We’ll need a monster cobalt mine every two years from 2025-26 or we’ll… um, run out

Picture: Getty Images

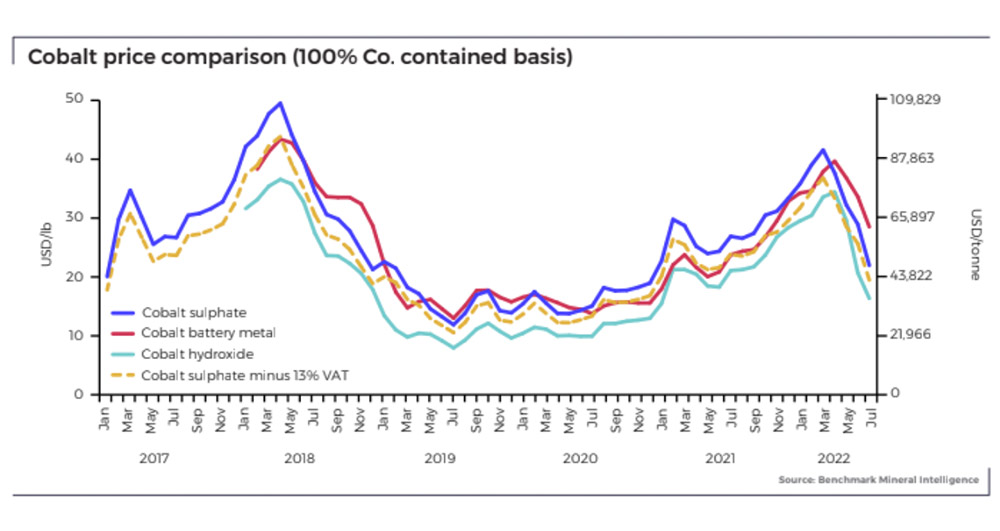

Unlike fellow battery metals lithium and graphite, cobalt has crashed back to earth over the past month and a half.

Cobalt sulphate and hydroxide prices recorded massive losses of 24.4% and 21.4% m-o-m respectively in July, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

But that’s nothing to worry about if you’re a cobalt investor.

As with any small but growing metal market like cobalt – only ~140,000t of metal eq is produced per year – pretty big price fluctuations can happen.

There is a really a combination of two things happening right now to cause the price to move lower.

Firstly China, the main buyer of cobalt, is still in lockdown mode.

Secondly, production from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) – which supplies +66% of the world’s cobalt — has caught up to any short-term deficits in the market.

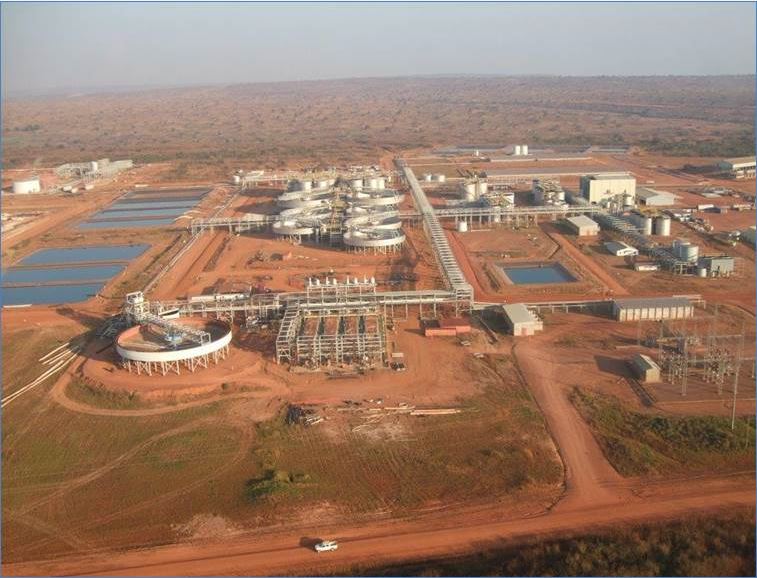

Some big mine restarts, like Glencore’s massive Mutanda copper-cobalt mine, are starting now to kick in.

Following a 145,000t deficit in 2021, the global market will be more balanced in 2022 and 2023 as supply additions keep pace with demand growth, according to the Cobalt Institute’s latest report.

But that’s as balanced as things are going to get for a while.

From 2024, the market is forecast to shift back into a deficit.

