Ultracharge signs deal with $6b chemical maker to supply lithium battery material

Pic: Getty

Ultracharge has signed a partnership with one of the world’s biggest chemical companies to produce the juice that makes up its lithium battery anode.

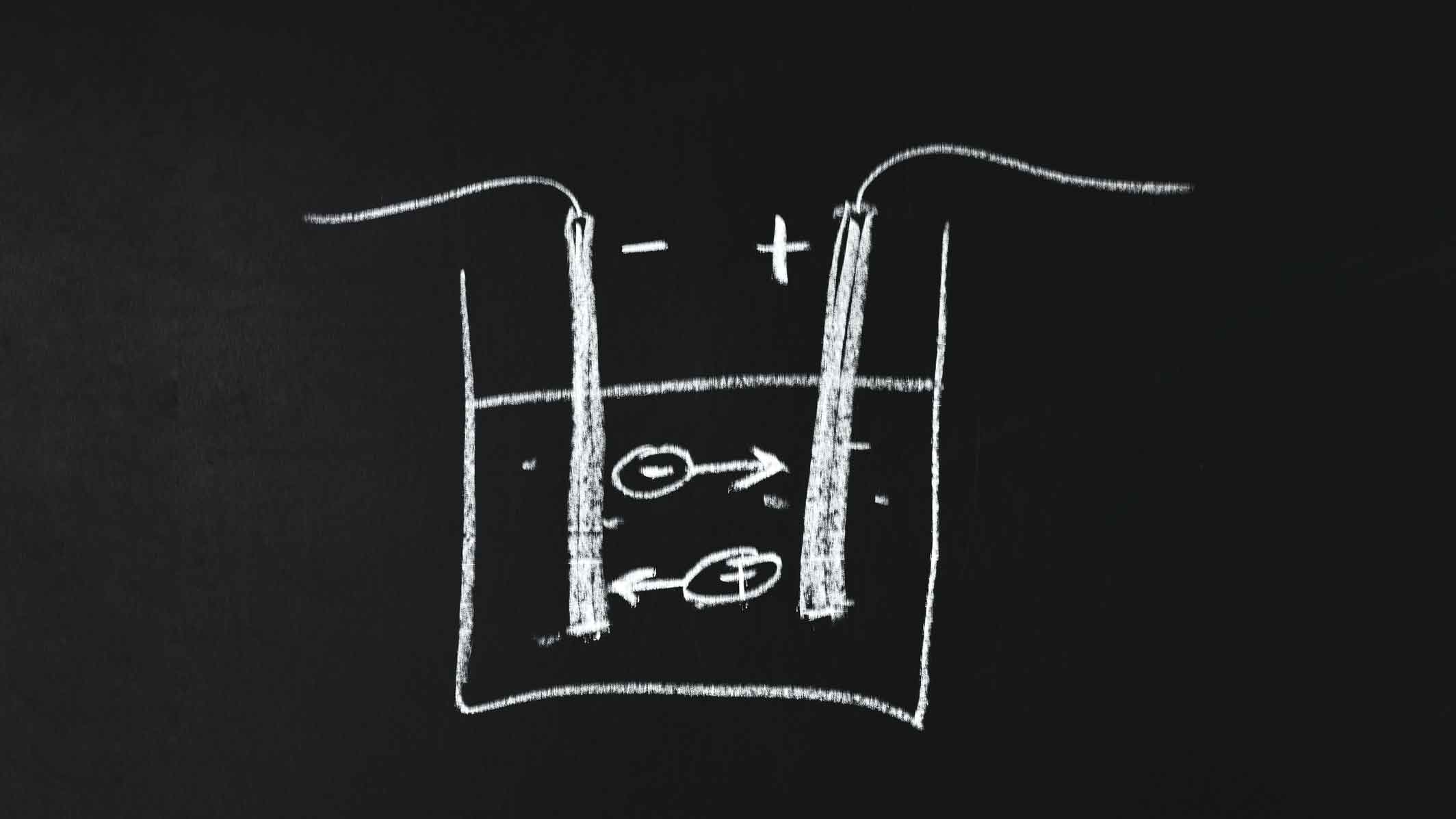

Under the deal with $6 billion US company Chemours Ultracharge will make the titanium dioxide anode material (the negative terminal in a battery).

