These are the basic facts you need to know about the state of renewables in Australia

The last blow to the renewable energy sector was the disappointing miss on solar and wind energy output in the market operator’s draft ‘MLF’ report.

Before that, it was a slew of changes in 2018 that disrupted commercial plans-in-motion, caused delays and added costs.

The basic facts of the renewable energy generation sector are fairly positive — a surge in generating capacity coming online, increasing government support, and a solid long-term outlook.

But the underlying issues in the industry, the kind that brought RCR Tomlinson (ASX:RCR) undone and could lead to the collapse of others, are ever-present — if usually impenetrable for the layman.

If you’re investing in the renewable energy sector these are the key issues you need to know: the MLF, what politics is going to do and the biggest one, the grid.

MLF — not Milf

As far from the crude teen coming of age movie American Pie as you can get, ‘marginal loss factors’ have rocked energy generators.

MLFs are the energy lost as it moves through the grid, from generator to customer. The stronger or less utilised the grid — the better able it is to take energy from a solar or wind farm — the less energy is lost.

An MLF of one or higher means the grid can take more power than is being generated.

Lower than 1 is bad news: an MLF of 0.8 means 20 per cent of electricity made is lost, and therefore 20 per cent of a generator’s revenue with it.

- Subscribe to our daily newsletter

- Join our small cap Facebook group

- Follow us on Facebook or Twitter

On March 8, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) issued its draft MLF report (later updated for 2019 and 2020), and it’s left a sour taste in the mouths of companies that have suddenly seen their projects’ prospects suddenly downgraded.

Four sites were given MLFs of sub-0.8: the only ones with a listed owner are the Silverton and Broken Hill wind farms, owned by AGL (ASX:AGL).

Other ASX darlings such as Windlab (ASX:WND) have wind farms assigned MLFs between 0.8 and 0.9, while Tilt Renewables’ (ASX:TLT) farms are in the 0.9s. Genex’s (ASX:GNX) Kidston solar farm has an MLF of 0.86.

Some areas are penalised more than others, or as one analyst said at the Wind Industry Forum in Melbourne last week, “anything north of Gladstone is a disaster zone”.

And companies are not clear on how these numbers are being obtained.

Pacific Hydro project manager Rachael Cox said banks had been “all over this” for 12 months but it was frustrating to suddenly lose 10 per cent of your income.

“I’m looking at my general manager who probably wanted to cry when she read that report… we called that day Black Friday,” she said at the forum.

“We certainly didn’t forecast the numbers that came out.”

Politics matters, now

Federal Labor promises to bring in a 45 per cent emissions reduction target by 2030, to re-introduce the National Energy Guarantee (NEG) and if they can’t cobble together support for that, use the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) to contract projects out on the government’s behalf.

Green Energy Markets director Tristan Edis says a 45 per cent emissions target will require a huge surge in renewable energy capacity, over and above the 26,000 gigawatt hours (GWh) coming in by 2021.

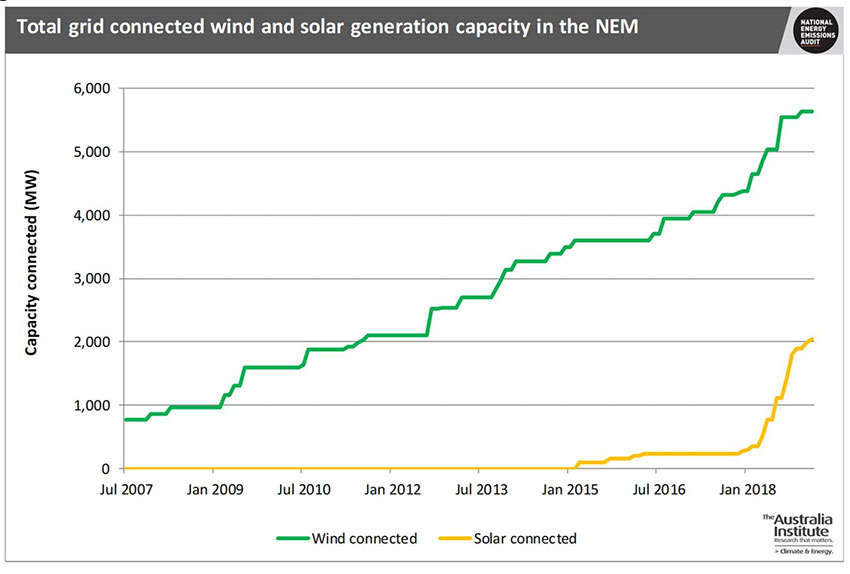

Renewables including rooftop solar, according to the Australia Institute’s March National Energy Emissions Audit, already make up 21.2 per cent of the east coast and Tasmania’s national energy market (the ‘NEM’ — WA and Northern Territory operate separate markets).

Mr Edis expects all of that extra capacity coming on by 2021 to push wholesale prices down to possibly levels last seen in 2015, before the Hazelwood in Victoria and Northern in South Australia were shut down.

Then, wholesale prices hit $20-40/MWh.

Mr Edis also warns that if a Labor government tries to use the CEFC to further its renewable energy aims, an explanatory memo to the Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act 2012 says the organisation is supposed to make a commercial return on investments.

And there is also the risk that a CEFC-funded project — direct government contracting — simply creates power generation that isn’t exposed to market vagaries and ends up pushing private companies out.

The Grid

Finally there is the all-important grid, the transmission lines that distribute electricity around the NEM.

This is all tied up with those MLFs.

Parts of the grid were set up to take a certain type of power, in particular those around coal-fired power plants. But where solar and wind farms with their intermittent power are rapidly being set up, the grid may not be equipped to accept and deliver that kind of energy.

AEMO can ascribe worse MLFs to a weaker grid or a location where more projects are connecting to it. It can also curtail the amount of energy a project can deliver.

Already Windlab has lost a major investor because it couldn’t price the risks “associated with the project’s grid connection, including risk of network losses and risk of curtailment”.

And AGL’s 200 megawatt (MW) Silverton wind farm is only allowed to produce up to 75 MW of power at any one time, and if the Broken Hill solar farm is operating it’s only allowed to produce 45 MW of power — a massive cut to its operating ability and revenue potential.

There is no national plan to organise the grid network, but last year AEMO produced the Integrated System Plan (ISP) which was the first attempt at a version of east coast organisation.

“The big fat pipes are down in La Trobe [in Victoria], and the little skinny pipes are up in Mildura. Unfortunately that isn’t where the sun and the wind are,” Ausnet Services’ (ASX:AST) Dennis Freedman said at the wind energy forum last week.

“50 or 100 GW of renewables needs to come and currently we can’t take it…. The ISP gives us the opportunity to move the electrons to where they need to be.”

The short term outlook for renewables is rocky as the industry struggles with five AEMO rule changes in nine months around grid connections, a looming oversupply, and a potential Labor government promising even more.

But as aging coal plants, such as Liddle in NSW, shut down and as both policy and the market operator become more savvy, it’s expected the long term payoff will be worth the short term pain.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.