Explainer: How to develop a gold mine – from exploration to production

Pic: Getty

Interested in junior gold miners but feeling left in the dark by jargon such as JORC codes, drill cores and volcanogenic massive sulphides? Here’s a guide to gold mine exploration and development to help you make sense of announcements on early exploration through to feasibility studies.

After securing its tenements from the relevant government authority, a company tries to find out if the property hosts a feasible gold reserve and narrow down its location.

Some tenements come with information from previous, or historic, mining activities. At other sites companies have to start from scratch.

Exploration begins

In initial exploration, regional scale geophysical surveys can include remote sensing (aeromagnetic surveys, satellite imagery and aerial photographs).

Magnetic surveying may also be used, including induced polarization which can identify the electrical chargeability of materials beneath the Earth’s surface, such as ore.

Additionally, exploration companies extensively use geochemical techniques to discover near-surface or covered gold deposits.

Small samples of soil are taken on an expansive grid to identify the gold, where the most common measurement is parts per billion.

This method can also be used when geologists want to sample the top of bedrock, which can be 20 or 30 metres below the surface.

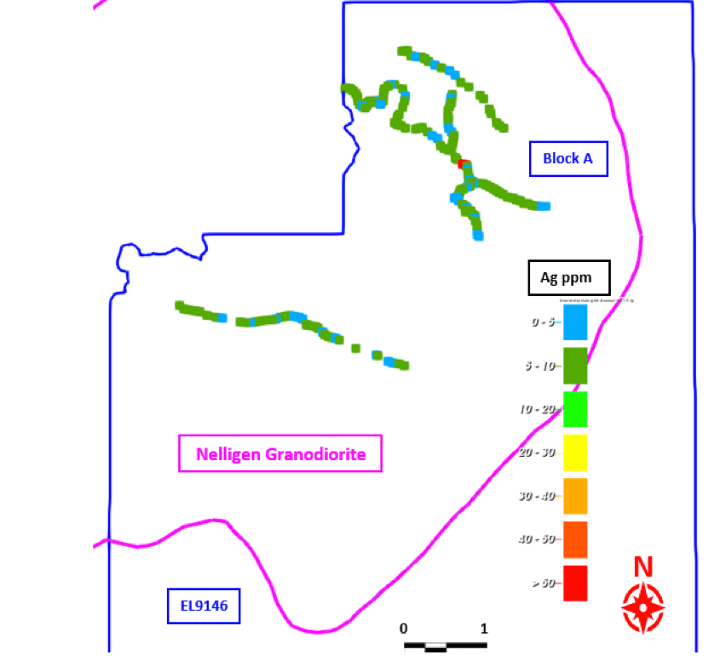

Geochemical exploration can also be done with portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) analysers. These hand-held devices can contribute to fast and effective field sampling such as that completed by Mitre Mining Corporation (ASX:MMC).

At its highly prospective Batemans project in the Lachlan Fold Belt of NSW, the company used pXRF readings to highlight key areas for detailed follow-up targeting gold, silver and rare earth elements.

Also, exploration companies extensively use geochemical techniques to discover near surface or covered gold deposits.

Small samples of soil are taken on an expansive grid to identify parts per billion of gold. This method can also be used when geologists want to sample the top of bedrock, which can be 20 or 30 metres below the surface.

Drilling down

Once at-surface exploration is carried out, drilling is then conducted to find out more about the grade, depth, length and mineral style of a deposit.

One of the most common methods deployed is reverse circulation (RC) drilling, which is done to extract bulk sample rock cuttings using hollow tubes and compressed air.

It’s followed up with diamond drilling, which yields smaller but more precise sampling and analysis.

The samples obtained from drilling, or drill cores, are sent to independent laboratories which return the assay results showing the composition of the ore body.

Companies sometimes also have assaying done on hand specimens collected from outcrops to spot check information collected from drilling.

Assays are carefully analysed not only for gold, but also for indicator minerals for clues that a gold reserve may be close by.

That’s why gold explorers’ drilling results often highlight the discovery of other precious metals such as silver, platinum and palladium, as well as arsenic, bismuth, mercury, copper, lead, zinc, cobalt, nickel, iron, tellurium, selenium and antimony.

It’s at this stage that announcements can refer to the discovery of an orogenic deposit, which have so far been the world’s main source of gold, and are formed from gold contained in fluid movements along tectonic plate boundaries.

Another important source of gold are intrusion-related gold systems (IRGS). These are generated by the collision of major tectonic plates and are therefore found mainly on the ‘Ring of Fire’ around the Pacific Rim, including eastern Australia.

