Here’s the anti-bear case for why your precious property portfolio isn’t going to collapse

Totally inflated fear. Via Getty

Even as falling home values gather momentum, the Aussie property market bears have woken up and scared the locals too early, says one of Australia’s leading independent fund managers.

Melbourne-based Datt Capital’s Emanuel Datt reckons there’s not enough proof – and not even enough pudding – to confirm house prices are about to start “falling off cliffs”.

Datt’s message to the property bears who’ve been massaging a growing sense of panic is to go back to bed.

Datt runs the Australian focused ‘Long-only’ fundie with his investments largely across listed equity, debt and derivatives solely in Australian markets.

His calls for calm come just as the data property firm CoreLogic dropped its latest quarterly national auction clearance rates, which just happen to show the Sydney auction market at 40-year lows.

CoreLogic blames a “triple whammy” of tepid buyer commitment, fast rising interest rates and persistent inflation.

This morning the Legends at the Bureau of Stats said the annual inflation rate hit its fastest pace of growth of 6.1% (up from 5.1%) with increases in new dwelling purchases help drive that rise, up 5.6% year-on-year.

That puts the central bank further behind in its race to get ahead of inflation.

At CoreLogic, research director Tim Lawless says the property market depression has now spread to the auction market, sending almost every capital city clearance rate lower over the June quarter.

Datt says the bears are ignoring a number of fundamentals that are supportive of house prices. These include unemployment rates at historic lows, a declining rate of housing starts and a high household savings rates.

In fact the value of Sydney housing – Australia’s single largest residential housing market – is down a hefty 3.8% since the Reserve Bank of Australia’s May 5 rate hike.

In two other central markets – Melbourne and Brisbane – the numbers are dropping sharply too, as the new inflation-hating interest rate cycle starts to make itself at home.

However, Datt argues that a core premise of the “bear thesis” is all wrong.

The idea is this – the sudden upward pressure of rising cash rates will flow through via the banks to higher mortgage rates, smashing borrowers who won’t be able to meet payments and will be forced to sell up to stay solvent.

“We need to take a more holistic view,” Datt reckons.

“The rate of housing starts is falling given disruptions to the construction industry, tightening the availability of inventory available on the market. This means that any distressed selling is likely to be on market for a shorter time at the right price point.

“Unemployment rates are at historical lows with increased upside pressure on wage growth. This is supportive as wage growth will be balanced out by more onerous serviceability requirements with future interest rate rises.

“Household savings rates and balance sheets have improved materially since March 2020, buoyed by government stimulus as well as restricted discretionary spending on travel for a relatively long period of time.”

Safe as houses

RBC Capital Markets chief economist Su-Lin Ong is expecting a full-on, peak-to-trough 19% drop in Aussie house prices, warning that’ll leave a reasonably significant mark on our already black and blue consumer confidence, which the ANZ reported this week remains at the deep lows of the pandemic-onset.

But she also said these predicted price declines aren’t even half the nearly 40% increase in house prices since pre-pandemic times.

Either way, what is certain is household debt is at record levels in Australia and most of that debt is held in housing assets.

Ergo sum, (or since my Latin is entirely from Asterix, perhaps ipso facto sic): The household sector is super, super sensitive to the rising cost of debt.

Then there’s inflationary prices for non-discretionary goods (like a lettuce or fresh litre of diesel) and the thought process is – household balance sheets are going to be more challenged as mortgage rates increase.

So far the decline in Aust property prices just looks like a flick off the top. But the speed of the decline so early in an RBA rate tightening cycle reflects the sensitivity (due to high household debt levels) of the property mkt to (rapidly) rising mortgage rates….#ausecon pic.twitter.com/jrUnHhdakL

— Shane Oliver (@ShaneOliverAMP) July 23, 2022

Strength in household balance sheets has been underpinned by high savings, the strong labour market and rising housing prices, the RBA says.

The bank notes that some of the most rate-exposed Aussie borrowers – with fixed-rate loans – are also likely to be able to handle the potential increases in their repayments when their fixed-rate terms expire. Which is within three years at the most.

