Bawdwin, the mine that Hoover built, is about to get a new life

Pic: Bloomberg Creative / Bloomberg Creative Photos via Getty Images

Special Report: Three years ago junior explorer and mine developer Myanmar Metals (ASX:MYL) acquired a majority stake in one of the greatest metal deposits in history. In 2020, the 1000-year-old Bawdwin polymetallic mine is accelerating towards a big-time revival.

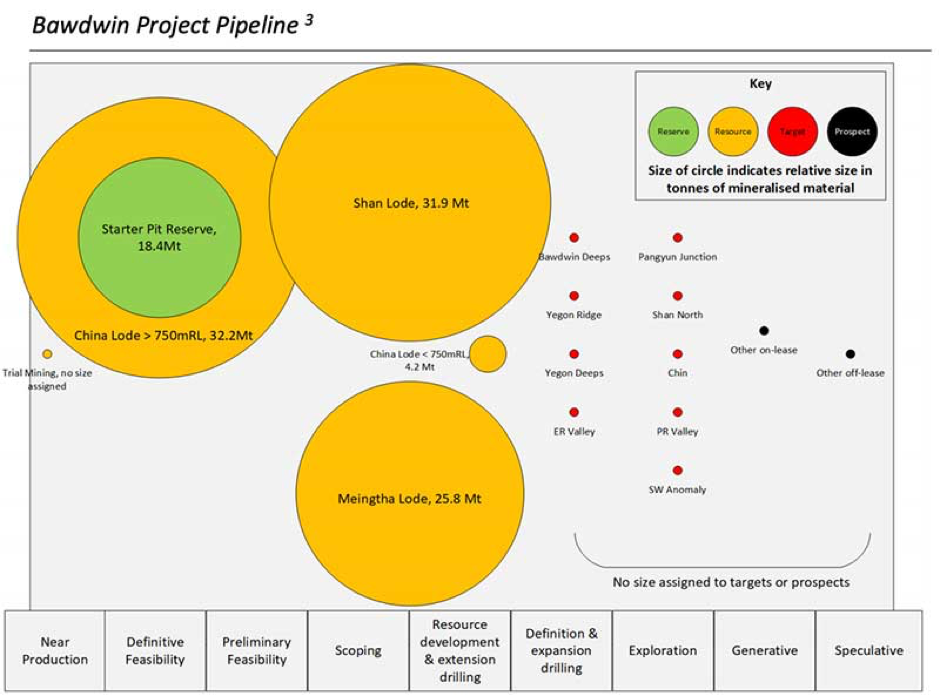

In less than three years Myanmar-based MYL has established a 101-million-tonne (mt) JORC resource grading 4 per cent lead, 3.1 ounces per tonne (g/t) silver, 1.9 per cent zinc, and 0.2 per cent copper from scratch.

The Bawdwin joint venture (Myanmar Metals 51 per cent) is now positioned to restart this globally important mine, with construction due to kick off later this year.

When production begins in late 2022 Bawdwin will be the world’s #3 lead producer and a top-ten silver producer, over a potential mine life spanning many decades.

This thing is huge, essentially a “dead ringer” for South32’s (ASX:S32) Cannington mine in Queensland, Myanmar Metals chief exec John Lamb says.

The central part of the Bawdwin mineralised system is about 2km long, 400m wide, and remains open in all directions.

“MYL has applied for a 50-year mining lease on the basis of studies completed so far,” Lamb says.

Bawdwin: an incredible history

Bawdwin in the northern Shan state of Myanmar means ‘silver hole’ in the local language. It’s believed the original Shan kings were mining Bawdwin for silver +1000 years ago.

In 1420, the Chinese arrived and took control of the Bawdwin region and the mine for the next few hundred years.

In the 1800s the British landed and took over, developing Bawdwin into a world-class (at the time) polymetallic mine.

A crucial figure here was Herbert Hoover —the soon-to-be 31st president of the United States. Bawdwin is the mine that made Hoover, then just a mining engineer, his fortune.

