Battery metals could rival oil in a Net Zero world: IMF

Pic: Schroptschop / E+ via Getty Images

Decarbonisation policies could see battery metals rival the oil and gas industry, with the IMF saying a Net Zero by 2050 scenario would more than quadruple the revenues generated by copper, nickel, cobalt and lithium companies over the next two decades.

In a special feature of the latest World Economic Outlook by the International Monetary Fund, IMF analysts say under ambitious climate reduction targets the battery metals complex could generate around US$13 trillion in revenue between now and 2040.

That would rival the oil industry and fall just US$6t short of the fossil fuel sector as a whole, signalling a radical shift in the industrial might of base metals producers.

Between 1999 and 2018 fossil fuel companies amassed a collective US$70t in revenue, against just US$3t for copper, nickel, lithium and cobalt, most of it by companies mining the red metal.

“In the Net Zero by 2050 emissions scenario, the demand boom would lead to a sixfold increase in the value of metal production — totaling $12.9 trillion over the next two decades for the four energy transition metals alone, providing significant windfalls to producers,” the IMF’s report authors said.

“This would rival the potential value of global oil production in that scenario.”

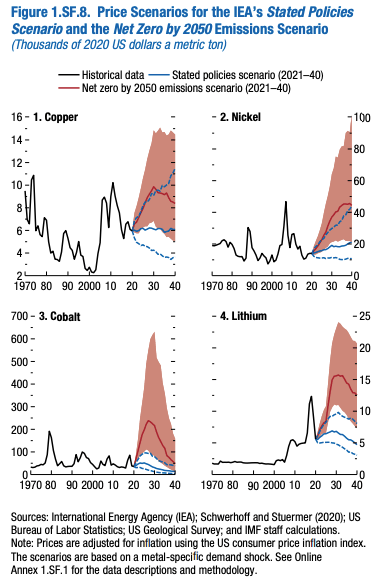

The IMF says price shocks caused by the rapid pace of change required in a Net Zero by 2050 scenario could see them “reach historical peaks for an unprecedented, sustained period.”

Who stands to benefit?

As the world’s dominant raw lithium producer and boasting some of the largest reserves of all four battery metals, Australia would have a competitive advantage in this economic transition, alongside copper rich nations like the DR Congo and Chile.

Australia’s GDP is heavily reliant currently on its exports of iron ore, gold, coal and natural gas.

But battery metals exporters would see huge benefits in the ambitious International Energy Agency Net Zero by 2050 scenario as global production of energy storage facilities and electric vehicles booms.

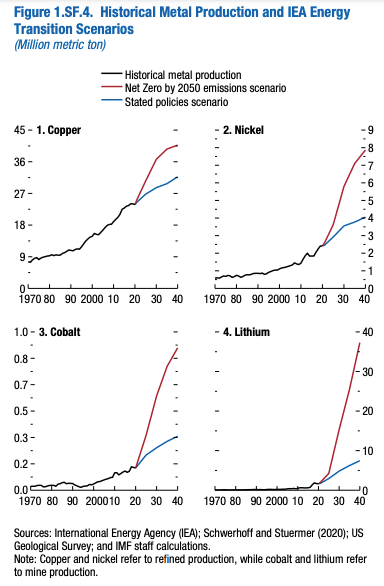

In that hypothetical future the world’s consumption of lithium and cobalt would rise by a factor of more than six, copper consumption would double and nickel demand would rise fourfold.

“The supply of metals is quite concentrated, implying that a few top producers may stand to benefit. In most cases, countries that have the largest production have the highest level of reserves and, thus, are likely prospective producers,” the report authors said.

“The economic benefits of higher prices for metal exporters could be substantial.

“Econometric analysis identifies the impact of price shocks, exploiting the different responses of GDP and government balances between the 15 largest metal exporters and importers.

“A 15 percent persistent increase in the IMF metal price index adds an extra 1 percentage point of real GDP growth (fiscal balance) for metal exporters compared with metal importers.”

Miners and explorers seeing increased mainstream interest

Peter Harold is the managing director of Poseidon Nickel (ASX:POS), which is aiming to restart its Black Swan nickel mine and concentrator near Kalgoorlie in WA.

