Unless new supplies are found soon, carmakers may start engineering rare earths out of EVs

Pic: Bloomberg Creative / Bloomberg Creative Photos via Getty Images

Volatile pricing and supply risk could force EV manufacturers to consider alternative technologies that don’t rely on rare earth magnets.

Neodymium and praseodymium (NdPr) are used in high-strength permanent magnets, an important part of hybrid and electric vehicle (EV) traction motors.

Each EV also contains about 100 grams of dysprosium.

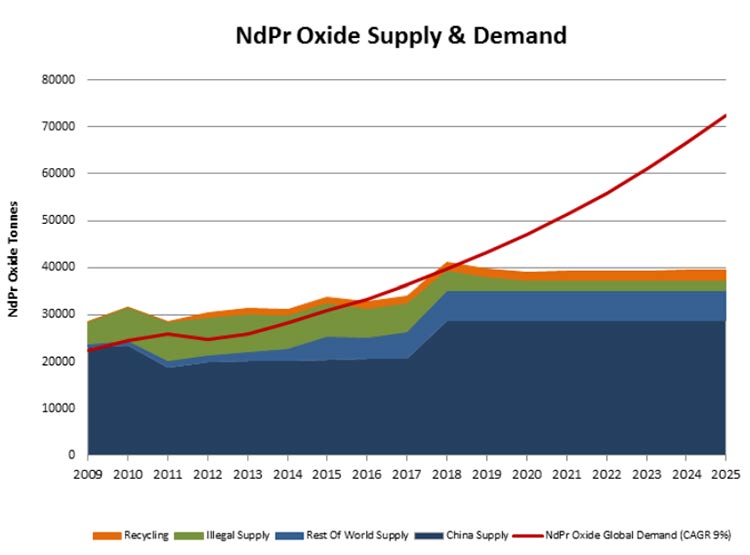

With consumption of rare earths in the EV sector forecast to grow by 4 to 5 per cent a year over the next decade, questions remain over the ability to meet the industry’s rapidly increasing demands.

Magnet producers could start replace the rare earths used in electric vehicles (EV) altogether unless new supply comes online soon.

Roskill analysts say rare earth magnets are not expected to be designed out of the vast majority of HEV/EV motors because of their superior performance and efficiency — but there are alternatives.

“Although NdFeB magnets offer the highest efficiency and best performance for their size and weight, alternatives — specifically induction motors — offer the potential for better long-term price stability,” they say.

“Tesla was unafraid to use induction motors in its Model X and standard Model 3 designs but has switched to a NdFeB permanent magnet motor for its new Model 3 Long Range vehicle.

“Although such substitutions can be made in response to changes in raw material costs, it is worth remembering that drive train development takes many years and is unlikely to be changed once established for a particular model.

“Automotive companies must guard against short-term price rises from early on in a vehicle’s design.”

Earlier this year, Adamas Intelligence said that China’s ongoing government-led crackdown on illegal rare earth mining has led to a 34 per cent drop in global dysprosium production since 2013.

The market researcher believes that China’s production – 86 per cent of the total market — will be insufficient to support global demand growth.

The forecast is that by 2025, China’s demand for dysprosium oxide for EV traction motors alone will amount to 70 per cent of its current “legal” production.

“Rare earth production at operations outside China is forecast to increase significantly in the years to 2028, as existing producers expand production capacity and numerous projects in Australia, Russia, the Americas and Africa are scheduled to be commissioned,” Roskill says.

” The increase in non-Chinese production is expected to significantly reduce China’s stranglehold on REE supply, though China is expected to remain the major supplier of REE products to the global market.”

ASX-listed explorers and miners with producing or advanced rare projects include:

- Alkane Resources (ASX:ALK)

- Arafura Resources (ASX:ARU),

- Lynas Corporation (ASX:LYC),

- Northern Minerals (ASX:NTU)

- Pensana (ASX:PM8); and

- Greenland Minerals (ASX:GGG).

High prices could force substitution

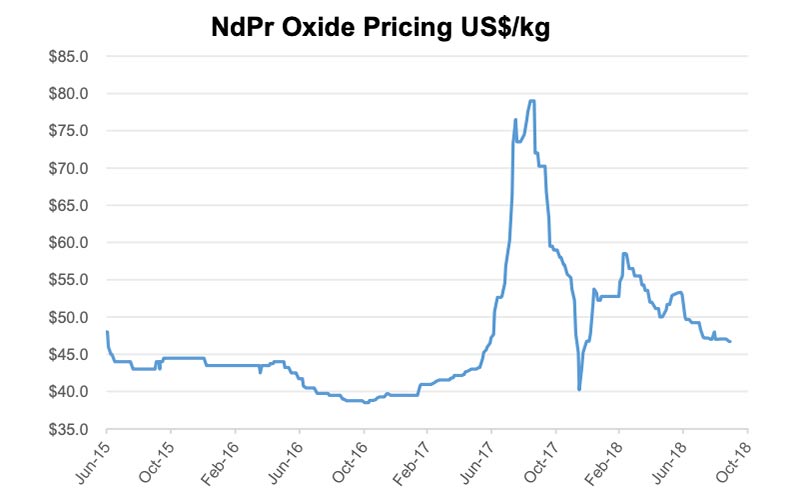

Rare earths producer Lynas Corp told investors that the Chinese NdPr price flattened to an average of $US40.5/kg during the last quarter.

But prices have swung widely over the last few years and are expected to surge again unless new supply comes online.

Delegates at the recent 15th International Rare Earths Conference in Hong Kong agreed that the “pinch point” would come when neodymium prices hit $US100/kg to $US110/kg, Roskill says.

And one speaker said technology first developed in Japan to reduce dysprosium was now used commercially by a number of Chinese companies, while “several” delegates also spoke about substituting dysprosium with fellow rare earth terbium in NdFeB magnets.

Magnet recycling is also increasing, and now accounts for at least 25 per cent of global NdFeB magnet output.

- Subscribe to our daily newsletter

- Bookmark this link for small cap news

- Join our small cap Facebook group

- Follow us on Facebook or Twitter

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.