White Cliff Minerals – a quest to unlock Canadian critical mineral potential

- White Cliff Minerals is about to begin the first exploration program at the Coppermine project in Canada’s Nunavut province in decades

- Alongside that fieldwork, new targets have been identified at Great Bear Lake, 240km away in Canada’s Northwest Territories

- Planned activities include diamond drilling, as well as an initial rock chip and channel sampling program across a wider, regional area of the 2900km2 tenure

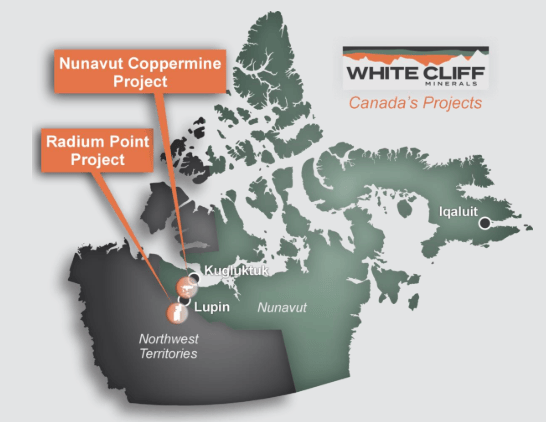

White Cliff Minerals is eyeing a potential treasure trove of gold and critical minerals on the back of prospective and historical exploration results in Canada’s Nunavut province and Northwest Territories.

Nunavut, renowned for being one of the coldest places in Canada, is the country’s largest territory, stretching across most of the Canadian Arctic and occupying about 21% of its land mass.

It also stands as Canada’s newest province, following the signing of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement in 1993 and a consequential six-year transitional period for the establishment of a new territory in 1999.

Yet despite its age, mining companies have been attracted to the under-explored region well before the opening of the North Rankin nickel mine in 1951 – the first large-scale Arctic mining project in the area.

White Cliff Minerals’ search for copper, silver, uranium and gold

One of them is White Cliff Minerals (ASX:WCN), an Australian explorer on the hunt for a smörgåsbord of the minerals we need to reach our clean energy aspirations.

Leveraging advancements in airborne sensing and data gathering technologies, WCN is tapping into Nunavut’s barren, rocky and treeless landscape to follow up on previously identified occurrences of copper and silver at the Coppermine project.

The company managed to secure a swathe of ground following an agreement with a private party for 61 mineral claims covering 805km2 in November last year.

After spending time validating a significant database of historical mineral resources and high-grade outcrop samples, WCN is now fully permitted to begin field activities on what will be the first exploration program at the project in decades.

Great projects with great people

Troy Whittaker, an executive with more than 20 years of experience spanning stints with major global mining companies including Fortescue (ASX:FMG) and Anglo American, took up the role of MD in February, just as WCN began transitioning towards a sharper focus on its Canadian portfolio.

Sitting down with Stockhead, he says the Coppermine project was one of the reasons why he was drawn to work at the company.

“The project is in a fairly tasty part of the world, an area that has returned grades of 20-30% copper in rock chips and hasn’t been looked at for a long, long time,” Whittaker says.

“The second piece is, you want to work on great projects with great people and if you look at the board of WCN, it is made of up of people that have been there and done it.

“I’ve worked with Rod McIllree, our executive chairman before as well as our non-executive director Dan Smith,” he says.

“Rod has experience leading major companies and large-scale projects inside the Arctic circle for over 20 years and when you’re looking for where the next job is, you look for a project that has all the foundations as well as all the excitement just like Coppermine.”

Blue sky estimates a priority at Coppermine

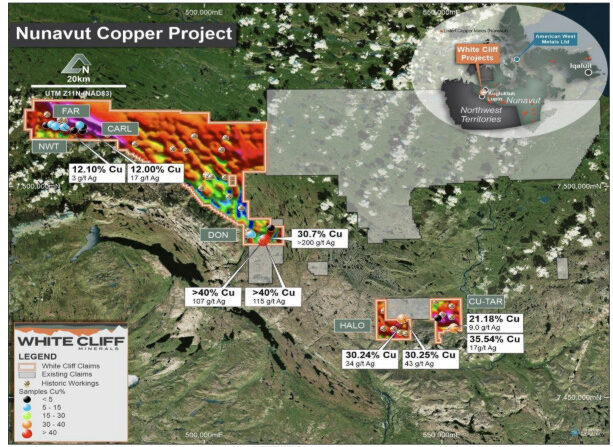

Rich in exploration history, the Coppermine area hosts a raft of high-grade copper lodes that sit along a structural trend consisting of native copper, chalcocite, bornite, and chalcopyrite.