The RBA says:

- Around 60% of all borrowers currently have variable-rate loans, with around two-thirds of these being owner-occupiers.

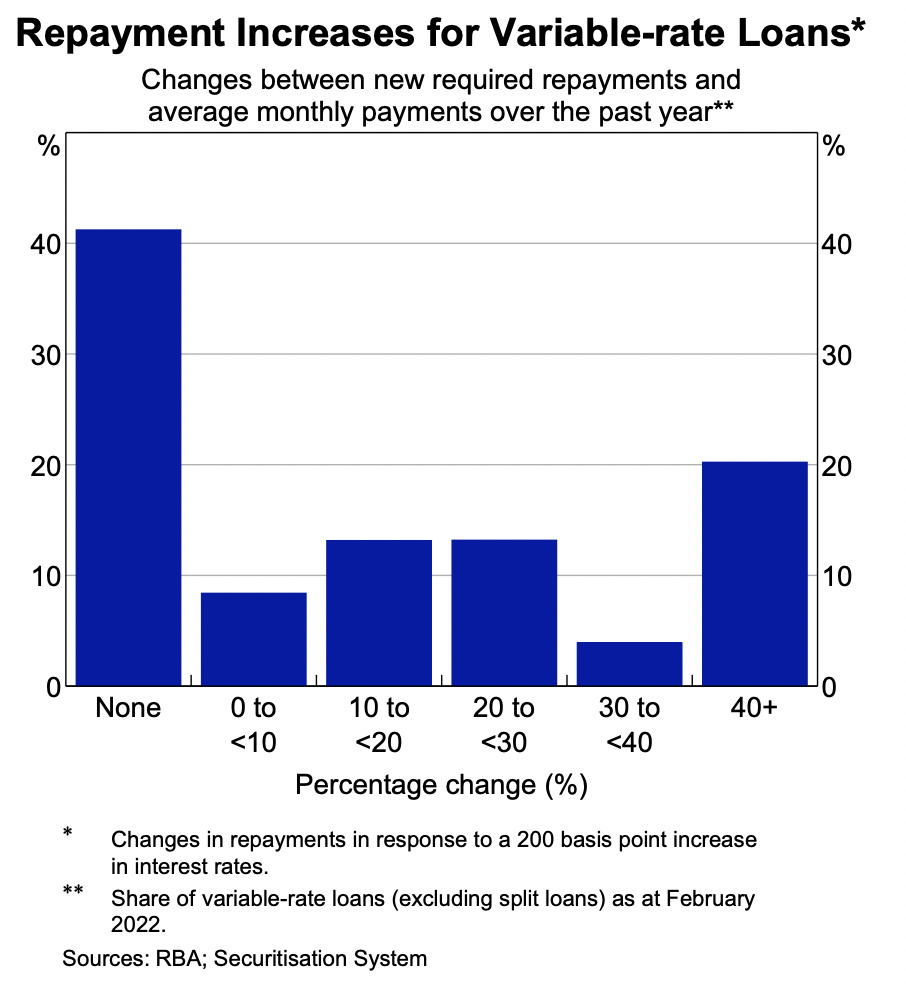

- Recent RBA scenario analysis using information in the Securitisation dataset suggests to them that if variable mortgage rates were to increase by 200 basis points:

- Just over 40% of these borrowers made average monthly payments over the past year that would be large enough to cover the increase in required repayments

- A further 20% would face an increase in their repayments of no more than 20 per cent

- Circa 25% of variable-rate owner-occupiers would see their repayments increase by more than 30 per cent of their current repayments; however, around half of these borrowers have accumulated excess payment buffers equivalent to one year’s worth of their current minimum repayments

According to Emanuel, the RBA puts our household savings at around $260 billion since the onset of the pandemic, circa early 2020.

These savings are in savings, redraw and offset accounts. Since the start of the pandemic, payments into offset and redraw accounts has been around 3.5% of disposable income.

“Taking these savings into account, the ratio of household credit to income is lower than the headline figure of 150% and is actually around the 2007 level.

“Around half of households with variable rate owner occupier mortgage debt have enough prepayments to service their current loan repayments for almost two years,” he told Stockhead.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.