The White House: By every measure China bears have been wrong. This is another way to Xi it

In this series, global equities portfolio manager James White from Lessep IM, ditches micro and macro and embraces “The Meta” perspective.

Lessep IM runs a core portfolio of 40-50 stocks that capture the opportunities in productivity trends and reflect investments in both the drivers of productivity and the beneficiaries of productivity. James also aims to run a long-tail of stocks that have the potential to capture a greater share of new or existing markets.

As with all economies emerging from pandemic restrictions, it can be expected that activity in China will improve rapidly.

The Li Keqiang Index (a measure of economic growth in China favoured by soon to be ex-Premier Li Keqiang, includes loan growth, rail movements, and energy consumption) is pointing to faster economic growth in China; perhaps in the order of 10%.

Yet China’s insistence on a Covid Zero policy suggests expectations of a strong acceleration in growth may be unwarranted.

Many explanations have been offered for China’s reticence to leave Covid Zero to the past. But one explanation, relying on a broader context, rests on this important question: Who owns China? And how does the answer to that question determine the economy’s medium to long-term trajectory.

China’s Isolation

China’s geography and ethnic homogeneity has long shrouded the country in mystery. The first European to make any progress was an Italian Jesuit, Father Matteo Ricci, a Servant of God.

Needless to say, Melvyn Bragg has a cracking little episode all about this utter Sinophile.

Ah yes: Season 17 Episode 27 In Our Time. Simpsonsesque in his longevity.

In the end Ricci was offered the position of Adviser to the Wanli Emperor Zhu Yijun (1563 — 1620), and became the first European unforbidden to enter the Forbidden City.

He was buried in Beijing and is remembered at the South Gate Church.

By the 19th century, industrial superiority made it possible for the European powers to bring their influence to bear on China.

It is a mistake to read Chinese history as a series of peasant rebellions. From the 19th Century these are wars also attributable to Western coercion. The Taiping Civil War (1850 – 1864), a 15 year bloodbath featuring Hong Xiquan who thought he was Jesus Christ’s brother, his peasant army as well as French, British, and American officers. Some 10 million died. Some historians say as many as 30 million.

That’s not one we talk about in the West. The wars that came under a European shadow – the Opium Wars, the Boxer Rebellion – shocking enough in their own way helped etch China’s desire to go it alone into a form of nationalism.

Mark Elvin, a British scholar, highlighted the extent to which China was willing to forego economic development to be left alone. Elvin coined the term “the high-level equilibrium trap”.

Rather than engaging with Europe and following it down the path of industrialisation, China was prepared to maintain its agricultural society. Elvin argues that industrialisation required the destruction of its highly developed, indigenous, agrarian economy and society.

The country was unwilling to pay the price. It had a well-functioning society and culture, perhaps as strong as any, and saw no reason to change. But it was more than economics. China wanted to be left alone.

China’s Opening Up

Elvin argues that the decision to remain agrarian in the early 19th century put China on a long-term path of economic dysfunction. This culminated in the ’70s when Chinese GDP per capita was just $185 in 1977, the end of the Cultural Revolution. In the US, it was $9,453.

As Deng Xiaoping opened China’s economy there was an influx of foreign capital, particularly from Hong Kong. But by the mid-1990s China was on a path to trade, and current account surpluses, that would make its development self-financing. From the economy’s accession to the WTO framework, it has continued to expand its current account surplus and thrive without foreign capital. It has traded with the world, but with near complete independence, reliant on no one.

The Last Decade

China, through its history, has been comfortable, even happiest, as an isolated power. There is no reason to believe that the economic development of the last two decades, no matter how fast, has changed that. This background might explain, in a new light, a number of developments that have occurred over the last decade.

China Bears Have Been Wrong

In 2014, the FT hosted the first Camp Alphaville. On the China panel there was room for just one bull, the remainder of the panel were China bears, the predominant economic narrative of the last decade.

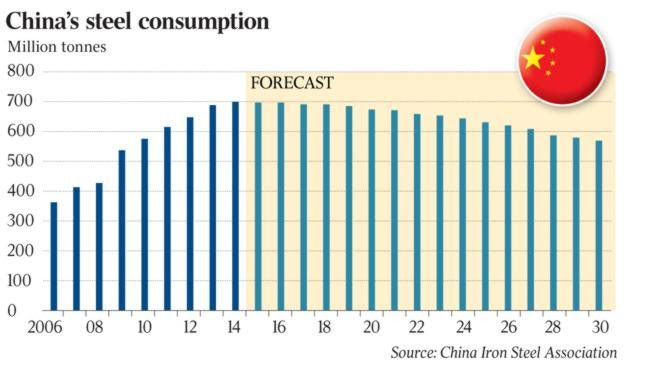

By every measure, China bears have been wrong. The Chinese economy, regardless of faith in internal statistics, has expanded rapidly over the last decade. China’s consumption of real goods, iron ore, Louis Vuitton bags, and apartments in cities around the world, have increased at a compound growth rate in excess of 9% per annum for 15 years. China’s economy has grown faster, unequivocally, than any other economy in measured history. Without an economic collapse.

