Honey, I shrunk the kids …and the GDP: China’s population dive amplifies Beijing’s delusions in Davos

Via Getty

In Switzerland this week hobnobbing with the world’s greatest moneybags, China’s No. 2 by a very long way, Head of the State Council, Premier Li Qiang arrived in Davos apparently prepared to the nth degree and set about delivering his missive.

Gathered in the snowy resplendence in Davos at the World Economic Forum, China’s second most important man said the world’s second-most important economy was just fine, really.

And remember, we are open for business.

What kind of business can new China offer?

On Wednesday, data showed that China’s economy grew 5.2% year-on-year in the fourth quarter, missing forecasts for a 5.3% expansion, but it’s the official absence of concern which might be giving traders extra angst.

Li is the No. 2 ranking top dog in the Chinese government after Forever President Xi Jinping, and the most senior Chinese politician to visit Davos since Xi in 2017.

Surrounded by a Chinese delegation of 140 people to this week’s five-day meeting of global political and business leaders, China brought as many as 10 ministerial-level officials related to China’s economic affairs, according to the news website Politico.

The attempt to talk its way back into the economic good books follows years of tit-for-tat trade wars with the US and its lackeys (like us) while Europe and the States have imposed tougher and tougher restrictions on investment in China – especially across the most sensitive and most essential sectors, like artificial intelligence – and both the US and the EU have banned the export to China of high-end computer chips, fearing they could be used by its military.

Against this backdrop Premier Li delivered what his guys would’ve called a combative yet welcoming speech, when in fact the closely studied address was as delusional as it was unexpected.

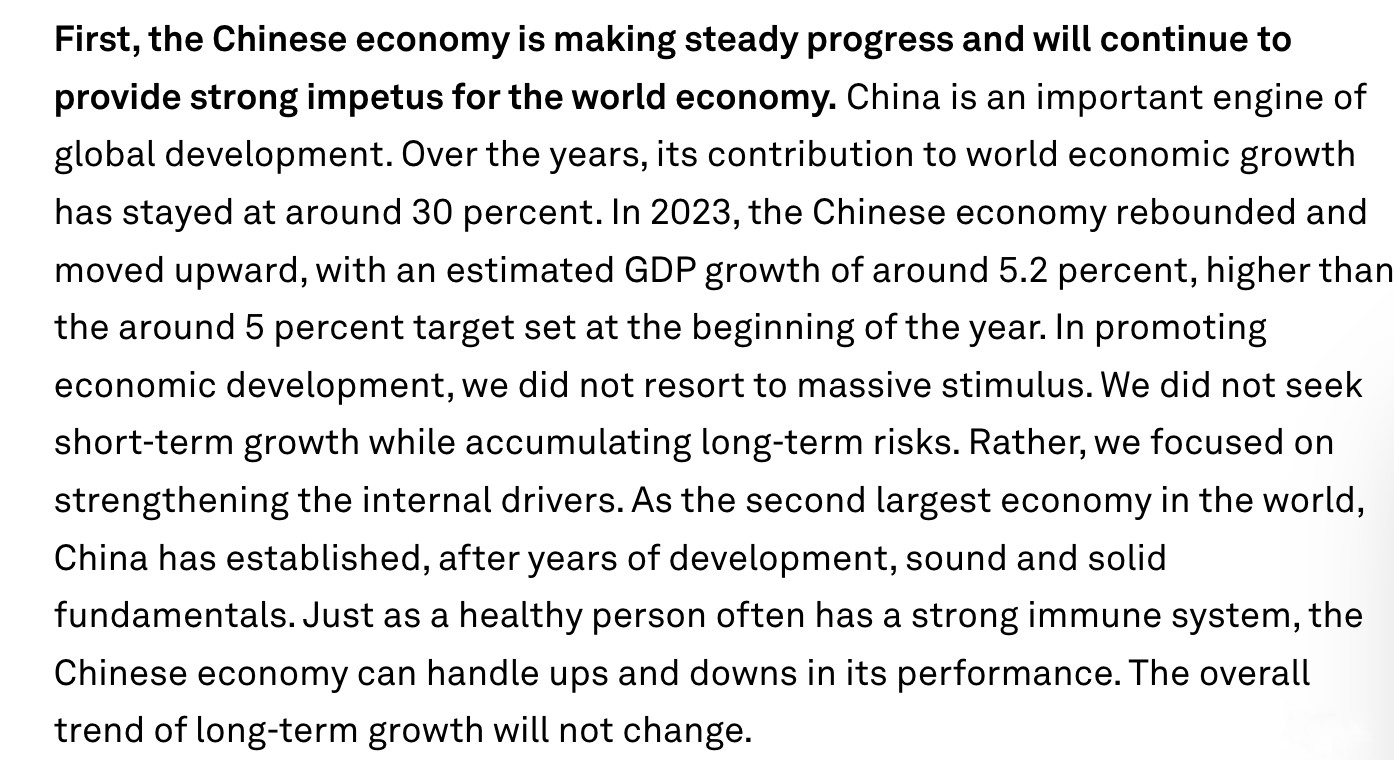

Li drip fed a GDP sneak peek, saying that China’s economy was estimated to have grown by 5.2% last year – a handsome beat on the official target of 5% – and reflective of some really genius leadership.