Nickel prices are sitting around US$19,000/t today, some 250% above the early 2016 trough of US$7600/t and a price at which low cost operations are coming out of mothballs.

Harold said the IMF report was an example of the growing mainstream awareness of the need to increase nickel supply.

“I definitely saw the article and I’m very interested in the numbers on that,” he said.

“I’ve been sort of quoting in my presentations for a while now, the increase in demand for nickel that Glencore put out, from 2.5 million tonnes in 2019 to 9Mt in 2050.

“And that’s nearly a fourfold increase in demand. So I think now people are starting to sort of focus on this a bit … that this is potentially real.

“And as a result of that, I think there’s been renewed interest in the battery metals space clearly.

“So it’s very encouraging and clearly it’s going to happen, it’s just a matter of how quickly.”

Market diversifying away from traditional consumers

More than 70% of the market for nickel comes from stainless steel.

Traditionally a small producer like Poseidon would sell offtake to a larger company like BHP (ASX:BHP), which owns the integrated Nickel West refining business in WA, who would then supply steelmakers in Asia.

Now battery makers and EV dealers are in the market for refined nickel products as well.

Just this year Tesla inked a supply deal with BHP, Korea’s POSCO is buying a stake in the Ravensthorpe nickel mine and LG signed an offtake deal with junior Australian Mines (ASX:AUZ).

Poseidon expects to complete studies on the restart of Black Swan, which has been shut since 2008, by around April next year ahead of financing.

Harold said inquiries about its future product had come from more diverse sources than when his previous company Panoramic Resources (ASX:PAN) transitioned from developer to producer in the mid-2000s.

“There’s definitely more players in the market now,” he said.

“Still the traditional smelting and trading companies are the primary discussions, but there’s lots of other groups that are popping their head up and making contact.

“There’s a lot of people trying to obviously secure nickel units, but obviously until we know exactly what we’re going to be producing and the volume it’s still a bit premature.”

Higher prices needed to induce supply

The IMF is one of a number of groups that has highlighted supply lags as a risk to the energy transition.

“To limit global temperature increases from climate change to 1.5 degrees Celsius, countries and firms increasingly pledge to reduce carbon dioxide emissions to net zero by 2050,” they said.

“Reaching this goal requires a transformation of the energy system that could substantially raise the demand for metals.

“Low-greenhouse-gas technologies — including renewable energy, electric vehicles, hydrogen, and carbon capture — require more metals than their fossil-fuel-based counterparts.

“If metal demand ramps up and supply is slow to react, a multiyear price rally may follow — possibly derailing or delaying the energy transition.”

This could see prices rise several hundred per cent on 2020 levels, with historical peaks being hit for sustained periods and are expected to peak around 2030 when construction of renewable energy hits its highs.

This would induce a supply reaction, the IMF says.

While nickel sulphide mines like Poseidon’s are likely to be viable at current prices or higher, a lot of new production needs to come from more difficult laterite ore sources, which use the capital intensive high pressure acid leach process.

“You will need higher prices for the (battery) commodities to entice more material into the market, there’s no question about that,” Harold said.

“Some of the projects that are around are major numbers if you’re talking about HPAL, and some of these other big projects.

“As a result, you know, you’ve got to have higher prices for longer, especially if the grades are getting lower.”

Poseidon taking a look at precursor supply

As well as exporting raw materials there could be ways for Australian miners to get a bigger slice of the battery pie.

Poseidon announced an MoU yesterday with privately owned Pure Battery Technologies to study the suitability of ore from Poseidon’s projects to supply a proposed 50,000tpa precursor cathode active material plant to be based in Kalgoorlie.

PCAM is an intermediate chemical which goes into batteries.

By selling a higher value product more of the supply chain value would be captured onshore and Australian miners could improve the revenues they receive for their end product.

While the MoU is still at a formative stage, Harold said downstream processing of battery materials made sense in Australia.

“If the investment dollars are available for investments like this, they should be built in places like Australia and especially Western Australia,” he said.

“It’s got the technical expertise to build these things, it’s got the right sort of political environment and it’s got a history from the mining side, and so it would be great to see more downstream investment here.

“And I don’t think that pure batteries are the only ones looking in the space.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.