Copper stores haven’t been this low in 47 years, driving prices to record levels

Pic: Bloomberg Creative / Bloomberg Creative Photos via Getty Images

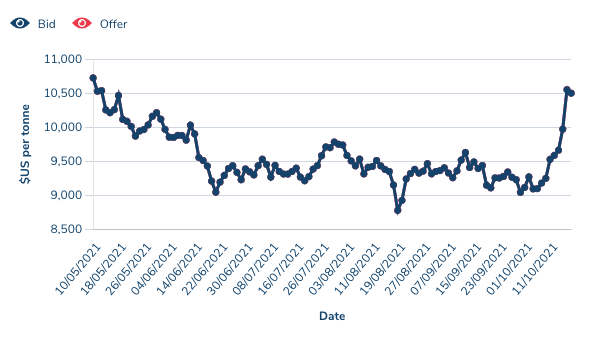

Copper is back in vogue after ending months of malaise to return toward record price levels on Friday, rising above US$10,000/t for the first time since May.

Prices fell 18% from the all time high of US$10,724/t seen on May 10 to just US$8775/t in late August before beginning their new run.

The close of US$10,538/t on Friday arrived amid a supply crunch across the base metals complex sparked by power rationing in China and Europe that has seen a number of smelters curb production.

That is around US$4.78/lb, up to 3-4 times the all in sustaining costs of large miners who at these rates are making extremely healthy profit margins.

The price pulled back yesterday and some analysts see the undersupply from South American mines that has fed into the copper shortage easing along with prices towards the end of the year.

But many in the industry remain buoyant, noting the long-term outlook for copper remains strong because of fading supply from legacy mines, historic underinvestment in exploration and the need for the highly conductive copper to feed the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy and electrification.

Glencore is bullish on the prospects we will continue to see records, predicting the price of copper will break the previously unseen US$15,000/t barrier this decade.

“I think everyone realises that the demand side is looking very bright over the next decade for EV minerals and particularly copper, which really has leverage to just about every technology and every renewable energy technology or new batteries technology out there,” said Andrew Sparke from ASX-listed copper explorer QMines (ASX:QML).

“So I think we’re in a really exciting sort of new, I dare to say, bull market.

“A long term structural bull market and so it wasn’t surprising that we’ve started to see a rise into the end of the year, based on this tightening supply side and strong demand.”

The cupboard is bare

When producers aren’t delivering the goods, downstream industries rely on warehouses in places like Shanghai, London, Singapore and Portland to source materials from commodities exchanges.

There’s a problem for them now though – the cupboard is practically bare.

As the world’s leading refined metals experts and traders came together for the annual LME Week last week, stocks of the red metal on the London Metals Exchange sunk to their lowest since 1974.

The last time the LME ran this low on copper, Barbra Streisand’s The Way We Were was the top selling single in America. Gough Whitlam was our PM.

A rush for product has also seen extreme backwardation, with desperate consumers offering US$350 more for metal now than metal to be delivered in three months’ time, the more commonly traded contract in most base metals.

Morgan Stanley: Copper inventories continue to draw down – on the LME, available stocks (adjusted for cancelled warrants) are at the lowest since 1974 pic.twitter.com/85r9LHXEV4

— Martin Turenne (@MartinTurenne) October 18, 2021

Former Goldman Sachs analyst and CEO of ASX-listed copper explorer Kincora Copper (ASX:KCC) Sam Spring explained how rare this situation was.

“(There’s been a) real tightening in the fundamentals of the market, which I guess, you’ve got a balanced market now,” he said.

“And a number of sort of energy crises or shipping and logistics crises that are taking place with a number of sort of ongoing tax and legislative concerns regarding Peru and Chile. And that’s impacting some of the production and some delays to some of the existing projects.”

The other side of the equation is demand. While demand for copper dropped into a hole when the Covid-19 pandemic hit, sending prices back in the direction of US$2/lb, massive infrastructure spending first in China and then across the world drove it back to record levels in May.

Going forward though, it is the increased electrification of the world and growing markets for renewables and EVs that is expected to send demand even higher than it is today, with few large scale copper mines in the pipeline to service it.

“So it’s a really interesting landscape. What does it sort of mean bigger picture?” Spring said.

“I think that sort of fundamental outlook of what is in the pipeline, just rises to the surface again.

“The outlook a few years from now probably looks even more favorable as long as the demand side continued to hold strong.”

Mines are getting older, tired

To Sparke, copper is such a good investment because it “has leverage to just about every technology”.

There is a general acceptance that we will need new, large scale copper mines to keep the industry running in its transition to becoming a battery metal.

While the world has for decades relied on the giant copper porphyries pockmarking South America’s Andes mountains from Chile to Peru, there is always an economic and social limit to how far mines can run.

“When you look at the supply side, you see very constrained copper supply, particularly out of South America, Chile and Peru, which is give or take sort of 35-40% of the market,” Sparke said.

