The tiny pianos that keep playing even in cryogenic storage

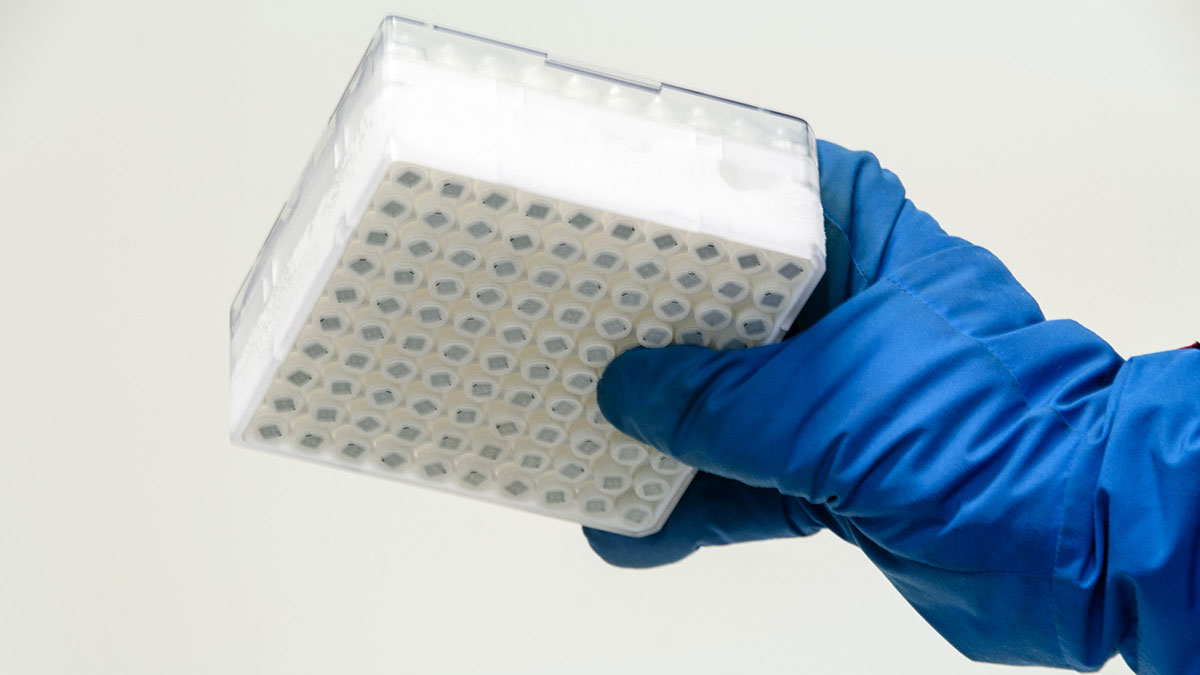

Pic: nespix / iStock / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

An Australian professor who set out to fix the “frozen chicken problem” was struck one day by a novel solution – a tiny piano that keeps on playing even in extreme temperatures.

The idea came to Dr Ron Zmood, a Melbourne inventor and former RMIT professor, after he heard about problems faced by food companies trying to ship frozen produce.

Dr Zmood’s solution was the genesis of bluechiip, a very small mechanical chip that can register changes in temperature as well as provide a unique ID when scanned.

Today, Bluechiip (ASX:BCT) makes the chips for use in biosample tracking and storage.

“The chip incorporates 52 mechanical beams,” Bluechiip CEO Andrew McLellan said in an interview with Stockhead.

“The best way to think about them is tuning forks – almost like a miniature piano.”

“When you hit the beams with an RF signal, you get a response. If the beam is there, you get a response of ‘one’. If it’s not, you get a ‘zero’. From that you can build millions of different combinations.”

The beams shift slightly with temperature and report back when scanned. Because the chip is mechanical rather than electronic it can also operate in cryogenic storage and withstand sterilisation.

“Every single chip is unique and we can sense temperature. Those are the core benefits,” said Mr McLellan.

“Applications with liquid nitrogen is very much a market that we’re chasing, where items are stored or transported in very low temperatures around -80C or lower. Some of the things stored and transported in those conditions are blood samples, serums, DNA, seeds and different plant materials.”

Mr McLellan said “several hundred thousand” bluechiips had been created so far, for use in IVF labs and biorepositories that store biological samples such as blood and serums.

Flying fowl on the tarmac

However the original problem the chip was designed to solve is far more mundane. It has less to do with human samples, and more to do with chickens.

“The genesis of it goes back to someone who approached me while I was still at RMIT,” said Dr Zmood.

“They had a problem with shipping frozen goods around the country. They were shipping them by air freight. They had an example where the frozen goods had rested on the tarmac and then been refrozen later on. They were effectively spoiled, but no-one knew.

“We call that the ‘frozen chicken problem’.”

Dr Zmood was working at RMIT when he heard about it, but it wasn’t until several years later – while he was a visiting professor at Tel Aviv University in Israel – that he came up with a potential fix.

“The solution I had was to use a little vibrating structure, and then I realised that we could have a multitude of these little vibrating strings and we could use those to store information,” he said.

“When I came back to Australia in 2004, that was when we started working on it seriously. That was when I started the company that was the forerunner to Bluechiip, Mems-ID.”

Bluechiip listed on the ASX in 2011 through an IPO. In 2014 the company’s CEO Brett Schwarz resigned, to be replaced by Mr McLellan.

In April, the company signed a deal with lab equipment maker Labcon North America to buy, use, sell and promote its chips, software and chip readers.

Bluechiip shares have traded between 2c and 4c over the past 12 months. The company spent $439,000 in the June quarter, leaving $1 million in cash, and in July raised another $3.45 million through a rights issue and placement. It expects to spend $1.3 million this quarter.

Dr Zmood said it had taken about 10 years to get bluechiip from idea to reality, and the journey to commercialisation had been longer than he planned. However seeing the chips in action in labs was extremely satisfying.

“I’m pretty happy with it, I just wish the shares were worth a bit more. It looks like with Andrew (McLellan) at the helm, it’s headed in the right direction,” he said.

This article does not constitute financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any financial decisions.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.