ASX gold stocks guide: Here’s everything you need to know

Amazing gold Pic:Getty

In times when gold prices are notching up steady gains it is easy to forget how once out of favour the yellow metal was.

For all of the 1990s and into the early 2000s gold traded at under $US500 ($697) an ounce.

Britain sold 400 tonnes of its 715-tonne holding between the years 1999 and 2002, at a price of $US275/oz. Analysts say this price marked a rock-bottom low for the gold market.

Britain was not alone. Other countries’ central banks also sold some of their gold holdings in the 1990s, including Argentina, Belgium, Canada, and the Netherlands.

Australia sold off some of its gold in 1997, 167 tonnes at a prevailing price of $US400/oz.

In 2020, Australia’s gold holdings amount to only 80 tonnes, nearly all of it is stored at the Bank of England’s vaults in London, according to the Reserve Bank of Australia’s website.

Gold falls out of fashion at Millennium

There was a broad feeling among economists in the lead up to the Millennium and shortly thereafter that gold had a diminished role to play in central banking.

Bookended by two Iraq wars in 1991 and 2003, it was after all a time of relative peace, stability and prosperity as economies expanded under globalisation and low inflation.

The United States held sway as the world’s largest economy and only superpower after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the US dollar currency was king.

Western Europe was forging an ever-closer economic union and had launched its own currency, the Euro.

Asian economies were slowly recovering from a devastating 1990s economic crisis.

China was quietly building its economy, having taken back Hong Kong from Britain, and Macau from Portugal.

Then, around 2007-2009, something drastically changed in the global economy and for gold.

Global Financial Crisis, or the great unravelling

The world’s financial centres were hit by a global financial crisis that caused debt markets to freeze, banks to crumble, and left investors and depositors adrift.

Gold with its lack of counterparty risk and safe-haven-in-a-storm status was seen as a trustworthy alternative to financial instruments and paper contracts.

The gold market started to build up a head of steam. Slowly its price began to ascend and went on to peak in 2011 at $US1,800/oz.

It did recoil in the years thereafter, but gold’s price has managed to stay above $US1,000/oz, and it went on to trade over $US2,000/oz in mid-2020.

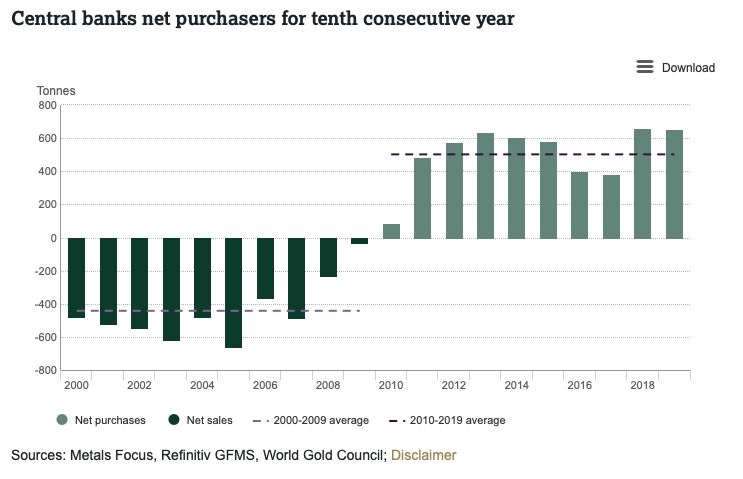

Not only did investors sense a change in the economic weather, central banks did too.

Gradually, central banks started to accumulate the yellow metal in their vaults again.

Central banks swing back to net gold buyers

In 2019 they bought a total of 650 tonnes of gold – the second highest annual total for 50 years, according to the World Gold Council.

“This marks 10 consecutive years of net purchases, with global official reserves now 5,000 tonnes higher than end-2009 at around 33,920 tonnes,” the World Gold Council said.

China and Russia have led the charge of central bank buying of gold. China added 95.8 tonnes to its gold reserves last year and Russia’s central bank bought 158 tonnes in 2019.

Their holdings have reached 2,299 and 1,948 tonnes, respectively. China and Russia are still a long way behind the US with 8,133 tonnes, according to World Gold Council figures.

More is yet to come, as a World Gold Council survey of central banks in 2020 revealed 20 per cent wanted to add to their holdings, up from 8 per cent a year ago.

Gold price performance, lack of default risk and store of value attributes

Central banks in the survey gave several different reasons for their gold accumulation.

Top cited reasons were negative interest rates, gold’s strong price performance in times of crisis, gold’s lack of default risk, and its function as a long-term store of value.

There are of course other uses for gold in jewellery, industry, dentistry and as an electrical conductor, and even as anti-glare protection in astronauts’ space helmets.