Yet, the narrative of 2014, has remained the dominant market story. China is, perennially, on the brink of an economic collapse. The debt levels, the consumption of iron ore, and the property market, are all on the verge of collapse, and will take China with them.

It’s fascinating to consider this chart from The Australian in 2014. In 2014, it was forecast that China’s imports of seabourne iron ore would peak at 700 million tons per annum, by 2015, and then decline. In reality, in 2020, China imported 1.2 billion tons.

There has never been a substantial push back against this narrative from China. Indeed, quite often, the Chinese are more concerned than Westerners about the state of their economy. It begs the question; is it in China’s interests for this view to prevail? Absolutely.

Alibaba and Tencent

Regardless of the pace of China’s economic growth, its market size, in the age of the internet would inevitably create online monopolies of considerable scale. With the growth it has achieved, the rise of Alibaba and Tencent, the holding company for WeChat, has been enormous. As we’ve observed in the US, however, such monopolies create a substantial source of political power. Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter is just one example of the political power, online monopolies can bestow.

Famously, Jack Ma, the CEO and founder of Alibaba, once said:

“Be in love with the government. But don’t marry them.”

He also said:

“Chinese consumption is not driven by the government but by entrepreneurship, and the market. In the past 20 years the government was so strong, now they are getting weak. It’s our opportunity; it’s our show time, to see how the market economy, entrepreneurship, can develop real consumption.”

Unfortunately, for Jack Ma, and foreign investors, this will not be the case. Ma, through government intervention, might best be seen (to extend the metaphor) as a former wife of the Chinese government receiving alimony. The political power created by online monopolies has passed back to the government.

There’s a further benefit to China. Alibaba and Tencent remain listed businesses, and very profitable, but you would struggle to find a Western fund manager who would be comfortable taking a substantial position in either company. Again, who owns China matters.

The Small and Medium Size Enterprise

Richard McGregor, the Australian China scholar, wrote Xi Jinping: The Backlash in 2019. The book outlines the change in China under Xi. Of particular interest, is his analysis of the Chinese small and medium sized enterprise sector (SMEs).

The SME sector has played an essential role in China’s development. Indeed, the Chinese, apparently, use a figure “56789” to demonstrate the sector’s impact.

Entrepreneurs contribute 50% of tax revenue, 60% of output, 70% of industrial modernisation and innovation, 80% of jobs, and 90% of enterprises.

This matches the Lessep analysis. The SME sector takes advantage of China’s infrastructure, and public investment, through economic activity in cut-throat competition with each other. These firms are less profitable (50% of tax revenue), but highly innovative (competition is fierce), and account for most activity (jobs and firm formation). Without these firms, China’s investment in infrastructure has a lower return, and the absence of competition creates less innovation and more inflation.

But under Xi things have changed.

In Zhejiang, one of China’s famously enterprising, coastal provinces, the CCP set a target of Party representatives in 95% of SMEs. It is no longer the case, as Xi himself put it:

“Zhejiang has maintained these remarkable results because it is an economy of the grassroots. The common people choose their own development path.”

Not anymore, common people of Zhejiang.

In 2014, Chinese official Lu Wei told Qualcomm executive Paul Jacobs that:

“We should make money together”

JD.com CEO Richard Liu has predicted communism would be achieved in his lifetime and all commercial entities would be nationalised. The Sany Heavy Engineering CEO said his life belonged to the Party.

A strong, and vibrant, SME sector creates a powerful political bloc in China. These moves to control SME management, clearly, consolidate political power in China. For foreign investors, Party ownership, and/or, executive participation lowers the attractiveness of the economy. Again, investment in China is less desirable.

