What happens when AI music tools infiltrate the art of songwriting?

Pic via Getty Images

Listening to your favourite songs is akin to sightseeing in the places you know best. Press play on a treasured recording and you’re cruising the streets of your town accompanied by tunes that remind you of who you were, who you are, and who you yet might be.

Not so long ago, the only way to hear music was to be physically near the sound of live performers. Recording studio technology allowed for the replication of songs to be packaged and subsequently sold on vinyl, cassettes and compact discs, and as computer files.

Today, most of humanity’s collective musical endeavour to date has been encoded into phone apps that fit snugly in your pocket and can be dialled up at a moment’s notice.

Music offers an endless process of discovery, renovation and reconstruction, and much of the joy in listening is in finding new avenues down which to sightsee.

But in recent years, plenty of flesh-and-blood songwriters have become concerned by the way their talent for writing memorable tunes has been short-circuited by technology.

Soon, they worry, their art will be molested by artificial intelligence tools that boil their hard-earned methodology down to component parts to be strip-mined by anyone. Some fear that very thing has already happened.

If anyone or their grandmother can write a song that sounds like your favourite artist by typing a few words into a text prompt in an AI-powered app — then waiting a few seconds to hear what it spits out in response — doesn’t that rob the act of songwriting of its meaning and purpose?

If so, what’s left behind for the sightseers?

The quest to answer those questions began last May, when I sat down with one of Australia’s most acclaimed songwriters, Nick Cave.

Near the end of our two-hour interview inside a plush Sydney hotel meeting room — amid a national tour of sold-out concerts — he surprised me by steering the topic of conversation in a new direction.

“Have you checked out any of the AI stuff?” asked Cave, 67. “There’s a song generator thing called Suno, have you looked at that? It’s insane, and it’s deeply troubling.”

Cave told me he’d been alerted to this new tool by a reader of his Red Hand Files email newsletter.

Suno’s homepage invites visitors to “make any song you can imagine” by typing a few words into a little comment box. So Cave did just that.

“I went on the app, and wrote, ‘Dark, slow, gothic song about a banana,’ right?” he said. “And within 15 seconds, it spat this song out, called The Dying Peel. It was good; it had a good chorus. It wasn’t great. It even understood that there’s a sort of joke going on about the dark gothic song on the banana — that you were taking the piss a little bit — so it talks in all these extended metaphors about the blackening of the skin, and all this sort of stuff.”

[To listen to an example of the banana song Nick Cave created using Suno, click ‘play’ on the song embedded below.]

“It was amazing, right?” said Cave.

“Initially, it was amazing. And then, I put in ‘a death metal song about the Rape of Nanking’ or something like that. That came out — but by halfway through it, I lost interest in it. It was just this thing that could do this stuff, right?

“But the thing is that it’s good; it’s kind of bland, but you can see the direction of it.”

[To listen to an example of the death metal song Nick Cave created using Suno, click ‘play’ on the song embedded below.]

Having proudly devoted much of his life to the painstaking art of pulling songs out of thin air and committing them to record with his bandmates in The Bad Seeds, Cave was hit by a wave of depression, then nausea, as he got a first-hand look at what this technology threatened to do to his craft.

“It really shows the intent of AI, in my view; or these sorts of song generators, in particular,” he said. “The idea that we are broken people that are able to sit, and create amazing and awesome things, is completely swept to one side, and we’re simply given the commodity itself. That’s its intent: to completely sidestep the inconvenience of the artistic struggle (by) going straight to the commodity. Which reflects on us, as what we are as human beings: things that consume stuff. We don’t make things anymore; we just consume stuff.”

It was clear he’d been thinking about this subject for a while. Perhaps he wanted to air these ideas with someone other than his manager, who had attempted to reassure this master songwriter that people would continue wanting to hear “the real thing”, rather than a digital facsimile fed through a machine.

“I’m not so sure about that,” Cave said, frowning. “I’m an enormously optimistic person about the world, in general, but I just think the demoralising effect, or the humiliating effect that AI will have on us as a species will stop us caring about something like the artistic struggle.

“That we will just accept what is fed to us through these things; that we will be in awe of the banal.”

“That’s to me the direction that it’s going,” he continued. “Suno is utterly banal. There’s no soul or spirit or anything — it’s just a computer-generated song that may be good, but…” He paused, then admitted, “I find it quite terrifying.”

“No-one seems to be worrying too much about bands going in and using ChatGPT to write their lyrics and stuff like that. It feels like it’s just sliding towards that effortlessly. For me, the terrifying thing is not that it’s happening – is that it’s just happened. It’s happened, and anyone can use it.

