China’s new stock crackdown another bunny from the hat to distract from the elephant in the market

Ta da. Picture: Getty Images

More smoke signals from out of a reopening Beijing. This time we’re being told how China’s porous stock markets are being patched and renovated for what (it seems) everyone hopes will be a deluge of cashed-up, wide-eyed and slightly salivating foreign arrivals.

Disguised as more good ol’ serving of the people, official state media in both Mandarin and English this week have been highlighting the cracking work of local regulators who’ve apparently managed to expel a record number of listed companies from off of China’s mainland stock exchanges throughout calendar year 2022.

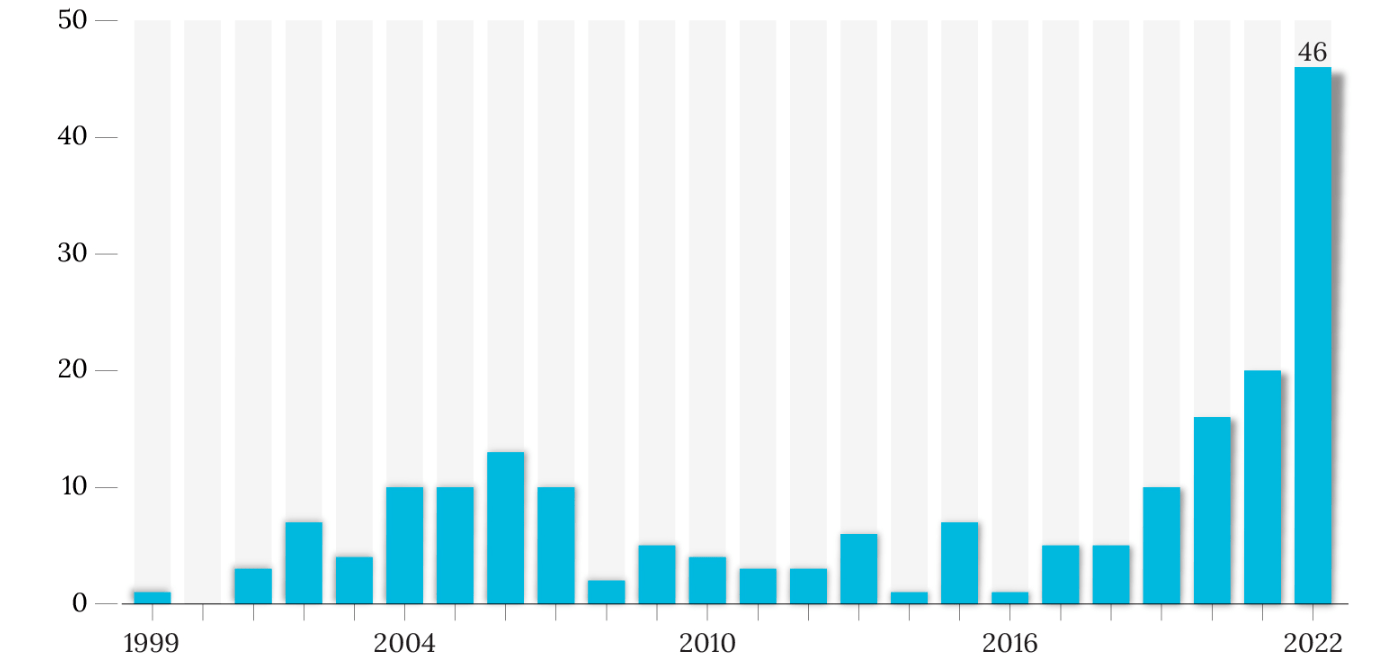

According to the state-run Caixin (“New Fortune”) financial media group, some 42 misbehaving Chinese companies were axed from public life on either the Shanghai or Shenzhen stock exchange over the 12 months to December 31, which Caixin reports is “the highest ever and more than double the figure in the previous year.”

And while Caixin says the ‘vast majority’ were delisted due to poor financial performance, that’s not at all what this is about. In China, the minority is where the action is.

Rules and the illusion of fairness

When Chinese officials leave off recriminating foreign behaviour and instead start broadcasting what they’ve done to curb various local transgressions and extravagances, then the time has come, gentlemen, to start your engines.

Caixin says it’s merely the start.

If you thought the record number of expulsions delivered by a suddenly agile market regulator is a sign of higher standards or greater market operator transparency then you’ll be thrilled to hear that the knives have hardly been sharpened.

Caixin suggests, “(New delistings) could double in 2023, as regulators ramp up efforts to cull poorly performing firms and those that violate the rules or break the law.”

Regulators, roll out

Now, a company can get sliced and diced for just about anything in China, regardless of where it is and what it’s doing.

On paper, and arbitrarily applied, are four “certain parameters” Caixin says which merit expulsion from the mainland’s stock exchanges – financial performance, share performance, compliance and breaking the law.

But with Beijing recently starved of the manna foreign direct investment (FDI), attracting some again is a priority which could help kickstart its COVID-zero-exhausted economy.