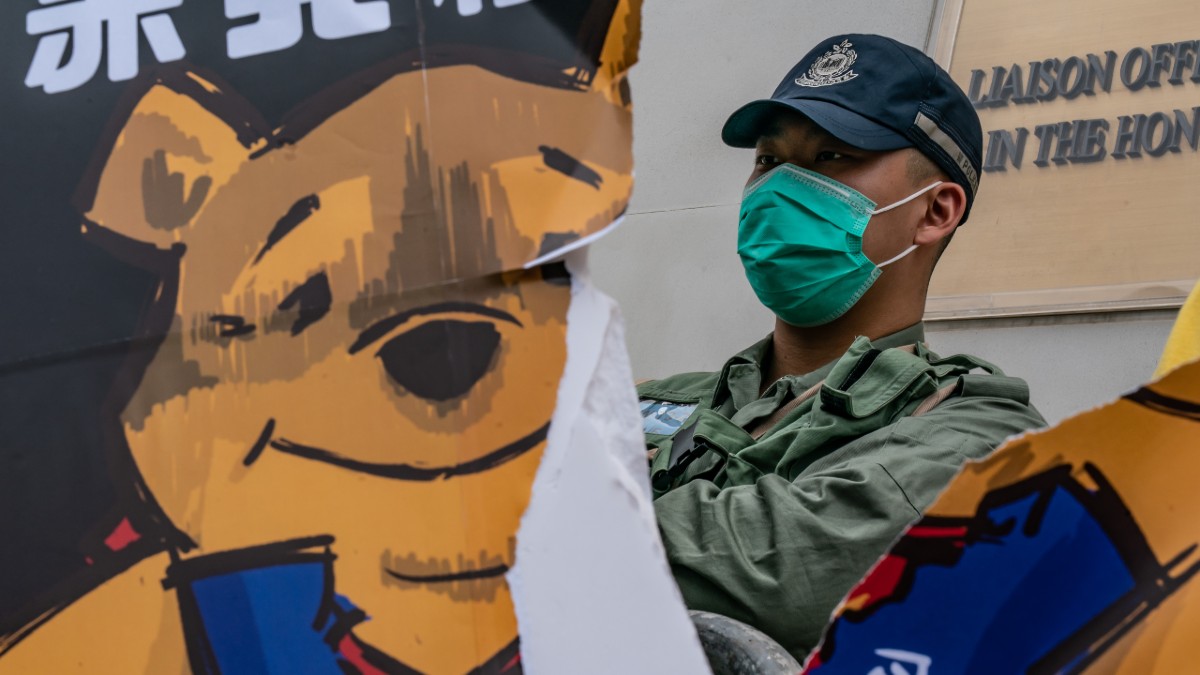

The Plenum and China’s Economic Outlook

China’s recent Plenum consolidated two policies: the integration of the Party into enterprise, and Covid Zero. There is a clear implication that the Party, working with the enterprise, will come with economic ownership. Even in Western companies. Further, Covid Zero, and the necessary quarantine makes Western due diligence over Chinese assets, considerably more cumbersome.

The two policies, from a Western perspective, can be summed up by Harald Malmgren’s tweet, below. China is uninvestable for American corporations.

This is far from an unreasonable conclusion. Government intervention, often arbitrary and capricious, does not provide investors with the certainty they need. The inability to easily observe assets in action, only makes it worse.

Who owns China?

In the 19th century, China’s economic weakness meant its people fought wars with forlorn hope against European powers. The desire for China to remain Chinese was a powerful motivating force. In the first two decades of the third millennium, China has the economic resources to more successfully repel the gweilo or laowai.

China doesn’t want to cut itself off directly from global markets. It wants to continue to export (though more likely to emerging economies) and buy offshore assets. Indeed, in the last week China (there is no longer hiding for China Inc.) has bought a semiconductor company in Germany, and a 25% stake in Hamburg Hafen. Consequently, from China’s perspective this policy of excluding foreign investment will never be formal.

The message, however, as Malmgren has noted, is clear. China is not open to foreign investment. Xi’s policy making, particularly from 2016 has made that clear.

Again, Covid Zero is a blunt instrument of control, but it’s also a further, more elegant statement of policy.

What does the LKQ Index tell us?

In this context, how should we be reading the recent spike in the LKQ Index, if not the recent spike through LKQ?

It should be clear. Through the consolidation of power, and the closing of the door to foreign investment, Xi has created an environment for economic growth to rapidly accelerate on his terms.

The process of shutting the gate to foreign investment required economic restraint. Faster economic growth would have increased the attractiveness of the economy to investors. Consequently, the economy ran slower than required. The ten-year inflation rate has averaged 2% per annum. The chart below from trading economics shows loan growth has fallen steadily from 2012. China has had the economic headway to increase growth, but chose not to, to support political aims.

The Plenum, however, reflects the peak of these political actions. Xi now has the control and headway to allow growth, through policy support, to accelerate.

Early signs of this were seen in imports of coking coal, for steel-making, particularly from Russia.

The last decade was a period of strong, but constrained growth in China, with plenty of bumps in the road. It may be that the next decade for China shows stronger growth, less constrained, but fewer opportunities as a foreign investor.

If this plays out, there is but one place to go for global investors: Australia.

The views, information, or opinions expressed in the interview in this article are solely those of the writer and do not represent the views of Stockhead.

Stockhead has not provided, endorsed or otherwise assumed responsibility for any financial product advice contained in this article.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.