The secret recipe that could make Impact Minerals HPA’s Michelin Star chef

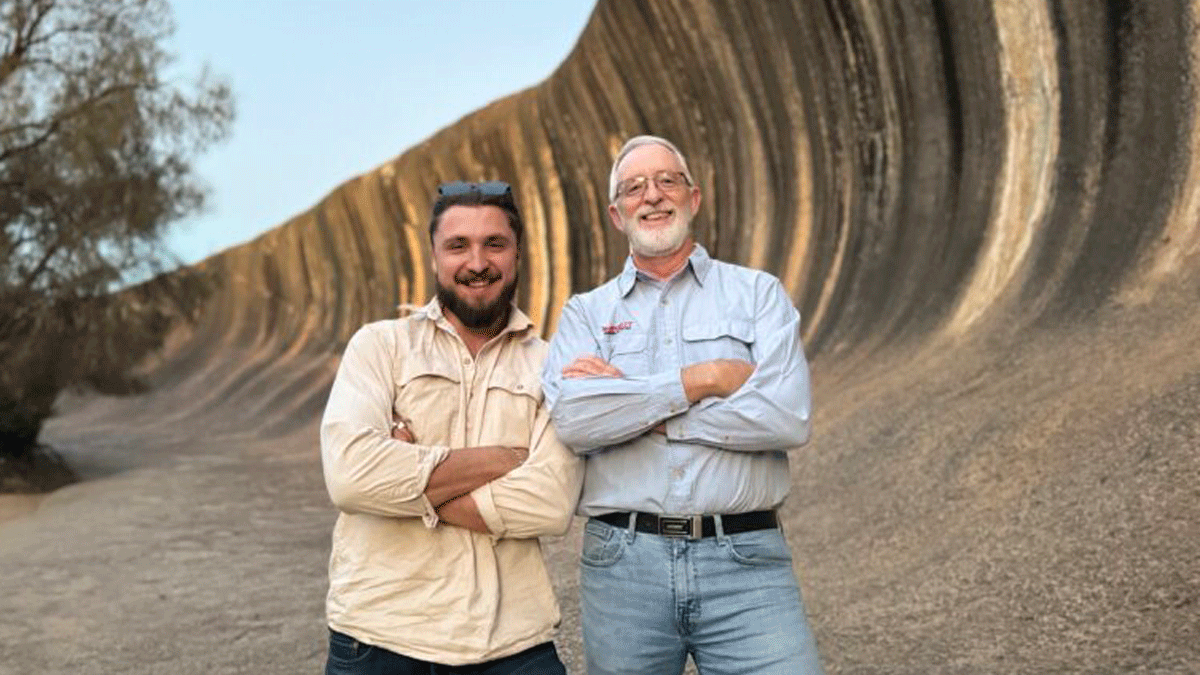

Impact MD Mike Jones (right). Picture: Josh Chiat

- Impact Minerals is aiming to become a disruptive player in the high purity alumina market

- Boss Dr Mike Jones thinks the company could produce the critical material cheaper than any producer or developer currently in the supply chain

- The key is a novel process developed in a literal kitchen and a salt lake containing 80 years of feedstock just 2m from surface

Like all good recipes, Roland Gotthard’s new processes for producing high purity alumina began in the kitchen.

Specifically his home in Perth, where experiments showing sulphuric acid could reduce a clay into the critical mineral were posted to LinkedIn two years ago.

A second process using secret reagents — kept close to Gotthard’s chest amid a patent application — was completed at close to ambient temperatures of around 90 degrees Celsius.

The refinery? His family’s slow cooker. Normally tasked with brewing delicious casseroles, the ceramic pot was stuffed by the end.

But not before the geologist-cum-not-so-mad scientist produced alumina salt with a purity of 99.8%.

“The literature says this should leach at 90 degrees, it’s not boiling, it’s corrosive of chemicals, obviously, but wear a couple rubber gloves and some eyeglasses and I could do it at home,” Gotthard said.

“So I just got the slow cooker out of the kitchen, my wife’s like, ‘what the hell are you doing?’ I filtered it all off, did some reactions and created the 99.8% purity salt in my own kitchen.”

Bench scale test work by pro lab ALS has since demonstrated the efficacy of both methods to produce 99.99% — or 4N — high purity alumina.

Trading at prices of ~US$20,000/t, it’s a key component in the nickel-rich lithium ion batteries used in high-end Tesla EVs and the sapphire glass in LED lights.

Gotthard’s LinkedIn jaunts caught the eye of Impact Minerals (ASX:IPT) and its managing director Dr Mike Jones, no stranger to innovation having entered the Australian mining industry with Western Mining Corporation’s famous exploration division in the 1980s.