“The argument is that it’s this ‘democratisation of art’, and that your grandma can now make a great song, and that in the future, everyone will be able to make a great song — but it’s actually a lie,” he said. “The future is that no-one will be able to make a great song; it’s just this machine will be able to do it. I find it all unbelievably disturbing. I’m not worried about my own job, or something like that. I’m not worried about being replaced; just what it’s saying about us, as human beings.”

Cave’s provocative, impromptu opening of that particular can of worms prompted me to raise this subject with a handful of other A-list composers — three more Australians, and three internationals — across the ensuing months, to take the temperature of the artistic community as the heat continued rising. But before we go there, some brief background is helpful.

Suno’s welcoming prompt — “make any song you can imagine” — is powered by technology known as generative artificial intelligence.

The text box into which you, your grandmother or any other budding songwriter can type a few descriptive words is the proverbial tip of the iceberg; the enormous, unseen mass beneath the surface is the AI supercomputer.

Pretty impressive, right? But how does a supercomputer learn to make a dark, slow, gothic song about a banana? Machines aren’t inherently creative, so there’s only one way for them to make something new: by listening to something old.

In simple terms, that supercomputer has sucked up a vast amount of material; millions of existing melodies, lyrics, rhythms, arrangements and compositions, in whole and in part. It’s then undergone intensive training, using machine learning, to recognise patterns and, in time, come to understand how we humans make songs, so that it can faithfully produce new works based on familiar sounds.

It’s these interrelated acts of listening, learning and producing that have shaken the music business to its core, and the aftershocks are ongoing.

The famed Silicon Valley ethos coined by Mark Zuckerberg in 2012 — “move fast and break things” — is also driving the brains behind generative AI music companies such as Suno and Udio, two start-ups which are the market leaders in this space.

Naturally enough, that ethos has managed to mightily piss off an entire ecosystem of music rights holders, from record labels and publishers to songwriters and producers.

In August, Australia’s music rights body APRA AMCOS issued a landmark report, titled AI and Music, which floodlit this issue for our national music industry.

By collecting 4200 responses from songwriter, composer and publisher members of APRA AMCOS, the motive was to build a groundswell of support that would hopefully prompt government bodies into defining guardrails on the use of AI technology, so as to protect artistic livelihoods.

The report revealed that 82 per cent of Australian music creators were concerned that the use of AI in music could impact their ability to make a living from their work, while 97 per cent of respondents demanded that policymakers urgently address this matter while AI tools are still in their relative infancy.

In monetary terms, the report also estimated that, within four years, 23 per cent of music creators’ revenues will be at risk due to generative AI, representing an estimated cumulative loss of about $520m.

Suno and Udio are both being sued by the Recording Industry Association of America — aka the RIAA; the US equivalent of our ARIA — in a lawsuit filed in June alleging widespread infringement of copyrighted sound recordings.

In a response filed in August, Suno’s lawyers explained the app’s training data “includes essentially all music files of reasonable quality that are accessible on the open internet, abiding by paywalls, password protections, and the like, combined with similarly available text descriptions”. Both Suno and Udio used the same law firm for their responses; both companies claimed that their use of copyrighted materials fell under the “fair use” exemption to US copyright law.

This case hasn’t yet been heard in court, and will continue to be closely followed by industry workers, particularly since it’s the three major record labels — Universal, Sony and Warner — who chiefly represent the interests of the recorded music business under the RIAA umbrella, just as ARIA does on our shores.

Few things get artistic people talking more than the threat of their creative essence being stolen from them and commodified by technology companies without adequate recompense.

When APRA AMCOS issued its report last year, Australian singer-songwriter Tina Arena came out with both barrels blasting against what these tools represent for her and her colleagues.

“If you want to be a part of it? Knock yourself out,” she told me. “If you don’t … you should not be forced, in a tyrannical fashion, to follow suit because some guru in Silicon Valley thinks that this is the great next thing.

“While they may stand to make an absolute fortune, it is absolutely abhorrent that they would put people’s livelihoods at risk and not give a f..k,” said Arena, 57. “I mean, who the f..k do these people think they are? This is not ‘artists whingeing’. Artists make nothing, and they pay tax. Those corporations get bigger, fatter, richer, and don’t pay any tax. F..k off. Enough.”

