Govt catches up with industry, gets to work on offshore wind regulations

Pic: Thana Prasongsin / Moment via Getty Images

Two months after testing began for Australia’s first offshore windfarm, the government has released its proposals for how it plans to regulate the new sector.

It’s proposing 30-year licences and adapting the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA) to also regulate the nascent sector.

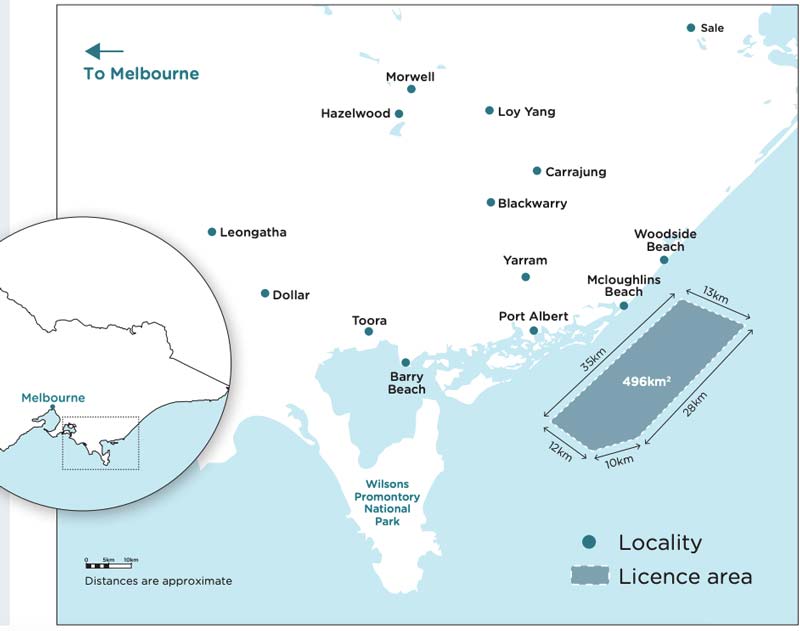

In November, Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP) began researching wind and wave conditions and environmental impacts in a 496sqkm area off the south coast of Gippsland, to lay the groundwork for an $8 billion project name ‘Star of the South’.

This week the Department of the Environment and Energy issued its discussion paper on the way it wants to regulate the new sector. Public submissions are due by February 28, 2020.

Long-term commercial licences are on the table to provide certainty for developers, with the right to transfer them to other pre-qualified parties.

A 10-year non-commercial licence will be available for demonstration projects using new technologies such as wave or tidal concepts.

NOPSEMA is slated to control licensing of farms as well as of associated infrastructure such as transmission lines.

The licensing won’t cover existing projects, which at the moment consists of Star of the South.

The southern star

The CIP proposal is for a 2.2 gigawatt (GW) farm which would have the capacity to power 1.2 million homes or about 18 per cent of Victoria’s power demand.

It’ll connect to a point in the La Trobe valley, an area where the grid is particularly strong as it used to support the 1.6 megawatt (MW) Hazelwood coal power station, and still transmits power from the 2.21 gigawatt (GW) Loy Yang A, the 1.07GW Loy Yang B, and 70MW Yallourn coal power stations.

It is expected to cost $8-10 billion, or about double the per-megawatt cost of an onshore wind farm.

Several projects have tested or are testing wave and tidal power around Australia as well.

Sydney-based MAKO Tidal Turbines has a demonstration turbine at Gladstone in Queensland; The Australian Tidal Energy project (AUSTEn) is funded to look at sites; and most spectacularly Carnegie Clean Energy called in the administrators in March 2019 after losing funding for its years-long attempt to make wave energy work.

READ MORE about offshore wind:

Has the time come for offshore wind power to take its place in Australia?

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.