World War Hack: Open-source espionage, global cyber-militia descend on Russia

News

Russia’s fight with Ukraine has shown how cyber-attacks are the first weapon drawn during a modern geo-political conflict and truth is the first prize of war.

Yet, Russian President Vladimir Putin – for now anyway – is yet to deliver a devastating cyber-blow and has so far been unable or unwilling to unleash large-scale cyberattacks.

For now at least there appears enough respite for individuals, corporates, tech-firms, a coalition of willing US allies and a gaggle of NATO-aligned intelligence services to push back against the Kremlin’s digital objectives and its disinformation hobbies.

Certainly there appears an enthusiasm from within the global halls of digital power to take Putin on in the digital domain… and even beyond.

I hereby challenge

Владимир Путин

to single combatStakes are Україна

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 14, 2022

In response to Russian cyber attacks which preempted and then tore a few holes through Ukrainian infrastructure as Mr Putin launched his ‘Special Military Operation, ‘the Ukrainian government had already begun recruiting the world’s first multi-national volunteer digital army.

In fact months before U-Day, the US had already sent in its digital special forces equivalent – a few professional soldiers of the US Army’s Cyber Command, while others were civilian contractors or staff at NASDAQ-listed companies which help defend critical infrastructure assets from exactly what Mr Putin’s homegrown hacking teams agencies were working upon Ukraine fever since the successful 2015 attack which left parts of Kyiv without electricity.

Experts warn that Russia may yet unleash a devastating online attack on Ukrainian infrastructure of the sort that has long been expected by western officials.

But for now the years of labour and about ten weeks of hardcore, targeted bolstering, may explain why Ukraine’s online world is still operating.

But these multi-national hacking squads – Bond University’s Professor Dan Jerker Svantesson says a more accurate term would be “cyber-militia,” – have loose affiliations which are only getting looser. He says, given what will be a global volunteer force made up largely of civilian sympathisers hanging out in basements, and cafes – it’s more militia than special force.

In any case, it not only aims to stave off Russian hack-attacks, but will draw up counterstrikes of its own.

Svantesson says there could be more than 275,000 volunteers from around the world already answering the call, “although verifying an exact figure is impossible at the moment.”

Karly Winkler, deputy director and senior analyst at the International Cyber Policy Centre (ICPC) reckons a so-called cyber-militia is a hell of a risky proposition – “lacking coordination, controls and clear boundaries.”

“Making it legal for civilians to hack each other in a cyber war is a minor aspect – hacking into adversaries’ systems to steal information is one thing, disrupting them is something entirely different because it causes damage and have unintended consequences.”

The bigger issue here Winkler says, is accountability and minimising the risks of collateral damage.

“Nation states answer to the UN Human Rights Commission and international law for warfare, which means that their activities are focused, measured and include careful risk strategies for follow-on effects – for both combatants and bystanders,” Winkler says.

“Hacktivists and criminal groups are *not bound by any of the same rules, which means that they can cause indiscriminate chaos that impacts innocent people, and can obstruct valuable services such as allied cyber operations, battlefield recovery (like the Red Cross) and Russian resistance efforts opposing the current regime.

“If this Ukrainian cyber-militia accidentally releases another NotPetya, or causes harm to vulnerable people from their actions, who is responsible for that? Who makes reparations afterwards?”

In June 2017, when the NotPetya malware first started taking away the sense of smell of computers around the globe, it didn’t take long for authorities in Ukraine, where the infections began, to wave a big pointy finger at Russia for the minor cyber-pandemic which cost circa $13bn.

NotPetya was just another stray digital bullet in the but-adolescent tiff between neighbours, but this one, fired via a popular piece of Ukrainian accounting software, got out and into the wider world and did a fairly outstanding job of ruining stuff.

Senetas ASX:SEN CEO Andrew Wilson agrees, saying these kind of groups – from ‘aggressor states and state-sponsored cyber-gangs’ – can target everything from government services, defence force military and weapons systems, defence suppliers, communications networks, energy and other critical infrastructure and commercial IT systems – all in an effort to cripple the targeted state.

“And the victim states’ allies have also been targeted – to do harm and capture defence intelligence,” Wilson adds. “So, such wide-scale cyber-attacks also involve significant collateral damage – numerous governments and enterprises in other regions.

“The targeted state is far from the only victim to suffer catastrophic damage.”

The Anonymous collective is officially in cyber war against the Russian government. #Anonymous #Ukraine

— Anonymous (@YourAnonOne) February 24, 2022

The geo-political conflict and cyber-landscape have also become a battlefield for third parties who cannot get directly involved to make their influence felt, such as what the hacker group Anonymous has done in its attempts to disrupt Russian state websites and communications channels.

Andrew Wilson at Senetas says information has enormous value to aggressor states – and why quality encryption plays an essential kind of, ‘last line of defence,’ role against a determined state – like one which has gotten itself into an asymmetric conflict entirely of its own invention.