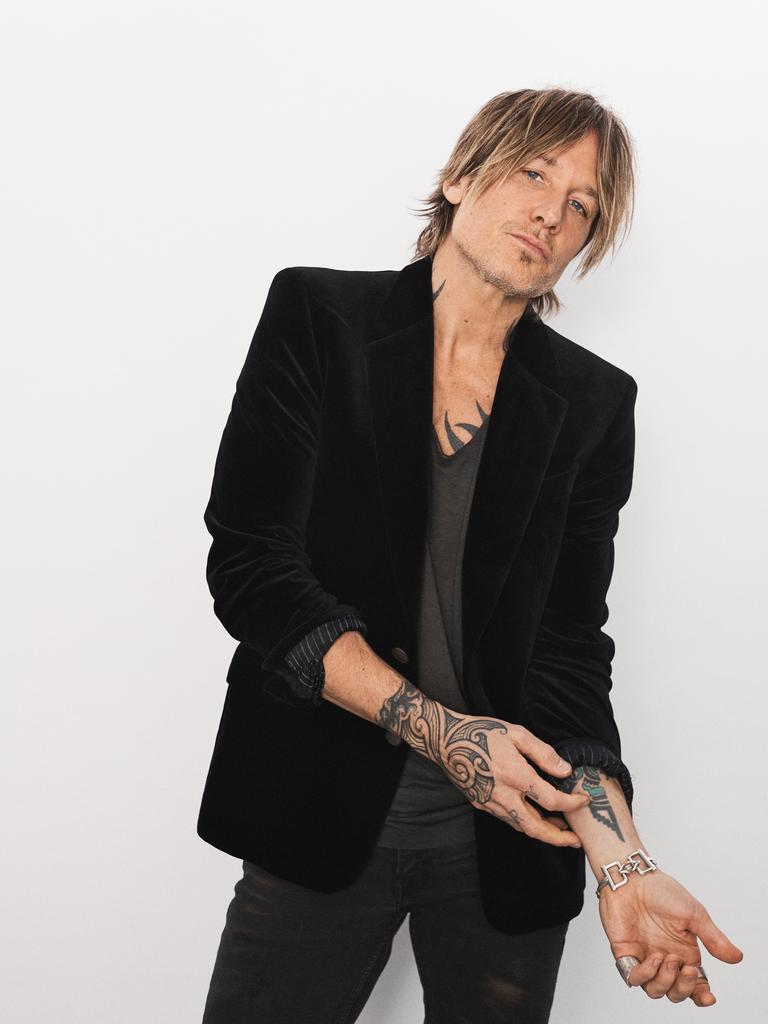

When I raised the subject of AI in an interview with Keith Urban last September, he replied, “The jury’s out on it right now, in the sense that it’s brand new. It’s definitely something to be very awake for,” he said with a laugh.

“I mean, we all saw (2023 film) Oppenheimer; it’s just important that enough adults stay in the room, to keep an eye on things — and transparency is really important, so we actually know what’s happening,” he said. “Hopefully we’ll always want to feel a human connection. That’s separate to it being used as a writing tool, and things like that. I don’t know how that’s all going to play out.”

The NZ-born, Australia-raised and US-based country star then offered this curious behind-the-scenes anecdote.

“I know that in Nashville,” said Urban, 57, “All the publishing companies sent memos around to all the staff writers saying, ‘Do not use any AI when you’re writing songs, please’ — because writers were just getting lazy. ‘Ah, we just need a second verse and we can call it a day…’ ” — he mimed typing a few words into a software prompt – “ ‘Boom, there it is; good, done’.

“And of course, what was happening: these songs were being turned in, the song gets released — and whoever the AI company is, they see it, they know the IP address, they know that that series of words was used that day, in that town. ‘Hmm, interesting; we co-wrote that song.’ Then they’re after copyright, as writers on the song.

“So the publishers were saying, ‘We’re not having a whole bunch of people suddenly be writers of the song that weren’t in the room … Write your (own) f..king song!’” he said with a laugh. “Do your job! You’ve got one job to do!”

In September, when I spoke with Winston McCall — frontman of Australia’s biggest heavy metal export, Parkway Drive — he found the topic more amusing than threatening to the livelihoods of he and his bandmates, whose ferocious style of music has seen them selling hundreds of thousands of tickets to their spectacular live shows when touring Europe and the US.

“It’s f..king soulless,” said McCall, 42, with a laugh. “I’ve no desire to use it at this point in time. The fun part for me of creating music is creating music, and not getting a computer to do it. I love creating art; I don’t need a shortcut.

“At the same point in time, I think the ethics behind it are really shithouse: it’s just another thing where you’re ripping a bunch of people off who’ve actually put time into creating things,” he said.