Impact, which had been working with BHP(ASX:BHP) and its Xplor incubator program to target copper near the famous Broken Hill silver, lead and zinc mine, leapt at the opportunity.

The deal will see Impact develop a new process to produce HPA it thinks can be significantly cheaper and cleaner than current and prospective producers.

Geology is key

Key to the pivot was the acquisition of Lake Hope, two salt lakes around 100km east of Hyden on the border of WA’s Goldfields and Wheatbelt regions.

By completing a pre-feasibility study — expected to be done by the end of this year — Impact can up its stake via an earn-in agreement to 80%.

Playa One, controlled by Gotthard and a collection of family and friend investors, would hold the remaining 20%.

Lake Hope was identified by Gotthard and Co. a few years ago using open source geophysical data.

Most HPA is effectively reverse engineered, produced by Japanese conglomerate Sumitomo and a collection of Chinese processors from already refined aluminium metal.

This places Australian hopefuls in the unusual position of disruptors.

Australia has long been a major player in fields like nickel, lithium and even alumina, but is facing pressure from cheaper suppliers in Asia utilising new technology.

ASX HPA players want to flip that narrative, leveraging Australia’s industrial and geological knowledge to produce the critical mineral more efficiently.

Orica-backed Alpha HPA (ASX:A4N) is up 750% since 2019 — now capped at ~$950 million — planning to use industrial waste in North Queensland as a feedstock.

Cadoux (ASX:CCM) want to produce it from a high-grade kaolin deposit, but are in recovery mode after the former FYI Resources was dumped by its proposed JV partner Alcoa early last year.

Both Cadoux and A4N plan to use hydrometallurgical processes distinct from the sulphate and low temperature leach processes tested by Gotthard and used to produce 99.99% HPA at bench scale by ALS.

A scoping study Impact tabled in December last year suggested the company could produce HPA at sector low operating costs of just US$3264/t, generating 10,000tpa with annual post-tax cash flows of $174m a year.

Underpinning that is Lake Hope, which contains 3.5Mt of mud-like ore just 2m deep, enough to be mined for 80 years on Impact’s early assessments.

At a grade of 25.1%, that’s 880,000t of alumina, or Al2O3.

If a PFS and 10t pilot plant this year is successful and mining approvals are straight-forward, Impact could be producing demonstration plant rates of 1000-2000tpa in a couple of years.

“It’s really the natural advantages that the geology has given us in this lake,” Jones said.

“We can see that (mining) it is going to be relatively straightforward. And so the estimated cost of production that we have now is significantly below any other producer globally.

“Across the whole mining and technology sector we’re being disrupted on a daily basis by new materials, new ideas, in particular in the battery space.

“And so it is a race to get to production and keep those costs as low as possible. But we (could be) so significantly lower than anybody else that we think we’ve got a big head start and should be able to get to production before any other disruption comes along.”

The shallow nature of the deposit — formed from the deposition of rainwater over millions of years — means drilling is extremely cost effective, much of it done by Gotthard and fellow geo Martin Neumann with only a PVC pipe and rubber hammer.

Lake Hope’s quirkiness is such the head falling off one of the mallets was described internally as a ‘rig failure’ … easily fixed with a trip to the hardware shop in the agricultural hub of Hyden.

It means Impact’s ~$2m cash pile will go a long way before a raising to support the pilot plant and PFS is needed later this year.

The Hemi of HPA?

At a market cap of just $39 million, Impact is a minnow relative to other HPA stocks.

And, with its own in-house geology team, it has been running the ruler over a number of other projects in rare earths and base metals in recent years.

They include the Arkun REE project, currently being drilled, and Broken Hill in NSW, a large early stage exploration project that seems to be the best proposition for a spin-out or JV.

But none have yet come up with the sort of scale a single-operation company would require to re-rate.

Jones thinks Lake Hope, along with a planned processing plant likely in Kwinana’s ‘Battery Alley’ or the coal turned ‘future tech’ hub of Collie, could be that project.

“I’m on record as saying, if you’re going to build a one mine small gold project — or copper or even lead — it is a waste of everyone’s time,” Jones said.

“You need to be working on a world class deposit in order to really create long term shareholder wealth. And if we look at discoveries like the Chalice (ASX:CHN) discovery, initially, recently Azure (ASX:AZS) and a few years ago De Grey (ASX:DEG) they’re all billion dollar market cap companies just during the exploration phase.

“And that’s the scale that we set Impact up to find.

“We’ve found a few small things, we’ve been a bit unlucky over the years in terms of several small, very interesting deposits but they never grew to a size that warranted development.