A four-pound copper nugget was discovered by prospector Samuel Hearne in 1771 and by late 1967, more than 40,000 claims were lodged by 70 different companies.

Exploration started to slow by the 1970s due to the instability of the price of copper at the time.

Using existing high-resolution magnetics, as well as extensive rock chip, trend and drill results, the company has now traced outcropping structure and mineralisation over 15km of strike length.

The company’s exploration team is deploying to the field to take up where state, public and private-sponsored historical exploration left off.

The Coppermine project contains numerous non-JORC or NI 43-101 and ‘blue sky’ mineral estimates, which will be a priority during the 2024 field season.

Great Bear Lake

Alongside fieldwork at Coppermine, WCN will also be conducting a review of historic rock chip results at the Great Bear Lake project 240km away in Canada’s Northwest Territories.

Planned activities include diamond drilling, as well as an initial rock chip and channel sampling program across a wider, regional area of the 2900km2 tenure.

In essence, Whittaker says WCN’s team of geologists will be looking to validate the work that has been carried out to date to get a clearer picture of scalability.

“Some of the data that we’ve got shows rock chips up to 14.15% uranium oxide, 6.22g/t gold and 122g/t silver in certain areas but there hasn’t been any expansion on those results,” he says.

“We’ll be looking along strike, concentrating on whether we can turn a 20 to 30m target into something that exceeds >200m.”

Pipeline of targets

The Great Bear Lake licences host several historical mining operations, such as the Eldorado, Echo Bay and Contact Lake mines which produced 13.7Mlb uranium over the course of five decades.

The region last produced uranium via the Eldorado and Echo Bay mines in 1960 but continued to churn out significant quantities of silver and copper until 1982 when all processing activities ceased.

Although exploration at Great Bear Lake has been largely non-existent since the late 1980s, the project sits on the ‘Great Bear magmatic zone’ (GBZ), which contains highly prospective iron-oxide-copper-gold and uranium mineralisation.

It’s regarded by historic miners, explorers and the Northwest Territories Geosciences Office as having the highest potential for IOCG and uranium mineralisation in Canada with pre-1982 production including 13.7Mlbs U3O8, 34.2Moz refined silver and 11.37Mlbs of copper with gold, lead, nickel and cobalt credits.

“Even though it hasn’t been mined since the 1980s, there was exploratory work ongoing by operators which shows extensions to all the mineralisation identified previously,” Whittaker says.

“What we found was operators would go up into the Territories maybe for a season or so, look at something, get really high grades, carry out a capital raise and move on.

“All this work was done in different parts of the project but we’ve gone and consolidated the project, so we’ve got all the pieces of the puzzle now,” he says.

“We’re beginning to put these deposits together and starting to map these strikes which go for over 15km.”

District scale opportunities

Data analysis – focused on revealing prospective and overlooked target regions within the project area – has been ongoing since licences were received in February, but White Cliff believes upcoming works will generate a pipeline of drill targets across a host of prospects.

These prospects include the priority Thomsons prospect, where historical trench sampling by the Geological Survey of Canada returned the 14.15% uranium sample, the Hunter Bay Extension (immediately along strike from a historic estimate of 100,000t at 8.4% copper at the Sloan deposit), Sparkplug Lake, and Spud Bay.

“We’ve got the funding to carry out these activities which puts us in a better place than lot of other explorers,” Whittacker says.

“The historical results are there, and we expect over the next two to three months, it’ll be really exciting because once we validate those results – it is no longer history.

“The work becomes current, and as we look to extend our long strikes, we could well end up with two district scale assets.”

At Stockhead we tell it like it is. While White Cliff Minerals are a Stockhead advertiser, it did not sponsor this article.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.