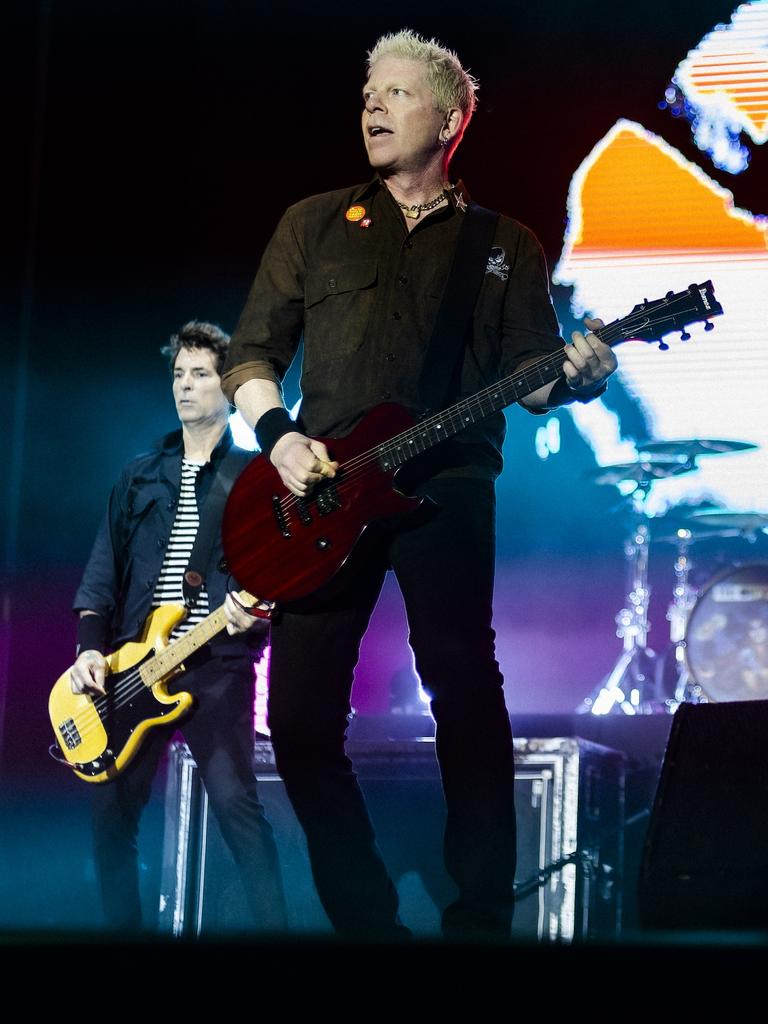

Beyond our shores, when I spoke with Bryan “Dexter” Holland — frontman of the mega-selling US punk rock band The Offspring — in November, he had some hands-on experience to share.

“AI is such a charged subject, right?” replied Holland, 59. “It is a very scary idea, and I get how it could be; I don’t want to boo-hoo it, but I think that (fear) might be a little premature in certain areas. In songwriting, for example, our producer Bob (Rock) and I were talking about how people claim they’re writing songs with AI, and he goes, ‘I think we should try it’.”

Holland and Rock turned to face the strange, as it were, and decided to feed ChatGPT the lyrics of one of The Offspring’s most popular songs — 2008’s You’re Gonna Go Far, Kid, which has amassed 1.1 billion Spotify streams — and asked the tool to improve the lyrics.

“And granted, this is just lyrics, it’s not music — but it spit something back out, and it wasn’t good at all,” said Holland with a laugh. “It was either too close to the original line-by-line, or it didn’t make sense, or there was no insight; no humanity, certainly. No feeling to it. So I thought, ‘I think we’re safe in music on the AI front — for now’.

“I might be underestimating the potential for evil, but I feel like this is going to fall into the category of other technologies that have come before, where it can be used for good, or used for bad,” he said. “It’s going to, again, come down to us to decide how we utilise it.”

Another culture-shaping singer-songwriter in Billy Corgan — the frontman of defining 1990s-era rock band The Smashing Pumpkins — projected a little further into the future when asked if he had a position on this subject, and also conducted a little meta-commentary on music journalism.

“It’s here; it’s not going away — it’s like arguing about electricity,” said Corgan, 57.

“It is going to influence every part of human life that you can imagine. Because invariably, if you continue in this career of writing, 10 years from now, you’re going to be having to make a choice between an artist that is completely an AI construction: you know it’s an AI construction, but you like it — or everybody else likes it, which forces you to write about it.

“Then there will be a whole group of artists that will say, ‘We’re purists. We don’t use it, we don’t want it — and in fact, we don’t even use (audio processing software) Auto-Tune. We just want to be human’. And you have to make a decision of whether or not you want to support art which is not created the way it’s been traditionally created for most of human life.”