But it is gold’s role as an investment product that gains the most attention, with sales of gold bullion and bars, and an interest in exchange traded funds rising dramatically in 2020.

“The global response to the [COVID-19] pandemic by central banks and governments, in the form of rate cuts and massive liquidity injections, fuelled record flows of 734 tonnes into gold-backed ETFs,” the World Gold Council said in a July 2020 update.

Can it be investors are deciding to own gold for exactly the same reasons as central banks?

Demand driving ASX gold stocks

The higher gold price is one of the key drivers propelling investors towards ASX small cap gold stocks.

The higher the price of gold, the more likely an explorer will generate a return on their investment if they find gold – simples.

So, it’s no surprise the recent surge in the Aussie dollar gold price has again ignited investor interest, especially as production is declining.

Australia, for example, is set to see a major drop-off in gold production as early as 2020, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

“In the case of Australia, despite production being on track to hit a 26-year high of 10.2 million ounces in 2019, we estimate that Australian gold production will start to decline thereafter,” Chris Galbraith, an analyst at S&P, said.

“We are forecasting a 9 per cent fall year-over-year in 2020, and we expect the country’s production to reach a generational low of 6.8 million ounces by 2022 – a 33 per cent drop within only three years.”

S&P attributes the anticipated decline to the short mine lives of recent start-ups and some significant mines approaching the end of their life.

Since the end of the mining boom, many Aussie gold explorers and producers have become better at managing their costs and setting themselves up to be low-cost producers.

Investing in ASX gold stocks

There are more than 400 ASX stocks with exposure to gold projects in Australia and around the world. This number is growing at a rapid rate as companies shift their focus to gold assets from (currently) less-desirable commodities, like battery metals.

And there’s a theme emerging as ASX-listed explorers look to revitalise very old, often high-grade mines in this buoyant gold price environment.

Old mines usually come with an existing resource — even if it isn’t up to JORC 2012 standards — and fresh gold is easier to chase down, which means a quicker path to production.

WA gold explorers revive historic mines, make new discoveries

Kingwest (ASX:KWR) plans to unlock value at the historic Menzies and Goongarrie goldfields north of Kalgoorlie in WA and, Norwest Minerals (ASX:NWM) with its Bulgera project near the Plutonic gold operation in WA.

Rox Resources (ASX:RXL) and its joint venture partner Venus Metals (ASX:VMC) are advancing their Youanmi project 480km northeast of Perth in WA that churned out historic production of 667,000oz up to 1997.

When it comes to big, greenfields (new discoveries) projects, De Grey Mining (ASX:DEG) already has a 2.22-million-ounce resource at 1.8 grams per tonne (g/t) for its Mallina project in the Pilbara, which hosts the company making Hemi discovery.

The company’s Pilbara gold project hosts over 200km of mineralised shear zones spanning a 1,480sqkm landholding.

De Grey is rapidly advancing exploration in its drive to upgrade and expand the known resources, as well as discover new deposits.

Also in WA, Breaker Resources (ASX:BRB) is advancing its 1.1-million-ounce Bambora deposit, part of the Lake Roe project, 100km east of Kalgoorlie in Western Australia.

Drilling has confirmed the resource is part of a 9km-long gold system, which the company said was comparable to Kalgoorlie’s Golden Mile, after which Bombora hosts the second widest and most fractionated dolerite in WA.

Great Southern Mining (ASX:GSN) has focused on expanding tenure along strike from known prospective trends hosting gold deposits at its Cox’s Find mine 65km north of Laverton in WA, which produced 77,000 ounces at more than 21g/t between 1935 and 1942.

“One only has to look at the depths of extraction of modern-day mining (and subsequent resource cut-off grades) to know that this wouldn’t be the first historic gold mine to be resurrected on significant ounces discovered at depth,” Great Southern chairman John Terpu told Stockhead.

He is talking about guys like WA-focused Bellevue Gold (ASX:BGL), which is enjoying wild success, and has raised $35m from an oversubscribed share placement for its 100 per cent-owned Bellevue project in WA’s Yilgarn craton.

Also in WA is Ora Gold (ASX:OAU), which is nearing gold production from its Crown Prince project near Meekatharra. The company has set a production target of 177,500 tonnes at 4.1g/t from a 75m deep open pit.

Ora Gold’s strategy is to pursue near-term gold production opportunities while exploring for large gold and base metal deposits.

Queensland and Tasmanian gold explorers

Moho Resources (ASX:MOH) has made a promising gold discovery in north Queensland at a project called Empress Springs, part of a joint venture with resources giant IGO Ltd (ASX:IGO).