And it seems someone has given the regulator a kick along and some of these rules are about to get a public workout.

The trend is expected to pick up further in 2023, state media has warned this week.

At least 80 public companies are in danger of triggering delisting thresholds linked to finances, according to Caixin, and that’s by just doing the math on some Q3 earnings reports, and not on the shady book-keeping.

Or let’s say, the expropriation and nationalisation of the companies Xi Jinping likes the look of. Or the untouchable insiders who may right now be taking all kinds of advantage of their knowledge and access to information.

Volume of delisted co’s from Chinese A-Share Exchanges 1999 – 2022

After his October 2022 ascension to Chairman for Life, President Xi Jinping knows he badly needs an economic win to stop the whispering.

New delisting standards were issued by both stock exchanges back in December 2020, but the effort to sanitise public markets and the behaviour of Chinese companies took a backseat to all kinds of dramas which made the work pointless.

Why improve the overall quality of listed companies by lowering the bar to get kicked off, when the state is intervening on both markets, currency and businesses at leisure?

The Chinese Communist Party under Xi’s leadership has been very comfortable implementing short-notice alterations of regulations, restrictions, censorship, fines, or bans. It’s even happier to arbitrarily draw and quarter the biggest co’s China’s ever produced, to reel in independence and open commerce as a way of reminding everyone where the buck stops.

Under the shadow of bright daylight, Xi had his economic regulators strangulate the “Uber” of China, driving platform service Didi’s headline IPO in the US. It would’ve been the world’s largest ever.

But it isn’t one-way traffic. Not at all. As a political measure in the ongoing China-US trade war, the US may delist ADRs from the US market, in which case the company could buy back the shares, the investor could transfer the shares, or the shares may end up in limbo. Such a delisting happened in 2021 when China Mobile was forced to delist from the NYSE.

Other worries are more general, and more widespread, including less stringent disclosure requirements, looser accounting standards, and regulatory picnics.

The official reasons are usually related to (cyber) security, citizen safety, fair competition, and peculiar social concerns like being “pro-modesty”.

Regulators have been pushing ahead with enforcing the new delisting regime, specifically targeting “bad apples” as well as shell and zombie companies, the head of the listed company supervision department at the China Securities Regulatory Commission (Li Ming) told Caixin.

But the barest minority of the apples are bad. Of the companies delisted, two or three were for being naughty, the rest were just for being broke.

Consider that at the end of December, China had some 5,100 listed companies on its mainland exchanges, with a combined market cap of US$11.5 trillion.

The message of ‘we’re cracking down, but fortunately everyone is good, except this chap, but don’t dwell on it,’ is a familiar party trope.

Anyway, these days more than ever in modern China, most large companies are fully or partly government-owned (through equity or licenses). Every miner needs about 15 mining licences, every car manufacturer needs numerous licences from the government before they can even draw an EV, let alone start production.

All the banks, the Sinopecs, the energy, and raw materials sectors are firmly entrenched under the control of the Chinese state.

Therefore, state-owned companies have a significant economic influence, contributing to more than 40% of the GDP and 60% of the country’s jobs.

In fact, in theory and in the eyes of this Politburo, the Chinese government owns everything: companies, real estate, capital, and workforce. The Chinese state retains and exercises the power to “expropriate”, anything, anywhere, anytime.

Caixin handles it from here:

“Companies who are desperate to stay on mainland stock markets have used a variety of ploys to boost the appearance of their finances. These include cash injections from shareholders, being relieved of their debt obligations, or a reverse takeover by another firm seeking a backdoor listing.

Yet, there is increasingly less room for these firms to maneuver (sic) as exchange regulators have stepped up oversight to deter such practices.

For example, bad-debt manager GI Technologies Group Co. Ltd. (300309.SZ -12.12%) — whose stock is under “special treatment” status, a label given to firms in financial distress or facing regulatory problems — has logged losses for three consecutive years and is nearing the delisting threshold based on its finances.

However, on Dec. 19, the company announced that it was going to receive a cash injection of no less than 700 million yuan from its controlling shareholder, a firm that was established just 11 days earlier.

The Shenzhen Stock Exchange immediately demanded an explanation from GI Technologies about the cash injection, and questioned whether the move was part of any plans to retain its listing status. On Jan. 3, the company issued a statement saying that the shareholder was unable to transfer the money due to issues with fund arrangements.

Clearly the regulator’s work isn’t done yet. In early December, the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges issued three-year work plans to further improve the quality of listed companies, which include further fine-tuning of delisting policies and strict supervision of their implementation.

Amid stricter delisting rules, protection of small and midsize shareholders is particularly critical, according to a recent commentary written by Zhang Wei, a vice chairman of the National Institute of Financial Research at Tsinghua University, and Qin Ting, a senior editor at the Tsinghua Financial Review.

“Small and midsize investors are the most foundational part of the securities market [on the mainland], and their interests are most easily violated,” they wrote.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.