China managed to pull its economy up 5.2% last year, beating the official target and the 3% uptick from the year before.

But just how strong are those ‘internal drivers’?

China’s economy was 5% bigger than in 2022, sure, but that’s actually a fairly small increase from a year plagued by Covid lockdowns. In fact, it’s estimated that the country would have fared some 2% worse if 2022 had been a more regular year.

This especially true he mused, because China beat the target without resorting to its usual game plan of throwing money via infrastructure stimulus at the problem.

He didn’t mention that 4th GDP was a miss.

He didn’t mention that the comparative year (2022) provided an incredibly low bar for the achievement.

And he skipped the bit about 5.2% being among some of the slowest Chinese GDP growth in decades.

Instead, he hailed China’s extraordinary economy, explained away various minor health issues within it and then sat back waiting for confidence of foreign investors to materialise out of the home team applause.

The Premier went so far as to break with unbreakable tradition and offer a preliminary glimpse of national gross domestic product for 2023, which had been scheduled for official release on Wednesday.

China’s economy last year grew at one of its slowest rates in more than three decades, official figures showed Wednesday, as it was battered by a crippling property crisis, sluggish consumption and global turmoil.

On China’s side for once is the last man to call Chinese officials “rat f..kers” in front of world leaders – that’ll be our Former PM Kevin Rudd.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos overnight, Rudd assured those listening that China’s economy is not headed for permanently slower growth.

Rudd believes that China’s economy is not peaking, nor is it permanently slowing down.

“The key question for the future is the restoration of Chinese domestic consumer confidence, because that is China’s best long-term guarantee and it lies at the heart of Chinese economic policy,” Rudd said.

It will take more than that to win over investors.