When Hoover saw Bawdwin he was so amazed he broke one of his own personal rules — never sink your own money into a company’s projects.

Hoover helped turned Bawdwin into the greatest mine in the British Empire. By the late 1920s this one underground mine was producing as much silver each year as the entire line of lode at Broken Hill in New South Wales. The thing was phenomenally big, in other words.

The mine was destroyed during World War 2. It was rebuilt post-war, but the British left Myanmar in 1948 and the mine was nationalised.

Production dropped off significantly and never recovered:

Caption: Bawdwin Lead, Silver and Zinc Production (1909 -1975)

For Myanmar Metals, it is crucially important that mining of this large-scale mineral system stopped just before the advent of high-volume modern mining in the mid-1950s.

“They were mining handheld tunnels, following the very high-grade metals – up to 50 per cent zinc-equivalent,” Lamb says. “It was all very high grade, low volumes.”

Projects that stopped production before the global mining industry got ‘big’ in the mid-50s are often largely preserved.

“And that’s what we are seeing at Bawdwin,” Lamb says.

“The British mined about a quarter of the known resource, which we haven’t finished defining.”

Creasy’s magic touch

Myanmar Metals was originally put into the project by famous prospector and major shareholder Mark Creasy.

Creasy has been investing in Myanmar for 20 years now, Lamb says. He’s actually a part owner of the country’s only zinc refinery.

But Myanmar was a military dictatorship for many years, Lamb says. It’s only in the last decade or so that democratic government has been established, and by this point the world had pretty much forgotten about Bawdwin.

Creasy, a friend of Lamb’s, is a “mining industry tragic”, with a private library that rivals the Hoover collection in the US for size and depth.

“He had all the back issues from the Indian geological survey where they reported on Bawdwin. He had memoirs from Hoover and all the other people who wrote on Bawdwin,” Lamb says.

“He had done his research.”

About three years ago Creasy’s contacts in Myanmar let him know there was a possible deal to be done on Bawdwin for the first time in its history.

“He suggested we go and have a look – and he was right, there was,” Lamb says.

“Mark currently has about 12 per cent shareholding in MYL and is a very, very strong supporter.”

2020: ‘The big year’

The first 13 years of production at Bawdwin is called the ‘starter pit’. This thing just keeps going, Lamb says.

“We’ve now defined two further phases of open cut mining after the [$US300m] starter pit, which have been completed at a scoping study level – that’s decades and decades of mining and processing,” he says.

This is the big year. Very soon the company will lodge it’s MIC (Myanmar Investment Commission) application, crucial for any foreign company looking to build, own and operate an asset in-country.

Myanmar Metals estimates it will receive that permit sometime around mid-year. A final feasibility study, which is now largely complete, will be released soon after.

This will be Myanmar’s most important mine, Lamb says. The government is “heavily committed” to getting this thing through and permitted.

In the meantime, Myanmar Metals has also been working on its all-important finance and off take agreements.

“We have multiple parties — international metal trading houses, large corporates and others — in the data room right now,” Lamb says.

“We will finalise that process once the DFS is released. That then allows us to start construction at the beginning of Q4 this calendar year.”

This ~$80m market cap explorer has already proven itself capable of raising large amounts of money from investors.

“We’ve now raised about $65m on this project, really just through sale of shares,” Lamb says.

“For a $80m market cap company that’s pretty impressive.

“That’s another point – what should our market cap be? Our shares are worth a fraction of what they should be trading at, solely based on what we have defined so far.”

Bawdwin, which has proven itself bigger than Lamb initially thought, remains open in all directions. Successful exploration at Bawdwin and across the wider area is ongoing.

“We are laying decades and decades of mining and mineral processing out front of us,” Lamb says.

“Bawdwin is bigger than I had originally thought — but it’s definitely turning into the mine that I had hoped it would be.”

This story was developed in collaboration with Myanmar Metals, a Stockhead advertiser at the time of publishing.

This story does not constitute financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any financial decisions.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.