“So when we came across this project it was like, OK we haven’t discovered it ourselves — we discovered it on LinkedIn as we’ve spoken about — (but) it’s a 50 year mine life at least, that’s one tick for world class.

“It’s got very low operating costs — second tick. And the third tick is a growing market with high margins so we can’t not give it a go.”

Batteries and LEDs

In a study conducted for Alpha HPA in 2022, CRU Group projected supply deficits in the HPA market would emerge by 2026.

Jones says prospective offtakers are already asking Impact for material to test and qualify once it becomes available.

It has already made inroads with alumina buyers in Europe and America, who are concerned about the concentration of the supply chain in China.

That means so-called ‘reputable supply’, the proportion which would be IRA compliant in America and compliant with similar regulations in the EU, is around half of 2030 demand — something CRU projects will lift beyond 120,000tpa.

“We have a report that CRU did in back in 2018-19 and these figures have actually proven to be quite accurate over the last four or five years,” Jones said.

“So the market is expanding at about 20% per annum.”

Much of that growth has come from EV batteries, where is separates the anode and cathode to prevent overheating and ‘thermal runaway’.

AKA This.

JUST IN: Fire crews are currently on the scene of a battery fire at Moorabool, near Geelong. Firefighters are working to contain the fire and stop it spreading to the nearby batteries. https://t.co/5zYfOfohG3 #7NEWS pic.twitter.com/HAkFY27JgQ

— 7NEWS Melbourne (@7NewsMelbourne) July 30, 2021

There is around 5kg of HPA in every electric vehicle — if that vehicle uses a nickel-cobalt-manganese or nickel-cobalt-aluminium cathode chemistry.

But lithium-ferro-phosphate or LFP batteries, which are cheaper (though less energy dense), safer and don’t contain HPA, are grabbing increased market share, especially in the dominant Chinese EV market.

HPA’s role in LED demand, which Gotthard says is growing around 15% a year, provides insurance against changes in battery technology.

“So we’re looking more not necessarily (just) feeding into batteries, but feeding into LEDs and that demand is just steadily growing,” he said.

Riding the Wave

Located down a fire break that doubles as an access road to the remote ‘magic lake’, if they can get the mine up and running Impact would be one of a handful of operators in a sparsely explored district.

The closest town Hyden is a largely farming community which has experience as a service centre for projects like the Bounty gold mine and Forrestania nickel mines.

Bought by IGO (ASX:IGO) in its disastrous acquisition of Western Areas, Forrestania is about to be put on ice as its Flying Fox and Spotted Quoll mines wrap up and nickel prices remain under water.

In that context, Impact could emerge as an important contributor to a region famed for Katter Kich, a Ballardong Nyungar cultural site more commonly known as Wave Rock.

To be clear, no one has any intentions to mine that site, which also doubles as the catchment for the town’s water supply.

But Jones believes the town can become a base for the project, which would likely be mined on a campaign rather than continual basis — akin to Lynas Rare Earths’ (ASX:LYC) Mt Weld mine.

Over to the east are the traditional owners of Lake Hope, the Ngadju People, experienced in mining having struck a landmark native title agreement with IGO and its Nova nickel mine east of Norseman over a decade ago.

A heritage survey has already been carried out, identifying no sites of cultural significance and just one artefact outside the boundaries of the lake itself.

Jones is confident of navigating negotiations with the Ngadju Aboriginal Corporation and the prospect of drawing support from Federal and State Governments like the Critical Minerals Facility once it comes to funding the ~$250m project.

“I think there’s a very good chance of that. We applied last year, I think it was the second year that they’d run the critical minerals grant at the federal level,” he said.

“They gave a significant amount of funding ($4.6m) to Andrew Forrest and IGO to (plan) a process plant for downstream (nickel) processing in Kwinana — in Battery Alley.

“We only wanted a measly $1.5m funding, which we didn’t get, but those things come up annually and then there are also other funds that we can apply for which are perhaps a little bit more appropriate. We will certainly be putting applications in for those.

“There’s obviously politics involved in any grant of that scale and that nature, and it is putting jobs and money back into the economy.

“So in principle I don’t object (to larger companies receiving support) but I think that the funds should be spread more widely to smaller groups like ourselves.

“We’re trying to innovate and that’s where the breakthroughs are made and so we’ll see how we go in the next round.”

Impact Minerals (ASX:IPT) share price today

The reporter travelled to Lake Hope as a guest of Impact Minerals.

At Stockhead, we tell it like it is. While Impact Minerals was a Stockhead advertiser at the time of writing, it did not sponsor this article.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.