Cheap, clean, endless energy: could nuclear fusion reactors be on the grid by 2040?

Tech

Tech

Like green hydrogen, nuclear fusion could provide vast amounts of clean energy and zero emissions from a near inexhaustible fuel source.

Forget coal, gas or nuclear fission – fusion could completely upend our global energy system, if we can get it to work at scale.

Fusion is a star’s energy source. Every second, our Sun turns 600 million tonnes of hydrogen into helium, releasing an enormous amount of energy.

That’s the kind of power scientists are trying to harness.

Countries like the UK, the US and China want to get these “artificial suns” on the grid within three decades.

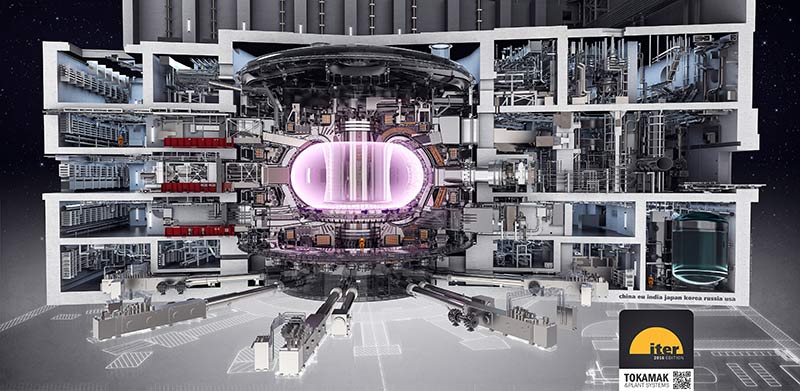

Eyewatering amounts of money are being thrown at research each year. The largest nuclear fusion reaction under development is the +$22 billion ITER tokamak experiment in France, which is scheduled to be turned on for the first time in December 2025.

It looks like this:

All this research means important advances are being made.

Last week, one of China’s nuclear fusion reactors (it has six) reportedly set a new world record for the longest duration of time in sustaining the “sun-like” temperature needed for fusion to occur.

The device held plasma at a temperature of 120 million degrees Celsius for 101 seconds, and at the even hotter temperature of 160 million degrees Celsius for another 20 seconds.

This smashed a December 2020 record held by the Korean Superconducting Tokamak Advanced Research (KSTAR) superconducting fusion device, which held plasma at 100 million degrees Celsius for 20 seconds.

This is a big step forward. Researcher Gong Xianzu calls fusion “a future technology that’s critical for China’s green development push”.

Meanwhile in the UK, scientists have solved one of the major hurdles in developing nuclear fusion energy: excess heat.

Without an exhaust system to handle the intense heat, materials will have to be regularly replaced, significantly affecting the amount of time a power plant could operate for, researchers say.

But a recent experiment suggests the new system, known as a Super-X divertor, would allow components in commercial reactors to last much longer.

This could be a game-changer for creating fusion power plants that deliver affordable, efficient electricity.

“Super-X reduces the heat on the exhaust system from a blowtorch level down to more like you’d find in a car engine,” Dr Andrew Kirk says.

“This could mean it would only have to be replaced once during the lifetime of a power plant.

Kirk said Super-X was a pivotal development for the UK’s plan to put a nuclear fusion power plant on the grid by the early 2040s, and for “bringing low-carbon energy from fusion to the world”.