Antimony: One of the most important critical minerals you’ve never heard of

Picture: Getty Images

- Antimony’s importance dates to WWII when its flame and heat resistant properties elevated this metalloid to hero status

- To this day, antimony is used right across the board in the defence industry for military applications

- But like most critical minerals, China dominates supply

Though high on the critical minerals list of many countries around the world – Australia, the United States, Canada, Japan, India, and the European Union – few people know much about antimony (Sb), how it’s used, or why experts consider it to be the most important mineral you’ve never heard of.

A silvery, brittle metalloid and rarely found in its native metallic form, it is usually extracted primarily from stibnite, containing 72pc antimony and 28pc sulphur, to form more than 100 different minerals.

The importance of antimony dates to WWII, where it holds a reputation as an ‘unsung war hero’ due to its flame and heat resistant properties, attributed to saving the lives of American troops.

During the war, an antimony-based fire proofing compound was applied to tents and vehicle covers to suppress the spread of flames while its metal strengthening properties played a critical role in the creation of tungsten steel and the hardening of lead bullets.

To this day, antimony is used right across the board in the defence industry for military applications including precision optics, night vision goggles, infrared sensors, military clothing, tanks, and the manufacture of armour piercing bullets.

Because of its fire-retardant properties, antimony is also widely used in plastics and paints, and its anti-corrosion properties strengthen everything from nuclear energy facilities to batteries and wind turbines.

High-tech devices like smartphones, semiconductors, cars and computers depend on antimony to operate efficiently.

According to experts, it is not only a key component of technology that powers modern economies – our current way of life depends on it.

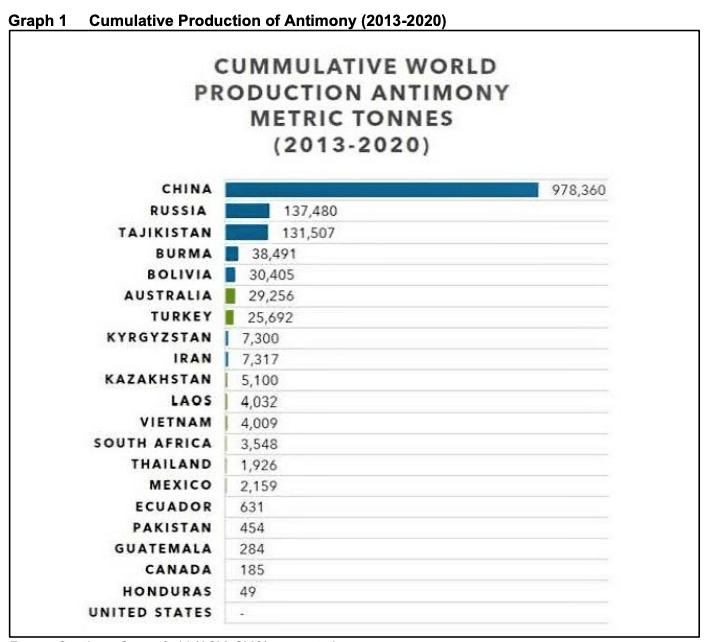

Where is antimony produced?

Like most critical minerals, Southern Cross Gold (ASX:SXG) managing director Michael Hudson says around 80% of antimony comes from China and Russia.

In terms of the top seven producing countries including the likes of China, Russia, Tajikistan, Burma, Bolivia, Turkey, and Australia, Australia produces a relatively small amount.

As mentioned in the US Geological Survey in 2021, Australia produced around 2,000t of antimony compared to China’s 80,000t and Russia’s 30,000t.

In fact, the Costerfield Mine in Victoria – owned by Canadian-based Mandalay Resources – is not only the seventh highest-grade gold mine and fifth largest producer of antimony in the world, but it is also Australia’s only antimony producer.

Production at Costerfield was 11,079 ounces of gold and 523 tonnes of antimony in the second quarter of 2022 versus 9,959 ounces gold and 858 tonnes antimony in the second quarter of 2021.

Antimony supply chain risks

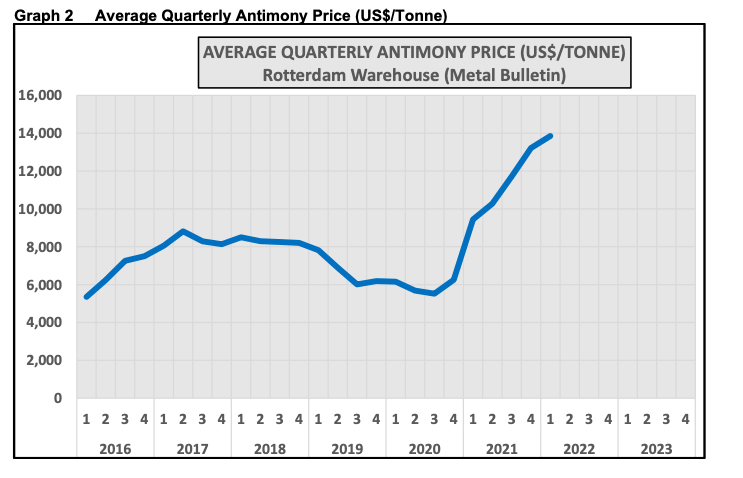

In 2013, China imposed restrictions for several years on the export of antimony-based products, which reduced availability and increased prices.