In 2018, the much-feared CyberCaliphate, a supposed branch of Islamic State, was revealed by an excellent Associated Press investigation to be aligned with the same St Petersburg troll farm which bought us such hits as intervening in the American election, hacking and dumping Democratic Party files and exposing the emails of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign chairman, John Podesta. The Russians had been playing false flag all along in a long-term, low cost seemingly random and parallels the online disinformation campaign by Russian trolls in the months leading up to the election in 2016.

Winkler says assigning blame is hard.

Because the battlefield is opaque and the enemy ingenious and unscrupulous.

“This tweet from a colleague of mine shows a number of the sophisticated cyber teams – APTs or Advanced Persistent Threats worldwide, (but by no means complete!).”

An interactive map of global #APT s attributed to country or region. Source: https://t.co/5zT35gzwuq #mgmtporn pic.twitter.com/if9aP1iVYd

— technoid (@techstrat_99) February 24, 2022

It’s definitely not always the same ones, each has areas of expertise and the destructive focused teams (eg. Sandworm) are usually distinct from the disinformation ones involved in electoral interference.

Bond Uni’s Dan Jerker Svantesson says given future wars are also likely to be fought in cyber space, “sooner or later, Australia will have to reckon with the prospect of significant numbers of citizens becoming involved in foreign cyber warfare. And there’s truly no time like the present.”

And according to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), the invasion of Ukraine marked another historic moment in human conflict – “when Western powers started giving away the intelligence jewels.”

“In the four months before the war, the US shredded top-secret taboos to reveal detailed information about Russia’s build-up to war. The extraordinary series of disclosures happened almost as quickly as secrets were collected and assessed.

US intelligence used a “rebuilt source network in Russia, government and commercial satellites tracking the movement of Russian troops, an improved ability to intercept communications, and even open-source material culled from Russian social media.”

And then… the White House, decided not to lock the detail in the state secrets vault, or pass it on to Harrison Ford or the CIA.

Instead, they gave it to everyone. And in this way, the era of the open-source counter-intelligence war began.

Ex-Security Enterprise Architecture leader at the Department of Defence, now the CEO at archTIS ASX:AR9 , Daniel Lai says Ukraine is already a textbook example of how important it is in modern warfare to be able to help share intelligence and resources with allies.

“Securing multinational coalition communication and information sharing is absolutely critical, as you can be certain when it is a conflict between developed nations that attempts will be made to acquire valuable information. While we tend to imagine cyber-warfare involves hacking into military equipment and disrupting communications, in reality most of the work is focused around access to information.

“Knowing what your opponent knows is an incredible advantage that has real implications on the front lines.”

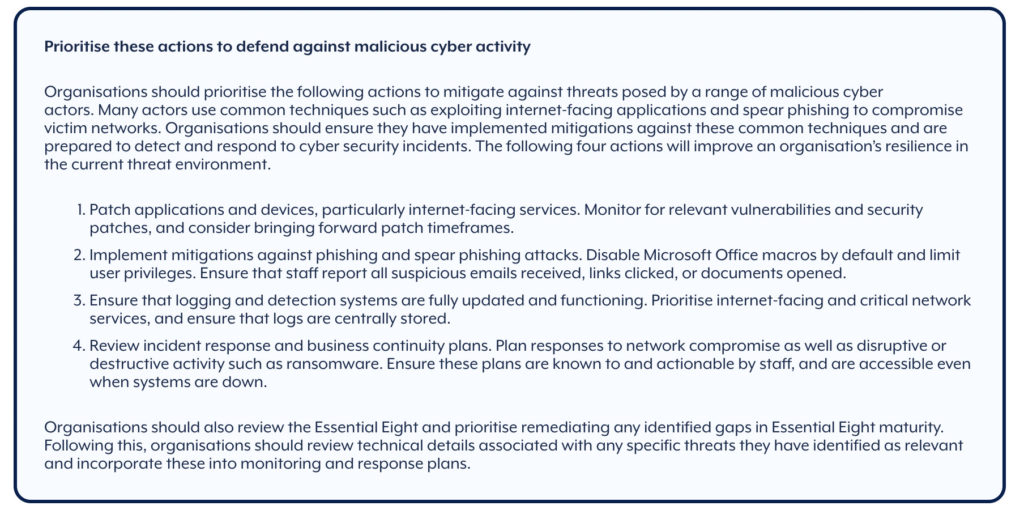

The situation in Ukraine is already having an impact in Australia that the public can see.

The Australian Cyber Security Centre’s advisory last week to ‘urgently adopt an enhanced cybersecurity posture’ is a warning for all businesses that they might become collateral damage in a cyber attack aimed elsewhere. The problem is, that if businesses are only reacting now to the threat, the chances are it’s too little, too late.

