Battery metals shortages, upstart tech and Piedmont’s fight – the EV rollout still has major hurdles to overcome

Pic: Bloomberg Creative / Bloomberg Creative Photos via Getty Images

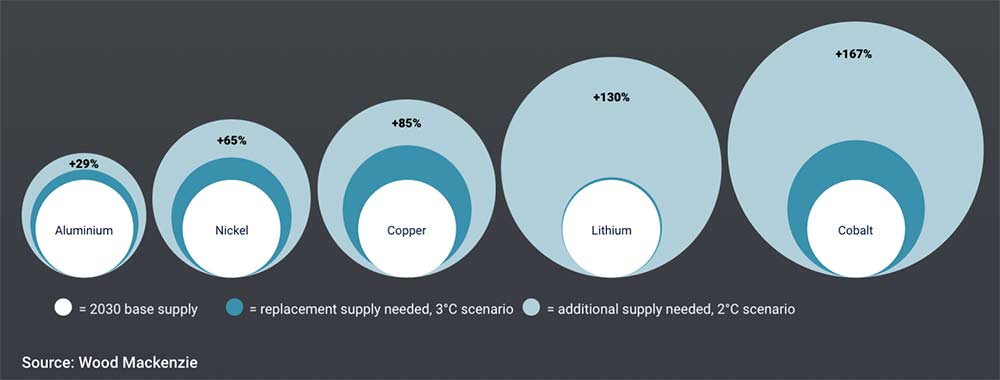

Impending battery metals shortages are all but confirmed by major analysts.

Take lithium. Benchmark Mineral Intelligence anticipates a forthcoming supply deficit to reach nearly 200,000 tonnes LCE by 2025.

In 2029 — even if Rio Tinto’s (ASX:RIO) gigantic $2.4 billion ‘Jadar’ project comes online — the lithium market will hit a deficit of 915,000t LCE.

This is a supply-demand gap more than twice as large as the entire lithium market in 2021, Benchmark says.

But it gets worse, because even those projects we assume are coming online are far from a sure thing.

Investors sometimes forget that mining is a dirty business.

Many communities don’t want it in their backyard, even if the result is a net positive for the global environment and the economy. Over the past few months, at least two advanced ASX-listed lithium players have hit serious environmental and jurisdictional obstacles on their way to development.

In the US, former market darling Piedmont (ASX:PLL) plunged nearly 20% after claims the company has repeatedly delayed seeking approval from Gaston County in North Carolina for its proposed lithium mine.

Five out of seven county officials allegedly now say they may block or delay the 30,000tpa lithium hydroxide project “because Piedmont has failed to inform them about the mine’s potential environmental impacts”.

Infinity Lithium’s (ASX:INF) chances of developing its 75% owned San José lithium project in Spain are looking similarly grim after the local government rejected an appeal against the recent denial of the project’s all important Investigation Permit Valdeflórez (PIV) research permit.

This isn’t a total surprise, as environmentalists and local residents appear to have been vocally opposed to the development for quite some time.

San José, the second largest JORC hard rock lithium deposit in the EU, was expected to produce 15,000 tonnes per annum lithium hydroxide over 30 years.

Miners and explorers in South America’s ‘Lithium Triangle’ – which contains about 75% of the world’s known resources – also face scrutiny.

“The Lithium Triangle is one of the driest places on Earth, which complicates the process of lithium extraction: miners have to drill holes in the salt flats to pump salty, mineral-rich brine to the surface,” according to the Harvard International Review.

“They then let the water evaporate for months at a time, forming a mixture of potassium, manganese, borax, and lithium salts that is then filtered and left to evaporate once more.

“While lithium extraction is relatively cheap and effective, it begs the question of sustainability and long-term impact.”

It explains why new ‘environmentally friendly’ extraction techniques – like those championed by lithium stocks Lake Resources (ASX:LKE) and Vulcan Energy (ASX:VUL) – are gaining traction with the market.

LKE, VUL share price charts

For miner and explorers, the risks are significant

Minelife analyst Gavin Wendt says the world has made the decision to switch to ‘clean energy’ before answering the question: ‘How do we actually access all of the vital materials we need to make it happen?’