A recent study undertaken by Laneway Resources’ (ASX:LNY) at its Agate Creek project in North Queensland highlighted strong potential for an IRGS in the style of the nearby former Kidston mine, which was once Australia’s largest open cut gold mine.

Also rich in gold – as well as silver, copper, zinc and lead – are volcanogenic massive sulphide (VMS) deposits which in turn contain massive sulphides or semi-massive sulphides often referred to in announcements.

Originating from undersea volcanoes, VMS deposits can have the potential for long-term mining thanks to the clusters of deposits, or ore lenses, close to each other.

Porphyry deposits supply a significant amount of the world’s gold and most of its copper.

They were created after large amounts of hot water carrying metals passed through rocks to form metal deposits.

The ancient movement of molten fluids from beneath the Earth’s surface can result in gold occurring as deposits called lodes, or veins, in fractured rock.

Is it feasible?

If preliminary exploration work indicates a mineral deposit, a company will work towards resource and reserve definition, followed by a feasibility study.

In Australia the system governing how companies report on their minerals exploration results, mineral resources and ore reserves is called the JORC code.

The code is developed by the Australasian Joint Ore Reserves Committee (JORC) to protect investors from misleading information.

The resulting feasibility study analyses information gathered in the exploration and resource definition phases to determine if the project is economically viable.

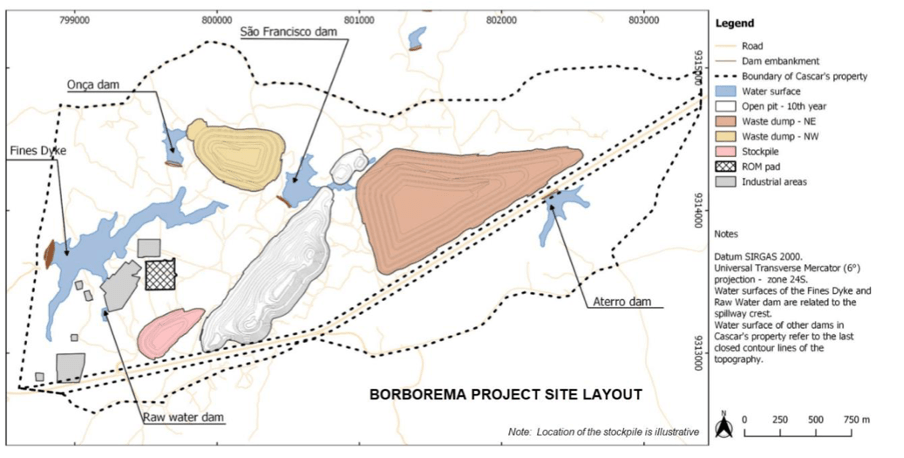

Water availability is essential to a mine’s feasibility and can significantly affect the scope of a project if ready alternatives cannot be accessed.

A recently completed water study at Big River Gold’s (ASX:BRV) Borborema project located in a semi-arid area of Brazil, for example, identified water management practices that combine limited site water resources with a nearby town’s grey-water sources. In turn, Big River advised that the expanded water source could support a doubling of forecast production from the already significant 2 million-tonne-per-annum (Mtpa) up to 4Mtpa.

A proper feasibility study has four key phases, each with more certainty represented by their levels of estimation accuracy:

- Scoping or conceptual study

- Pre-feasibility study (PFS)

- Definitive feasibility study (DFS)

- Bankable feasibility study (which has more detail for financiers)

If a company determines a project is feasible the next step is to move forward with the assessment and approval, or permitting, phase.

In the permitting phase, the mining company will present to the required agencies its Environmental Impact Study (EIS) that outlines the proposed possible environmental, economic and social impacts, and how these can be best managed.

The approval process in Australia takes an average of one to two years.

Blast off!

Once an exploration company has obtained all the necessary permits and approvals to develop a mine, the construction phase kicks off.

Construction generally takes a few years, depending on the mine location, the size of the development and the regulations in the relevant region.

An open pit (or surface) mine is used when the ore body is up to a depth of approximately 400m. Otherwise an underground mine will be built, while some mines are a hybrid open pit/underground mine.

Identifying the transition depth for open cut to underground mining is a key challenge for mining engineers and requires detailed financial and design criteria.

If a mine is close to infrastructure, it may need only the facilities necessary for the mining and milling. During milling, crushers turn the ore into gravel-like consistency that is used in the next steps of gold processing.

Then, finally, after between five to 20 years of hard work (depending on the country and jurisdiction) and millions of dollars invested, a miner can start operating the mine and generate ongoing returns.

This article was developed in collaboration with Laneway Resources, Big River Gold and Mitire Mining, Stockhead advertisers at the time of publishing.

This article does not constitute financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any financial decisions.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.