They need to be looking at implementing secure services like the ones used in Defence, and the Government needs to be guiding them in that direction.”

Wilson at Senetas was encouraged that cybersecurity experts and key intelligence agencies consistently warned enterprises, defence forces, governments and critical infrastructure operators of increasingly persistent and threatening cyber-attacks by Russian based cyber-crime gangs.

“These ranged from ransomware, other malware, network infiltration and hacking attacks to data theft, eavesdropping and brute force and denial of service attacks.”

Senetas says information has enormous value to aggressor states – where strong encryption plays the essential role of ‘last line of defence’.

“It ensures that when an attacker gains access, the encrypted data is useless in their hands. Significantly, authenticated encryption adds a second layer of protection for data networks by preventing the ingress of malicious content and malware.”

Because Russia has threatened to retaliate against Western nations for the economic sanctions imposed, governments and enterprises have been warned to expect ransomware and zero-day attacks on a level not seen before.

And despite China rejecting Monday reports that it would help resupply Russian weapons and munitions, the likelihood of China’s impressive cyber war machine getting in some match practice in the Ukrainian theatre are extremely high.

“Advanced state-of-the-art cybersecurity solutions are more important then ever,” Andrews says.

“Recent history’s catastrophic ransomware attacks have made that clear.

“Effective protection against ransomware, malware, unknown and zero-day attacks requires ‘signature-less’ Content Disarm and Reconstruction technology where all data is assumed to be malicious.”

Defending against cyber-warfare requires enormous investment into securing almost every area of a nation’s operations, from banks and government departments through to logistics providers and farmers.

Earlier this month, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Marisa Payne urged governments, the private sector and households “to remain vigilant about the ongoing threats we face in cyberspace.”

The Federal Government has already pledged some $1.7bn over 10 years to build new cybersecurity and law enforcement capabilities while also legislating to protect national critical infrastructure from malicious cyber attacks.

Andrews and the broader public and private sector all expect greater investment here at home and the Australian Cyber Security Centre’s (ACSC) guidance – distributed last week – openly encouraged Australian businesses to get serious about their cybersecurity practices.

“Additionally, as a global cybersecurity supplier, and the breadth and impact of Russian cyber-attacks are reaching beyond Ukraine alone, we expect similar increases in international cybersecurity investment – in government and enterprise sectors.

Many nations will be watching how this war plays out and examining how they, and their critical institutions, would defend against the tactics being used.

Both Andrews and Lai believe they’ll be looking to boost resilience through both prevention of malware attacks and data protection against hostile breaches.

“The reported attack on Toyota both a few weeks back and this weekend, is a good example of what cyber-warfare looks like. Whilst Toyota itself wasn’t breached, its suppliers were. That weak link meant Toyota’s operations were shut down all the same,” Andrews warns.

Cyber-warfare from now will look similar – shutting down factory production, disruptions to power delivery and IT systems – it’s Die Hard 3.0 and Bruce Willis is getting too old for that sh#t.

As with all security systems, cybersecurity cannot provide a 100% certain guarantee – nothing is truly impenetrable. As cyber-criminals discover stronger defences they develop new approaches.

“Whilst formidable cyber-defences exist, they encourage less direct tactical routes to achieve the aggressor’s goal, such as phishing a member of staff to inadvertently click a link or attachment that provides access to an attack. Or, as in Toyota’s case, targeting the resources an institution needs to function in order to disrupt.

“Suppliers of cybersecurity solutions like ourselves are in a never-ending arms race with attackers, and play a vital role in keeping economies safe.”

Karly Winkler over at the ICPC says the ‘arms race’ is a tough one because, a truly committed, sophisticated actor will usually find a way in – defence is harder than offence.”

“However, the effort that a state actor will go to usually depends on how well resourced it is, how many adversaries it needs to keep track of, how much it cares about each one and whether they care about being caught.

“Russia can’t retaliate against the entire world with high-level attacks, and we have seen less than we’d have expected against their top priorities (Ukraine & the US) right now.

And let’s not forget, as of writing, Ukraine’s critical infrastructure has been blown to hell, but assets like its electricity grid other infrastructure are

Its president is an online sensation and a digital folk hero, streaming live defiance.

“However, they do have a suspected history of collusion with their very efficient, effective and wealthy criminal underworld who will pick off easy targets at scale.”

Opportunists follow the easy money, which can range from attacks using open source or Darkweb products, to stealing credentials, to the ‘spray-and-pray’ approach – high-volume, low-effort attacks that shouldn’t succeed against a conscientious target, but still land often enough to be profitable.

“If we can raise the bar high enough across the board to become not worth the effort, we’ll be fine,” she says, a little unnervingly.

“But good security practices take effort and consideration…”

At Stockhead we tell it like it is. While Senetas and archTis are Stockhead advertisers, they did not sponsor this article.