“At a time when mining is becoming more difficult, we will dramatically and exponentially need to crank up mining worldwide in order to mine the resources that will facilitate EVs and the infrastructure necessary to create the energy for them to function,” Wendt told Stockhead.

“Environmentalists cheering the demise of the ICE vehicle and the move away from oil will be horrified by the environmental consequences of the massive increase in surface mining that will take place around the globe to power EVs, along with building their charging infrastructure and electricity distribution networks.

“The sheer scale of metals that will be required is mind boggling. What we are doing is potentially swapping one lot of environmental consequences for another.”

Some of the metals we need are concentrated in certain jurisdictions, which can present its own set of problems.

Take copper, for example. Chile and Peru together constitute close to 40% of world production, which is roughly the share of what is known as OPEC+ in terms of oil production, Wendt says.

“And that concentration is only going to increase, with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) expected to shortly overtake China as the No 3 producer,” he says.

“Lithium supply is also concentrated at present in the hands of a few major players, not all of them first-rate locations from a risk perspective.

“The political aggressiveness of leaders in these jurisdictions could be exacerbated by the market supply power that they have within their grasp.”

What happens if these battery metals projects aren’t built?

George Miller, analyst at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, says these regulatory situations speak to the difficulty of bringing a critical mineral mining project through to production.

“With both projects [Piedmont, Infinity] situated within electric vehicle end-markets, we can see that despite the end-goal of the electric vehicle value-chain to reduce emissions, local and regional governments and stakeholders may not necessarily be mining-friendly and can have issues with the externalities of the upstream of the supply chain,” he told Stockhead.

“Fortunately, the supply chain is putting its eggs in plenty of baskets, with investment now beginning to feed through to nascent lithium projects worldwide, as the supply chain awakens to a forthcoming lithium supply deficit.

“Some of this investment is close to end-markets and may face more regulatory hurdles before we see commercial supply, yet other investment is into projects in mining-friendly jurisdictions.

“The more we see of both kinds of investment, as we are now, the more likely something will stick and we will see more, crucially needed, supply reach the lithium market.

“Regardless, we anticipate a forthcoming supply deficit for lithium in light of mounting demand for electric vehicles, set to reach nearly 200,000 tonnes LCE by 2025 – these regulatory hurdles will only exacerbate this deficit situation.”

Emphasis ours. But warranted.

‘The cure for high prices is… high prices’

WoodMac analyst Simon Morris says these deficits are not necessarily a positive for incumbent producers and other near-term developers in the long term.

“Those with a vested interest in metals are already enthusiastic cheerleaders for an intoxicating narrative about the energy transition and the quantum of metal that will be needed to achieve it,” he writes.

“Producers are being courted by politicians, entrepreneurs, consumers and investors alike.

“However, whipping up a frenzy over the dizzying levels of additional metal that will feed the energy transition over the next 20 years – 360 million tonnes (Mt) of aluminium, 90 Mt of copper and 30 Mt of nickel under our AET-2 scenario – could prove a Pyrrhic victory.”

As the says goes, the cure for high prices is … high prices.

“If EV manufacturers, operating with inelastic retail prices and tight inventories, cannot guarantee access to critical metals at an affordable – and predictable – price, they will look to innovate or thrift them out to the greatest extent possible,” Morris writes.

“And there is a plethora of emerging technologies – such as next-generation electrofuels, polymeric energy storage and low/zero nickel- and cobalt-free, high-energy-density batteries – that could dramatically alter the clean-energy landscape.

“In doing so, they may push those metals expecting to benefit from the impending supercycle into obscurity.”

Or even… sodium ion?

Tesla battery supplier CATL unveiled a sodium-ion battery, a type of lower-density cell that uses cheaper raw materials than batteries made from lithium-ion metals https://t.co/JT5ZlAcvky

— Bloomberg Markets (@markets) July 29, 2021

As the supply challenge materialises, the inexorable rise in prices will surely incentivise alternatives, Morris says.

“The metals and the technologies they enable, seen as the platform for the first stage of decarbonisation, may not last the course as other, cheaper, more reliable alternatives break through.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.