The company says there has been no previous drilling for gold and base metals in the Empress Springs area, yet it is right near the historic Croydon goldfield that produced 1.2 million ounces of gold.

Following a review of the maiden drilling results, Moho applied for an additional 2000sqkm around the North Queensland project.

The systematic exploration of old gold workings continues to pay off for explorer Ausmex (ASX:AMG), which has two world class projects in Mt Freda at Cloncurry, Queensland, and in Burra in South Australia.

Great Northern Minerals (ASX:GNM) is drilling at its Northern Queensland projects that ceased operations in the 1990s after production of 150,000oz at an average grade of 1.9g/t.

Silver Mines (ASX:SVL) is dusting off the Tuena project in NSW, and kicking off a 4,000m drilling program at the series of historic hard-rock and alluvial gold mines worked between the 1850s and early 1900s.

Stavely Minerals (ASX:SVY) — even though investor attention is focused on that huge copper discovery in Victoria — has the Mathinna project in Tasmania, essentially untouched since 1932 up to when it had produced 289,000oz of gold.

Victorian gold’s renaissance

In Victoria, Kirkland Lake Gold’s (ASX:KLA) recent success at the Fosterville gold mine, has seen it emerge as one of the lowest-cost and most profitable gold mines in the world.

This has brought Victorian gold back into vogue – attracting a host of explorers eager to repeat its success by finding new multi-million-ounce deposits.

Chalice Gold Mines (ASX:CHN) is one of the three ASX-listed players that have the most prospective parts of the Bendigo goldfield in Victoria stitched up.

The company’s Pyramid Hill gold project has a 4km gold trend at its Kari prospect, and covers 5,000sqkm in the northern area of the Bendigo gold zone.

The Victorian government estimates there is 32 million ounces of undiscovered gold in the Bendigo Zone beneath Murray Basin cover, where Chalice now has a ground position.

Bendigo produced more than half the world’s gold for 40 years between 1850 and 1890. But up until two or three years ago, it had taken a backseat in the hunt for gold in Australia.

And still more ASX gold stocks…

Cervantes (ASX:CVS) is an interesting one, having flipped from aquaculture to gold exploration in 2016.

The company is exploring the Primrose project in WA’s Paynes Find goldfield, an area containing 37 historic mines that produced 80,000oz at an average grade of 28.6g/t.

Sultan Resources’ (ASX:SLZ) Lake Grace project, 250km south of Perth, is in the same neighbourhood as Ramelius Resources’ (ASX:RMS) recently acquired 700,000oz Tampia deposit and Ausgold’s (ASX:AUC) 1.2-million-ounce Katanning deposit.

It is also surrounded by tenements held by a joint venture between Cygnus Gold (ASX:CY5) and larger miner and explorer Gold Road Resources (ASX:GOR).

Sultan also owns the Ringaroo gold-copper project in NSW’s Lachlan Fold Belt, home of Alkane Resources’ (ASX:ALK) Boda discovery.

African gold discoveries

The most talked about African gold discovery in 2020 was Predictive Discovery’s (ASX:PDI) valuable find at the Kaninko project in Guinea.

An initial drilling program at North-East Bankan by Predictive returned numerous shallow, thick, and high-grade gold intercepts like 10m at 26.52g/t gold. The news sent shares up 733 per cent in April 2020 when it was announced, making it the biggest one-day gain since 2017.

Okapi Resources (ASX:OKR) is exploring for gold in Western Australia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The company also has an 8.4 per cent stake in Amani Gold (ASX:ANL), which owns the Giro gold project that is also located in the DRC.

Okapi is also assessing other potential project opportunities both within and outside of the DRC.

West African explorer Tietto Minerals (ASX:TIE) has just increased its Abujar gold project resource from 1.7 million ounces to 2.2 million ounces – and there’s more to come.

“We will be very busy in 2020 as our fleet of four company drill rigs are on track to deliver 50,000m or more of drilling by Q3 2020, doubling all drilling at Abujar to date, as we target continuing rapid growth in our gold resource inventory,” said managing director Caigen Wang.

West African Resources (ASX:WAF) has found itself a nice spot in West Africa, which has been yielding quite a bit of high-grade gold for the junior.

The company previously struck grades of up to 860g/t in Burkina Faso and expects its Sanbrado gold mine in the country to be a highly profitable operation producing as much as 301,000oz in the first year.

All-in sustaining costs (AISC) of under $US600/oz for the project’s

first five years would see the company make a sizeable profit in an environment of high gold prices.

At Stockhead, we tell it like it is. While Great Southern Mining, Great Northern Minerals, De Grey Mining, Moho Resources, Ora Gold and Sultan Resources are Stockhead advertisers, they did not sponsor this article.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.