This deficit will keep getting bigger into the medium term as supply growth fails to keep pace with demand, the Institute says.

“From 2024-26, supply growth will average 8% per year, compared to more than 12% for demand,” it says.

“Prices will remain elevated to incentivise further investment and prevent wide deficits developing.

“Supply side investment remains critical to ensure sufficient supply into the longer term as cobalt demand continues to rise even higher.”

Perfect timing for ASX project developers like Cobalt Blue (ASX:COB), whose Broken Hill cobalt project (BHCP) is one of the only large scale, non-African, greenfield primary cobalt projects in the world.

The 81,000t BHCP could be in production by mid to late 2025.

It would produce +3,500tpa cobalt metal eq over 20 years at a very low all-in sustaining cost of $US12/lb – making it profitable even at record low prices.

A demonstration plant is now up and running to deliver large scale samples to potential offtake partners.

Project approvals and a BFS will be finalised by the end of the year, ready for a final investment decision on the project by Q1 2023.

We need an ‘elephant’ cobalt mine every two years

But let’s back up a bit.

As per the Cobalt Institute’s report, 12% demand growth from 140,000t is 16,800t of extra cobalt metal a year, every year.

COB is working on a more conservative 8,000 to 9,000tpa – which is still massive.

“That’s ~3 of our projects, to give you a yardstick measure,” COB CEO Joe Kaderavek told Stockhead.

“The two biggest cobalt mines in the world are about 20,000t of cobalt, so you can see we need an elephant mine every two years.

“The demand growth is material.”

Automakers are already planning for cobalt demand surge

Kaderavek says buyers are already looking ahead, prepping for the impending crunch.

“Look at all the brownfields’ expansions, and the return to operation options [in the DRC]. You put them in a plausible trajectory to come back into market and there will only just be enough supply in the next couple of years,” he says.

“Beyond that, the demand keeps going but the supply just isn’t there from the DRC.”

“Those procurement teams are operating on an assumption there will be a significant deficit in the market by 2025-2026.

“We are already seeing a rush for Indonesian cobalt, for example, because the market understands that even if you turn all DRC production on you only get two years of respite and then the market will tighten, once again.”

But the last thing ASX cobalt players want is high prices

It’s true.

During the last cobalt boom in 2017-2018 prices were pushed above $US50/lb, prompting panicked OEMs and automakers to attempt to thrift cobalt from EVs.

If cobalt ramps to a high enough price that it becomes punitive to use, EV makers could be incentivised once again to find non-cobalt technologies.

“That’s my fear,” Kaderavek says.

“My fear is it ramps irrationally, and then innovation being what it is, puts huge pressure on us on the downside.

“An automotive producer might just say ‘that’s it, for the particular vehicle, we are moving away from nickel-cobalt, we are going straight for LFP’.”

Major car makers such as Tesla, Ford and German giant Volkswagen have already announced their adoption of lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) chemistry batteries within their fleet of EVs.

Tesla, for example, announced last month that it will adopt LFPs for its high volume, standard range Model 3 and Model Y electric vehicles.

Want that EV ute? You’ll probably need cobalt in your battery

LFPs are cheaper than NCA (nickel cobalt aluminium) or NCM (nickel cobalt manganese) cells, mainly because they don’t require scarce and price-volatile metals such as nickel or cobalt.

But Kaderavek says the idea that LFPs will somehow cause cobalt demand to stagnate is a fallacy.

Why? Most batteries which remove cobalt, like LFP, have decreased power pack performance, charge slower, and have a poorer range.

“The assumption we are operating under is that 20-25% of all EVs will consistently have no cobalt in them,” he says.

“These are the urban vehicles, which can go from ChargePoint to ChargePoint.

“But for the mass market Western consumer their choice is quite simple – ‘give me a similar utility to a petrol vehicle’.

“’Give me a quick charge, 600-700km range. I do not want to suffer any pain transitioning out of petrol into electric,’ is what the consumer is saying.”

The cobalt market will find a happy medium of around $US27/lb, Kaderavek says, which has been the long-term price for a while.

“At that number it doesn’t create any pricing issues in terms of materials costs for an automotive build,” he says.

“It creates enough of a pricing incentive for new projects like ours, to come online.

“It’s that happy medium. Spot will sometimes miss the happy medium up or down, but long term that the number we look at.

“High enough to incentive new projects, but not too high to create demand destruction.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.