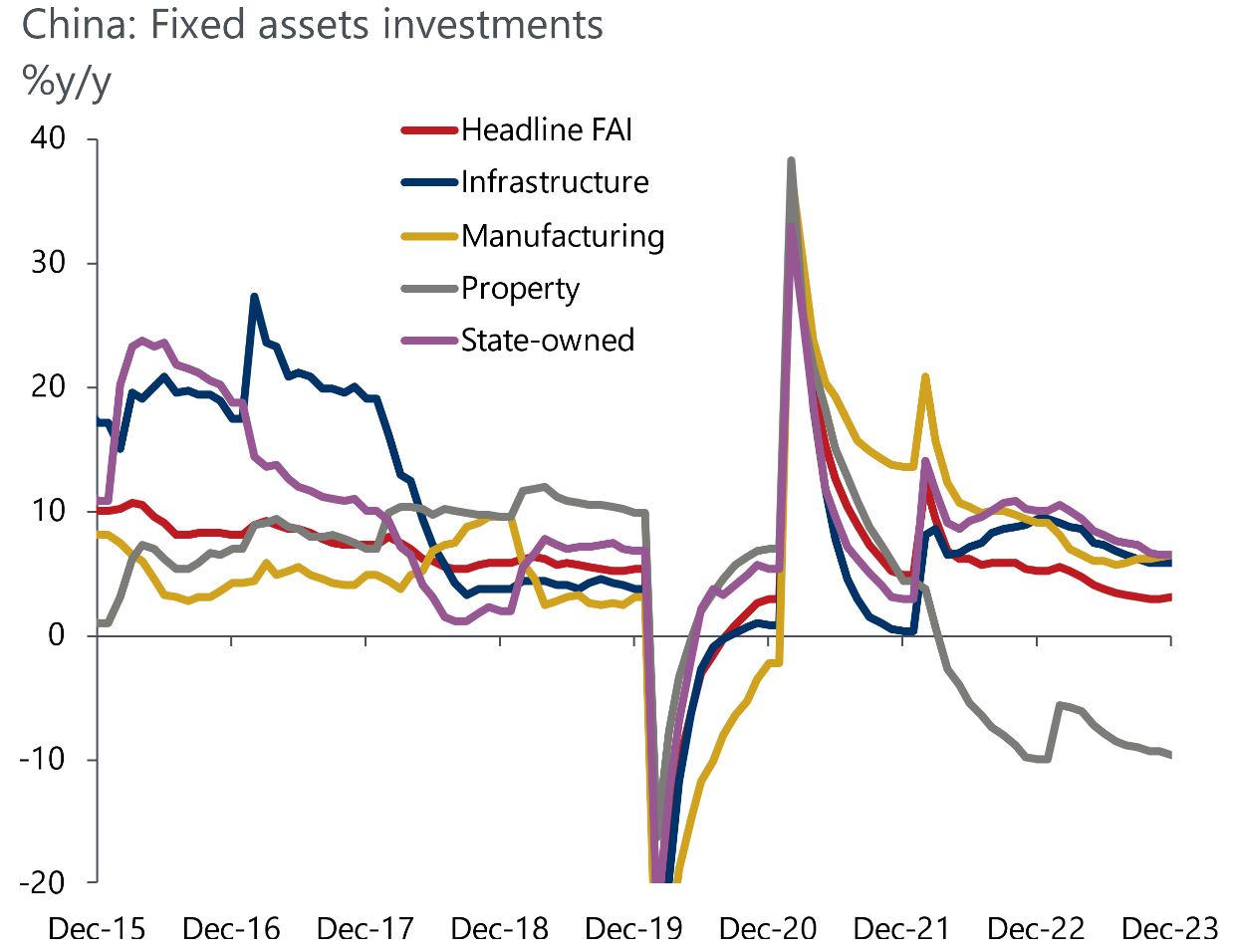

Especially when it looks like crackdown time, Xi Jinping-style. Again:

There are still a few major banks lurking around Beijing in the hope things aright themselves. But China recorded its first quarterly foreign direct investment deficit of $11.8 billion, the first time that has happened since records began in 1998.

In Beijing, Japan has one of the most active Chambers of Commerce in China. Like Australia – even more so – Japanese businesses rely on Chinese trade and services.

Last week the Chamber revealed from a recent poll that no less than half of all of Japanese companies in China did not invest in China or slashed their investment in 2023 compared with a year earlier.

And the rotting commercial core of China domestic economy remains its property sector, with the lame industry defying all the spoon-fed home remedies that the government’s calls supportive efforts.

The simple result is – the formerly indestructible spending power of the Chinese middle class is deteriorating as fast as their biggest assets lose value.

Li failed to mention as well that China is enduring its longest streak of deflation since 1999.

The Commonwealth Bank’s China economist Carol Kong said this week that China’s asset prices are in trouble.

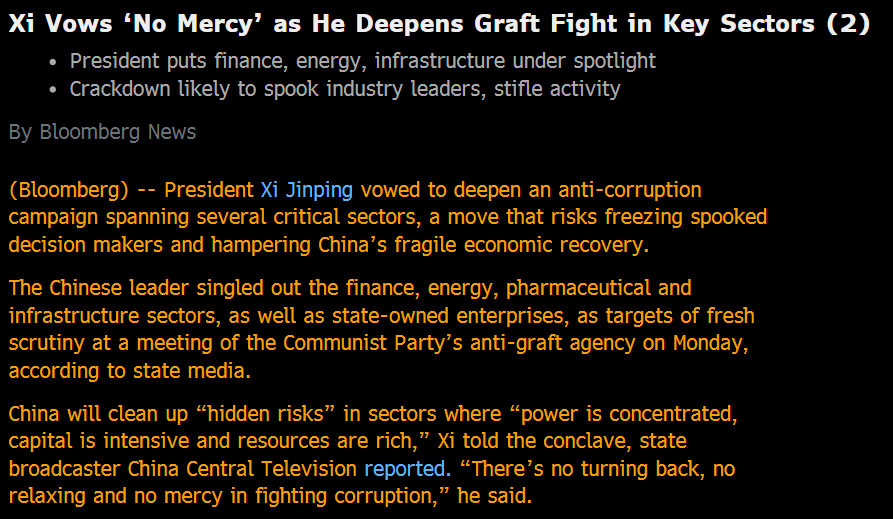

“For example, China’s benchmark CSI 300 index declined by more than 15% in 2023. In contrast, the Japanese and US equity markets posted very strong gains.”

To top it off, China has racked up debt worth 280% of its economy, an all-time high.

At the time of writing, it’s Thursday in Shanghai, where the Composite has already lost about 1.3% and the Shenzhen Component 1%.

These losses are starting to accumulate.

Both the mainland benchmarks at lunchtime on Thursday clocked their lowest ebb in about five years.

The comatose Chinese economic recovery has drifted with tectonic inevitability all the way back to pre-COVID levels.

To inject some life and confidence back into domestic demand, Kong said this week that there must be some genuine PBoC easing on the cards over the coming months. But as we’ve been reminded these last years, there’s only so much a central bank can do in times of economic doubt.

“One could argue monetary policy may only have a limited impact on boosting demand,” Kong warned.

