Your guide to mining feasibility studies

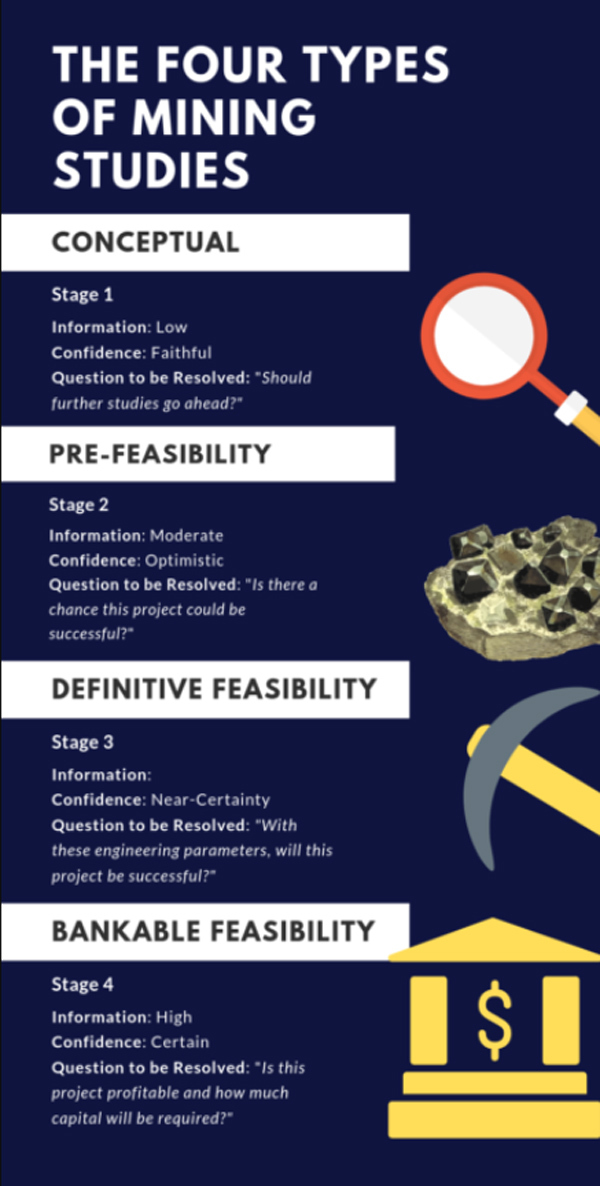

Here are the four types of mining studies. Pic: Getty Images

Mining isn’t just about finding rocks. It’s also about finding out whether mining those rocks is worth the time, energy, and money — that’s where feasibility studies come into play.

Getting resources out of the ground requires a lot of money, and investors won’t risk their capital on projects without a reasonable prospect of success. One way of determining this is through feasibility studies.

There are four stages, each with more certainty attached to them:

- Conceptual study

- Pre-feasibility study

- Definitive feasibility study

- Bankable feasibility study

THE CONCEPTUAL STUDY

The conceptual study (or scoping study) is the first of these and with limited information, many parameters are assumed or factored because drilling is not done.

Of course they have to be reasonable but they are less strict than later stages because all a scoping study determines is whether or not further studies should go ahead.

Resources may be Implied, Indicated or Measured.

Companies may have a mixture of resource confidence, and in those cases will indicate them in the study.

In scoping studies, headline figures will be particularly noted, such as projected annual production and net present value.

For example, when AVZ Minerals (ASX: AVZ) released an expanded scoping study for their Manono Lithium Project in May last year, they announced that the study predicted annual lithium concentrate production of 1.1 million tonnes and a net present value of around US$2.6 billion.

26.75 per cent of its projections were from Measured resources, 40.5 per cent Indicated and 32.75 per cent Inferred.

If a company’s scoping study figures are similarly compelling then the company and its engineers can proceed to the next stage.

THE PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY (PFS)

While this is still only a preliminary step, here metallurgical test work is done to develop processing parameters for development.

At this stage the miner wants to see how the material it’s dug up so far respond to processes such as floatation, gravity concentration or leaching.

This will give them cost and production estimates, an idea of any safety issues which may arise in processing, and any other project obstacles they may run into.

None of these parameters are as comprehensive as at later stages, they are sufficient to deduce the most appealing possible scenario to form the basis of the next stage, the definitive feasibility study.

THE DEFINITIVE FEASIBILITY STUDY (DFS)

The question ‘To mine or not to mine?’ is resolved at this stage.

By now all processing parameters have been through detailed and accurate metallurgical test-work has occurred.

While inevitably some will be assumed, these are usually realistic because they are dependant on all mining, processing and other considerations taken at and before this point.

As an example, Arafura Resources’ (ASX: ARU) Definitive Feasibility Study for its Nolans project in the Northern Territory forecast average annual production figures of 4,356 tonnes of Neodymium-Praseodymium oxide and and 135,808 tonnes of merchant grade phosphoric acid.

The mine’s life will be 23 years and average annual pre-tax earnings at A$377 million EBITDA, although the project would require just over $1 billion in capital and up to 650 employees at the peak construction phase.

The company used the study’s release to proclaim to investors, “the Project is financially and technically robust to support a long life operation”.

THE BANKABLE FEASIBILITY STUDY

Often you will hear the term ‘bankable feasibility study’ — and it’s more about financing than geology.

The bankable study doesn’t usually differ in project parameters from the DFS, but they include a stack of detail on what terms financiers should lend to them to make the project sing.

Despite the name, the financier won’t necessarily be a bank. It could be a joint venture partner or equity investors.

So, as easy as it is to be impatient with the company you invested in raising money only to spend them on studies, these are all an important part of the process.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.