can be a real risk for potential operations of this size, cost, and longevity.

Panguna, on the Pacific island of Bougainville, was the world’s largest open pit copper-gold mine when production halted in 1989 due to militant activity. It’s been closed ever since.

Panguna was operated by Bougainville Copper, a subsidiary of Rio Tinto which now calls itself BCL (ASX:BOC).

“They had enough years to make their money back, but they still left half the ore in the ground,” Dr Garwin says.

At a project level, Warren Potma, principal geologist at CSA Global looks for grades of at least 0.6 per cent copper equivalent, preferably more than 1 per cent copper equivalent.

He also says small porphyries (~50mt), typically a vertical pipe with a diameter up to 200m, “are hard to develop and make money on unless you have a good grade, or you have a cluster of these mineralised porphyries”.

“Large porphyries (~500-2,000Mt) can support lower grades through economies of scale and are the preferred target of the majors,” Potma says.

Supergene (near-surface) copper enrichment in the oxidised zone can be very important to project economics, Potma says, particularly for the copper-rich porphyry deposits.

“Potential upside opportunities in porphyry mineral systems also include the potential for multiple mineralised porphyry intrusions in the one area and other associated high-grade hydrothermal breccias and peripheral epithermal vein and skarn deposits,” he says.

But post mineralisation intrusions can be a significant economic issue in porphyry copper deposits.

“These intrusions ‘stope out’ (or replace) the mineralisation with unmineralised (waste) rock either diluting the average grade of the deposit or increasing waste rock mining costs.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.