“When you sort of peel back the onion and look at a lot of those mines, they’re getting older and more tired and they’re a long way up in the Andes, so they’re very high altitudes, and have issues with water and power and had some labor issues.

“So I think this is going to be a continued theme over over the next couple of years.”

Are high prices a bad thing in the long run?

A commonly used phrase in the mining industry is that the cure for high prices is high prices.

In other words, when prices exceed what customers are willing to pay they will either start a buyer’s strike in an attempt to crash them (cf. iron ore), or if they can, replace your product with a cheaper ingredient.

It has been suggested copper could be subbed out for cheaper and more abundant aluminium (a metal also seeing 13-year highs off the back of smelter shutdowns in Asia).

Spring is not so sure this is possible. A big shift to aluminium would mean increasing the world’s reliance on its most power-hungry industry, a bad move in a world currently absorbed with the challenge of fighting global warming.

“One thing people often ask is, what about demand destruction to the copper price if you do see this theme playing out?” he said.

“You have a look at how power intense that is and if you’re driving towards decarbonisation, if you’re moving towards more aluminium you’re needing more power to use less power, if you know what I mean.

“So it’s one of those areas that I think demand destruction for copper is probably not as strong as what you’ll see for a number of other base metals.”

Big boys betting on copper

A sense of where copper may be heading has been the increased interest of the world’s biggest miners in the commodity.

While BHP (ASX:BHP) and Rio Tinto (ASX:RIO) have always been into copper (they co-own the giant Escondida mine in Chile among others) each have made it a more prominent part of their exploration and development portfolios in recent years.

Rio is set to open the new Winu mine in WA’s Paterson province around 2025, while BHP has a new discovery near its world class Olympic Dam copper-gold-uranium mine in Oak Dam in South Australia.

It yesterday revealed it would start an exploration JV to explore the neighbouring tenements with unlisted explorer Red Tiger Resources, while it is also part of a $25m exploration farm-in over tenements owned by junior Encounter Resources (ASX:ENR) in the Northern Territory.

Gold miner Newcrest (ASX:NCM) has big plans to make its copper exposure its point of difference among the major gold stocks, with plans to increase copper production by 37% to 175,000tpa by 2030 even as its gold production remains stagnant.

Newcrest and BHP have called a ceasefire in recent times, but are both on the register of Ecuadorean copper explorer Solgold and the growing demand for the red metal could awaken a dormant takeover tussle between the mining giants.

“It is a favorable environment there and you can have a look at Solgold where you’ve got BHP and Newcrest both on the register and that creates a bit of a competitive tension there,” Spring said.

“The reality is, if you find a copper porphyry, which is the mineral system that supplies the most amount of copper around the world, the big projects, they’re capital intensive, they’re long lead times.

“Generally, you do see the junior end up with a bigger brother or two on the register. And I guess it is more favorable from your existing shareholders’ perspective to have competitive tension for those conversations.

“It seems at least for the moment that most of the majors are increasing their footprint with exploration and trying to grow their existing project pipeline, (but) you’re starting to see a little bit more M&A coming through like South32, for example last week (paying US$1.5b for a stake in a Chilean copper mine).”

Porphyries dominate but is VMS a decarb play?

Both listed this year, Kincora and QMines are different beasts.

Kincora is hunting major porphyry copper and gold occurrences in its land-holding in the Macquarie Arc of the Lachlan Fold Belt, surrounded by legendary porphyry discoveries like the Northparkes mine and Cadia-Ridgway.

QMines meanwhile owns four copper projects, including the Mt Chalmers mine near Rockhampton in Queensland.

It is a historic volcanogenic massive sulphide deposit mined from 1898 to 1982, containing 3.9Mt at 1.15% copper, 0.81g/t gold and 8.4g/t silver for 73,000t of copper equivalent at 1.87% Cu.

A resource upgrade is expected in the December Quarter. VMS deposits like Mt Chalmers tend to be smaller than porphyries but higher in grade, meaning as a general rule they are likely to be less power intensive.

“The higher the grade you’re mining obviously you need to produce less tonnes and therefore you’ve got less energy going into comminution, grinding and processing,” Sparke said.

“So these higher grade ore bodies like like you see at Mt Chalmers I think are going to come more into favour.

“I think investors are going to fund mines that show very strong economic and very strong returns to shareholders but also mines that can demonstrate that they are using less power and can develop these assets more sustainably.”

While the price of copper now is not necessarily as relevant for explorers, who will take a while to get their projects into production, it will bring money into the sector.

“If you find something, the time to drill it out and do studies means that the copper price today doesn’t have too much of a bearing by the time you’re actually financing the project or in production,” Spring said.

“But the key thing is sentiment and you are seeing an increase in dollars going into the ground in the copper space, because there’s increased realisation that there’s not a huge amount of new projects out there.

“I think from Kincora’s perspective of looking in Australia’s foremost porphyry belt … where you’ve got Cadia and you’ve got Northparkes, and a number of these big porphyry systems that are well recognised, I think you certainly will be well rewarded (for exploration success).”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.