To maintain market control, China has continued buying antimony deposits from other countries to either obtain their supplies or shut down operations.

“Because of how important it is from a defence and high-tech point of view it is a bit ironic that we are relying on other countries for our military capability,” Hudson says.

While the US has no mined antimony sources, the Stibnite Mining District in Stibnite, Idaho is one of the largest known economic deposits of antimony outside of China and is currently under environmental review for mining redevelopment by Perpetua Resources.

“The Western world has no antimony supply security, even though we use it widely and broadly and can’t do without it,” Hudson says.

“The world is only starting to wake up to antimony and with Australia being the world’s fourth largest in terms of reserves, we will play a key role going forward.”

Which ASX companies have exposure to antimony?

SOUTHERN CROSS GOLD (ASX:SXG)

Historically, ore from SXG’s Sunday Creek Project in the Victorian Goldfields was treated onsite or shipped to the Costerfield mine, only 54km to the northwest of the project, for processing during WW1.

The company listed on the ASX back in May with a full suite of projects in tow including Sunday Creek, the Red Castle and Whroo joint ventures also in Victoria, and the Mt Isa Project in Queensland.

Hudson says the beauty about Sunday Creek is that it is a classic, Victorian opportunity no different to Costerfield or Fosterville (the largest gold mine in the state) in that it is a gold/antimony field which no one has investigated at depth.

So far, exploration has identified five high-grade shoots within a 1km core area, with another 10km of a mineralised trend defined by historic workings and soil sampling remaining to be tested in the modern era by drilling.

Investors have been switched on to the potential for high-grade epizonal gold/antimony at depth beneath historic goldfields in the state thanks to the success at the regionally close Fosterville and Costerfield operations.

The two mining operations rank amongst the world’s highest-grade operations and ironically enough, are owned by Canadian companies Agnico Eagle and Mandalay respectively.

RED RIVER RESOURCES (ASX:RVR)

Red River’s Hillgrove operation is in Armidale, New South Wales.

To date, Hillgrove has produced more than 730,000oz of gold (in bullion and concentrates) and more than 50,000 tonnes of antimony plus material amounts of by-product tungsten – another strategic, critical mineral used in metalworking, construction, electrodes, and filaments.

The company recently hit 4.5m at 29.5g/t gold and 0.3% antimony from 466m, including 0.45m at 257g/t gold from 467.75m in its first hole at Bakers Creek, demonstrating extensional gold mineralisation at the historic mine.

Historically, Bakers Creek was the most productive mine in the Hillgrove field and produced more than 300,000 oz gold.

Given the exceptional exploration results recently produced at Hillgrove current market volatility and inflationary cost environment, the company has decided to undertake a strategic review before recommencing mining at the site.

NAGAMBIE RESOURCES (ASX:NAG)

Nagambie listed in 2006 to explore around the former namesake mine in rural Victoria, which produced about 134,000oz of gold from open pits between 1989 and 1995.

Southern Cross Gold has a 10% stake in the company, which grants it a right of first refusal over a 3,300km2 tenement package.

Earlier this month Nagambie confirmed Costerfield-style antimony-gold mineralisation at its Nagambie Mine in Victoria with all four diamond holes hitting massive stibnite veining, including pieces of solid, near 100% stibnite.

NAG executive chairman Mike Trumbull said at the time the delineation of the C1 and C2 massive stibnite veins is “undoubtedly the most exciting development in the company’s history”.

“The structural explanation that we have developed for these N to NNW striking veins suggests that the total number of C veins at the Nagambie Mine could be a very large number.”

GREAT NORTHERN MINERALS (ASX:GNM)

It’s been all about the high-grade gold inside an under-explored goldfield in North Queensland, last operated in the mid 1990s, before Camel Creek happened.

A reverse circulation drilling program undertaken towards the end of 2021 uncovered high-grade antimony in addition to gold, leading the company to consider including the intersections in a mineral resource estimate for Camel Creek.

Camel Creek is one of three projects forming what is known as the Golden Ant project, about 200km from Townsville.

One highlight from the drilling includes drill-hole CCRC86, which intersected ‘bonanza grade mineralisation’ of up to 1m at 105.5g/t gold and 0.6% antimony from 127 – 128m down hole, representing a compelling target for potential underground mining operations.

As part of the Golden Ant Scoping Study, targeted for completion by the middle of the year, McLean says metallurgical test work will be carried out to better understand the potential to produce an antimony concentrate from the Camel Creek deposit.

A four-pronged, fully funded, high-impact work program is underway to increase the mineral resource base even further, deliver exploration success, advance the scoping study, and understand the full extent of the antimony potential.

Related Topics

SUBSCRIBE

Get the latest breaking news and stocks straight to your inbox.

It's free. Unsubscribe whenever you want.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.