The Intellectual Property for a titanium dioxide nanotube anode is Ultracharge’s (ASX:UTR) main asset, but it also has rights over flow battery and high voltage cathode technology. The cathode is a battery’s positive terminal.

The Chemours deal was picked by analyst Marc Kennis from TMT Analytics, who wrote earlier in October that one of Ultracharge’s three commercialisation options was partnering with a major chemical maker such as Chemours, Tronox or Cristal. The latter two are in the process of merging.

Mr Kennis told Stockhead the deal would help ease the path to commercialisation, because Chemours had the deep pockets and expertise needed to get the tech out of the lab.

The other options were licensing the technology, or going it alone and sinking considerable capital into large-scale production facilities.

The deal meant a two-year commercialisation timeline was likely, whereas it would have taken much longer, and been much more expensive, if they’d tried to do it by themselves.

Ultracharge said on Wednesday that it was postponing a capital raising because of the deal, so the news could be fully absorbed by the market.

Chief Kobi Ben-Shabat told Stockhead he was on track to start small scale pilot supplies of the anode material from Israel by the end of the year — but volumes would initially be low.

With commercialisation of the nanotube technology still two years off, and future clients still to be nailed down, Mr Ben-Shabat says revenue will come from another technology — the cathode.

Ultracharge bought the rights for a high voltage lithium manganese nickel oxygen cathode earlier this month for $US200,000 and up to 90 million shares. The tech is half the cost of commercial cathodes and has greater energy capacity.

Mr Ben-Shabat says this should fast track revenue generation within 18 months.

The cathode also gives the company the ability to eventually make a full battery.

Risks and rewards

As with any battery technology there is a risk in getting a lab-based concept to work as a commercial product.

But Mr Kennis said the deal with Chemours had reduced risk.

The nanotube tech itself comes with some strengths and some weaknesses, he wrote in a research report.

It charges faster than a graphite anode and has a longer life, and compared to other lithium titanium oxide options it’s lighter and cheaper.

Crucially, it’s also safer than flammable graphite and further work should improve the energy density, or the amount of energy that can be packed into a nanotube.

But compared with specs from graphite, the titanium dioxide anodes don’t stack up well.

“Compared to graphite anodes, TiO2 nanotube anodes will likely remain more expensive. Lower operating voltages of TiO2 nanotube anodes implies the use of more cells or a different cathode technology will be required to achieve a similar voltage output,” Mr Kennis wrote.

Cancelling more shares

Ultracharge may be at the end of a long-running process to rectify an early misstep: a backdoor listing when the ASX tightened up the rules around changes in business activity.

In May last year Lithe Resources bought Ultracharge and was immediately suspended from trade for proposing a change in business activity without shareholder permission.

It wasn’t reinstated until December.

The price Lithe paid was 486 million shares, or about $24 million.

“As the company was suspended from trading from the date of announcement of the proposed acquisition until reinstatement, there was no opportunity for the market to provide price discovery or any signal as to whether or not the market considered that the acquisition on the terms disclosed was likely to be value-accretive,” Ultracharge said in February this year.

Investors and advisors believed the price was too high — the company’s shares sank from 5.9c as a resources company to around 3c.

Ultracharge’s shares closed Wednesday at 3c.

In February the company started cancelling shares that had been paid to the sellers of Ultracharge and entities that had facilitated the deal.

“The company proposes to cancel approximately 129.2 million shares, comprised of 40 per cent of each cancellation shareholder’s holding and approximately 17.2 per cent of the ordinary capital of the company,” it said in February.

On Wednesday it said it was seeking shareholder approval to cancel another 28.6 million shares, or 4.5 per cent of the issued capital.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.