“I have no interest in using it, and won’t use it,” said Corgan of AI songwriting tools. “It’s not a moral position. I’m good at what I do. God gave me an ability, and that’s it: I don’t feel I need to supplement it by cheating my way forward.”

The head Pumpkin concluded his future projection, however, with a deadly serious warning.

“But I know for a fact that soon, I will be competing with people who are going to not only cheat their way forward — they’ll f..king kill their own mother to get forward,” he said. “Do you think they’re going to stop at Go — to use the Monopoly analogy — about using AI to game the system? Get the f..k out of here. That shit’s over.”

The final word should belong to Academy Award-winning screen composer Hans Zimmer, who referred to one of his touring musicians — British guitarist Guthrie Govan — when asked in January about AI.

“I’m so not interested in a machine replacing him,” said Zimmer, 67. “Why would it be better, if Guthrie can do what he does — which is have me somewhere between a state of weeping and laughing; between being completely gobsmacked and completely happy that a human being exists that can do that?”

“OK, there are not all that many that can do that,” he continued. “But wouldn’t it be nicer if everybody aspired to becoming really good; becoming soulful; becoming an extraordinary musician, an extraordinary communicator, and an extraordinary human being at the end of the day — as opposed to leaving it to teaching machines how to copy?”

“Because that’s really what it is: it’s a learning machine. Yes, there will come the point where it will become self-cognisant and will start making up its own stuff, et cetera,” said Zimmer, who began smiling as he said the next sentence. “But I tell you what: it’s not going to take you out for a beer — and with Guthrie, that is an important point!”

Earlier I compared the notion of relistening to your favourite songs to sightseeing in the places you know best.

That metaphor isn’t mine: it was written by another intelligence, one belonging to American writer Warren Zanes, which he introduced in the closing pages of his excellent book Deliver Me From Nowhere, published in 2023.

“Novels we might read twice, generally once,” wrote Zanes. “Movies we might see a few times. Our favourite recordings? We can listen hundreds, even thousands of times. They go through our systems in a very different way. A great recording, listened to hundreds and hundreds of times over a period of years, even decades, can suddenly open onto a new vista or back alley. The medium is dense. And, obviously, whatever one is going through in life triggers that density in different ways.”

I read this book on a whim last winter, having had it recommended to me by two people in my life whose taste I value greatly. Both of them were right to direct my nose toward its pages: its narrative — centred on the circumstances that led Bruce Springsteen to writing and recording his minimalist 1982 album, Nebraska — walloped me and left a deep imprint, particularly that haunting closing image of cruising through the streets of a town you know well, while looking at passing houses and wondering what goes on inside.

“Sightseeing in the place you know best,” wrote Zanes. “That’s what listening to great songs and recordings is like. Some would say that the special ones are just better for sightseeing, even if you think of them as your own backyard. Songs like (The Rolling Stones’ 1965 single) (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction. You could drive past that sucker a thousand times and still come up with new ideas about what’s going on in there.”

While writing this essay, having spent nine months speaking with world-class musicians on the subject of artificial intelligence, I didn’t draw a single connection between Zanes’ book and AI — until one Friday afternoon in February, as I drove home from a local takeaway store while listening to a Bruce Springsteen podcast interview.

This was a route near my backyard I’d taken hundreds of times previously. Yet when that thunderclap of inspiration and creativity hit me — unbidden, but most welcome — I suddenly saw a way to weave together several unrelated strands, and that’s what you’re reading right now.

“Career songwriters know how people consume music because in most cases that’s where it all started for them, as consumers themselves, falling in love with songs, playing them over and over,” wrote Zanes. “So they know that if they write a good one, someone out there will listen on repeat. For the songwriters like Springsteen, the song is created as a thing to be visited many times. So make it ready for the sightseers.”

Writing about writing can be tedious but I’ve opted to do so here in the hope that it illustrates a central idea regarding intelligence, creativity and making art that stands the test of time.

Millions of people love the music created by the artists quoted in this story — as well as the stark songs of Nebraska — because they connect to parts of ourselves, both familiar and unfamiliar. We revisit their work because although the recording remains the same, we change. In time, our understanding grows as previously unseen vistas reveal themselves, sometimes in a sudden thunderclap.

That there is a gap between music created by AI, and by us, is to be treasured. For now, the best that AI-influenced songwriting can offer us is to create novel sonic equivalents of display homes: pleasant, empty shells whose furnished interiors are staged to mimic the look of lived-in dwellings while offering none of the character or meaning that warrants further inspection.

At a glance, we see that sucker and keep on driving.

This article first appeared in The Australian.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.