This junior tin explorer reckons its projects could help bridge the looming supply shortfall

Pic: Schroptschop / E+ via Getty Images

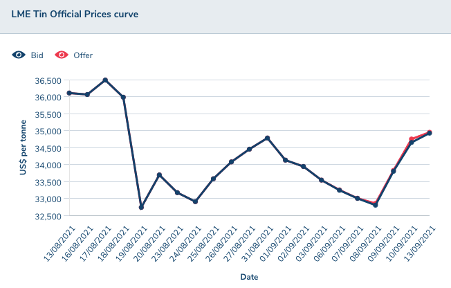

Last month tin prices on the London Metal Exchange (LME) hit historic highs of US$36,000/tonne – compared to US$15,000/tonne at the start of the pandemic.

Today the LME price is sitting at US$33,5000, but inventories are at an all-time low.

Some experts suggest there’s as little as 2.5 days of tin supply sitting in major commodity exchange warehouses in London and Shanghai.

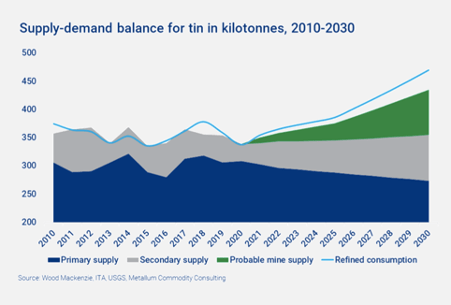

And demand is forecast to outstrip supply by the end of the decade.

This is driven by increased use of electronics, the rise of the Internet of Things and the green energy revolution – which will in turn be driven heavily by electronic technology.

But in the near-term there could be some interesting price movement as Indonesia, a major producer of the world’s tin, enters monsoon season.

Deficit of 30-40,000 tonnes by 2025

CEO of tin junior Elementos (ASX:ELT) Joe David said that tin recovered from the impacts of COVID off the back of substantial purchases of electronics.

“The main use of tin is in electrical solder, the glue that holds together the motherboards and the printed circuit boards and everything that has anything with a decision making/smart component to automation,” he said.

The International Tin Association (ITA) is forecasting a minimum of 30,000-40,000 tonnes deficit into 2025.

“They don’t quote any numbers post 2025, but it’s fair to say the deficit from all their modelling looks like it increases past that quite substantially,” David said.

“That 30,000-40,000 deficit is based on using the historic demand growth factor of 1.8%.

“But in all likelihood, they propose it’s probably going to be closer to 3-4% growth with all the green infrastructure and the move towards electrification.”

The move to hard rock mining a factor

David said the move from alluvial (mining stream bed deposits) to hard rock tin mining is also a factor impacting the industry.

“Data from the ITA appears to point to major producers Indonesia and China as moving into a phase where their supply is dropping off to some extent,” he said.

“With PT Timah in Indonesia, 95% of their resources are now offshore and then they have to do offshore dredging – and deal with all the environmental challenges that come with that.

“The alluvial deposits around the world have been been mined, so a lot of the industry is moving into hard rock tin mining but most of the easy stuff has been mined out already.

“And most of the deposits around the world are underground – which obviously leads to high costs to develop, and higher costs to mine.

“So, there’s a bit of a structural change that’s happened in the industry.”

Favourable economics to push towards production

The company’s working on the definitive feasibility study (DFS) for its Oropesa tin project in Spain and reckons the by-product of the deficit is going to be a solid tin price.

“We did an updated economic study at the start of 2020 which was pretty favourable with decent returns – but that was based on a $19,750 tin price,” David said.

“Today, it’s over US$33,000 on the LME so the economics of the project look fantastic right now.

“We believe the by-product of the deficit is going to be a supportive tin price because all the forecasts we’re seeing show it staying over US$30,000/tonne for another couple of years.

“We’re keen to get this project up and running as quick as possible, but we’ll need all of next year to complete the DFS, and then a couple of years after that, to get it constructed and into operation.”

Along with the DFS, the company is aiming to release an updated mineral resource estimate for the project in October.

The project is also an open pit mine which the company said would be low cost to bring into production compared to an underground mine.

Established Tasmanian project a bonus

In addition to its Spanish project, Elementos holds the Cleveland brownfields project in Tasmania which has about 7.5 million tonnes of resource at about 0.75% tin and 0.3% copper.

It’s an established underground mine – which means capital expenditure will be much lower than peers who would have to establish declines from scratch.

“It’s a decent looking resource, and the decline is fully established,” David said.

“And there’s some very good-looking mineralisation that wasn’t mined when they were targeting high grades back in the day.

“So, we’re hoping to hit some additional mineralisation and then that becomes a very clear, parallel development story for the company.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.