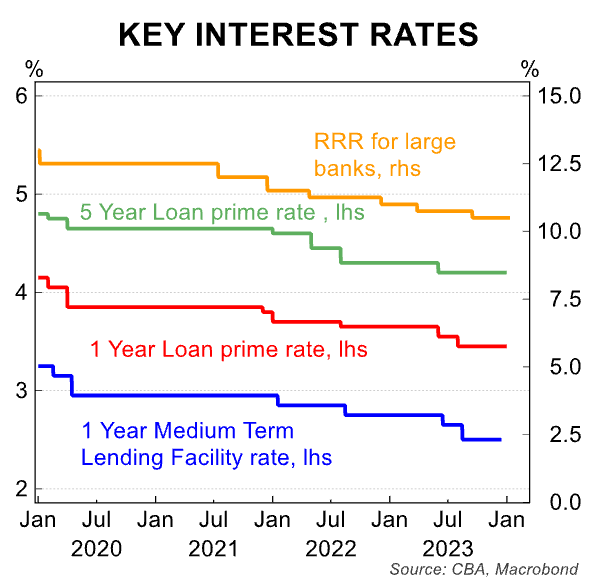

“Indeed, economic momentum remains weak despite the PBoC cutting the one year MLF rate and the RRR two times in 2023.”

Despite the upbeat talk out of Davos, China’s economic outlook and the total absence of aggressive policy support measures out of Beijing remains one of about 20 problems weighing heavily on investor sentiment.

It’s now 12 months after the loopy Beijing zero-COVID lock-ins… the digital surveillance, forced relocation to makeshift COVID-wards and uncompromising border controls. Unsurprisingly, overseas tourists and residents aren’t being tempted with China’s idea of newly relaxed visa rules.

Last night, the South China Morning Post reported that foreign visitor numbers are yet to return to China’s pre-pandemic levels.

According to official data from China’s National Immigration Administration (NIA), the number of foreign nationals residing in China “has rebounded to 85% of the level at the end of 2019”.

This is not a victory, even if the numbers were accurate. I’ve lived in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and in the northeast seaport of Dalian. By all reports these centres of foreign investment have been stripped clean of foreign residents.

There could be no tricksy visa incentive strong enough to wipe clean the memory of China’s blanket Stalinist-inspired COVID panic. Nor could there be any sense of security for a foreign national following China’s revised anti-espionage laws which came into effect on July 1 last year.

China has drastically broadened its foreign anti-espionage laws in amendments that legal experts warn could further heighten risk to foreign individuals and organisations operating in the country.

The amendments now encompass anything deemed by authorities to cover national security, and include expanded search and seizure powers, as well as watertight entry and exit bans.

The fact is China’s off-the-hook security apparatus could grab anyone, anywhere, anytime. Before the laws were rubber stamped by China’s parliament, various oblique accusations of espionage were made against foreigners in China, which looked a lot like retaliation for the arrest of a Chinese Huawei executive – and of the two Australians caught in that net, only the journalist Cheng Lei has been released after evaporating into the ether of China’s pre-trial penal system and emerging recently courtesy of the change in government here and a grovelling confession.

Of the academic Yang Hengjun, snatched at the airport in Guangzhou, there has not been a peep.

For the first time since records began, China is being drained of foreign direct investment (FDI), undermining any notion of rude health for the world’s second-largest economy.

This isn’t good, and speaks to the conscious decoupling of formerly ravenous foreign firms who have chosen to de-risk or ‘friend-shore’ their businesses.

Optimistic investors bed against the trend and lobbed a few dollars at China last year, but nearly nine-tenths of it has already been pulled out.

Foreign firms yanked more than US$160 billion in total earnings from China during six straight quarters through the end of September 2023, according to an analysis of Chinese data by the WSJ.

According to BNP Paribas, the collapse in FDI which began in Q3 last year (Exhibit 1) suggests investors are pulling their money from China in the wake of its lurching enmity with the US, its passive endorsement of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and rising tensions around Taiwan.

On that front, the wrong card turnied up again in Taipei after Taiwan went to the polls a week ago.

Tensions of a higher order are most certainly in the post after Taiwanese voters backed William “Troublemaker” Lai Ching-te as its President. China described the vote as a choice between “peace and war.”

And finally this week we learned that China’s population fell by around two million over the last year, a drop double the size as the one the year before.

The demographic mugging of China’s economy is accelerating – which happens when almost one-third of your population joins the senior category within a decade, and when one-fifth of your population is over 60.

And when that population is about 1.5bn, that’s 300mn joining a strained pension system, with an underemployed youth workforce to support them.

That said, Wall Street seems to be willing to wait it out: JPMorgan has forecast that the MSCI China index will have risen 18% by this December from the last, and Goldman Sachs’ targets look similar.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.