The Explorers: Force’s Jason Brewer on that 2400g/t silver hit at Tshimapala

Pic: Bloomberg Creative / Bloomberg Creative Photos via Getty Images

The silver and lead grades at Force Commodities’ (ASX:4CE) recently acquired Tshimpala project in Malawi are truly ridiculous.

In 2018, assays on a 100-tonne bulk sample returned 60 per cent lead and 765 grams per tonne (g/t) silver.

Then last week, Force reported 2411g/t silver and 60 per cent lead from a grab sample which looks like this:

It’s basically metal.

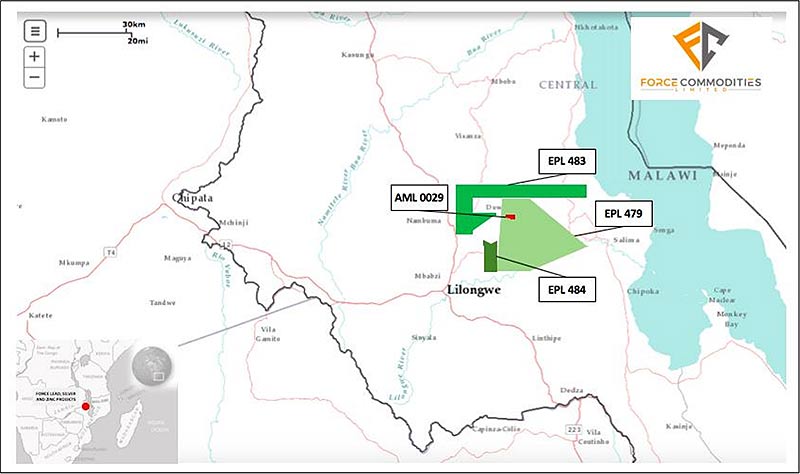

When Force signed a deal to buy the 1400sqkm Tshimpala base metals project in May, the silver price languished around $US14/oz ($20/oz). Now its closing in on $US20/oz.

Great timing for shareholders, because Force is moving quickly to establish an intial small volume — but high margin — direct shipping operation (DSO) operation.

How quick? The company has already signed offtake and transport deals, is undertaking mining studies, and will have mobile crushing equipment on site very soon.

Once Force is making money from this near-surface stuff, it wants to unlock the prospectivity of the wider project through exploration.

Where is this high-grade lead/silver coming from? Force managing director Jason Brewer wants to find out.

What is Malawi like for an explorer?

“It’s one of the poorest countries in the world, but the infrastructure is fantastic.

You can see the government has invested in public infrastructure, like roads and rail. Having worked in the DRC for the last three years, to go to Malawi and see this infrastructure is incredible.

The quality of the infrastructure here can not be questioned. Obvious benefits for $4CE @Force_ASX as it looks to advance its activities here. Roads like this have a huge impact on local trade and in attracting investment. pic.twitter.com/ekOibX7MUb

— Jason Brewer (@JBrewerMining) August 18, 2019

It is located near Tanzania, Mozambique, and Zambia – countries which are known for their tremendous mineral resources.

Even so, agriculture accounts for about 90 per cent of Malawi’s GDP, so the focus hasn’t traditionally been on mining.

There are resources companies in Malawi; it just hasn’t received the same attention as its neighbours.

Paladin spent several hundred million dollars to get the Kayelekera uranium mine into production, but then put it on care and maintenance after a couple of years.

Now, Hylea Metals (ASX:HCO) has done a deal to buy it, which is fantastic.

You have AIM listed Mokango Resources developing a rare earths project, as well as Sovereign Metals (ASX:SVM) focused on graphite and rutile.

Malawi is a place where you can do business. They want to diversify the economy; they want their natural resources to be developed in the right way.”

Are Force’s DRC lithium projects on the backburner now?

“The appetite for DRC-based junior resources has come off, there is no doubt about that, and lithium has gone the same way.

I think shareholders would kill me if we invested money there in the current market.

When you have the most established producers struggling – what joy is there for a junior exploration company operating in the DRC? It’s hard enough for companies operating here in WA.

We still have those joint ventures and we will continue maintain them, but right now we a fully focused on Tshimpala.”

How did you find Tshimpala in the first place?

“There are some massive, world-class resources in Africa. But they also come with world class problems, and it’s very difficult to fund development as a junior resources company right now.

So, we started identifying high margin, low capex projects which we could get into production very quickly.

Through various contacts we were shown this advanced graphite project in Malawi.

I met with one of the geologists that had worked on it several years before, and he mentioned that in addition to the graphite there was artisanal miners working this high-grade lead-silver mineralisation.

Then we went out there to see Tshimpala — I’m used to working on mining projects where you mine ore, but these artisanals were effectively mining metal. That’s how high grade it is.

We met some very good local partners and they assisted us to get the transaction done quickly.”

You guys are moving very quickly.

“We announced the heads of agreement in May and concluded the deal in July.

We have an offtake agreement with [global commodities group] Transamine, and we have signed a transport and logistics agreement with Bolloré, Africa’s biggest logistics transportation group.

Prices are linked to the prevailing prices for lead and silver. We get 80 per cent of that paid at port, and then the balance when it gets delivered in China under the offtake agreement.

If this is grading 60 per cent lead, 2000g/t silver – you can work out the inherent value here.

We have the RC rig up there at the end of this month to punch 150 shallow holes, focussed on establishing a mineable resource.

We just said ‘right … what do we need to do to give us the confidence to make the next level of investment?’ That is what this RC program will achieve.

It’s a 2500m RC program — 150 holes between 15 and 25m deep, on a 15m by 50m grid spacing.

We also announced last week that we had agreed to purchase some mobile crushing equipment in country:

It is high quality Metso gear, and operating hours are between 500 and 800 so the engines have barely been warmed up.

They will be delivered to site, fully recommissioned. We are acquiring them under a capital lease arrangement – monthly payments from operations, and then within 12 months they are ours.

We will be appointing a mining contractor shortly. They are going to work with our guys to basically finalise the mining volumes for that initial mining program. It’s moving ahead very quickly.

It’s only going to take one or two shipments before the initial capital is be paid back. That will give us the ability to fund a broader exploration program.”

How did you sort the offtake without concrete volumes or a resource?

“The offtake is for 100 per cent of production. They have seen some of the initial larger assay work [100 tonne samples] done on this project, and the guys from Transamin have worked in Malawi so they know of the project.

Transamin have also taken small volumes out of Malawi so they know the nature of this material.

Typically, they would get a silver-lead concentrate delivered to then which is high in moisture content.

This is metal — it has moisture content of zero. Transamin also likes Tshimpala because there is very little (if any) zinc content, which means they don’t have the issue of separating the zinc from the lead.

This is, in their minds, a premium product. They will take as much as we can produce.

We still have to give them some indication of volumes over the coming months. We will have more confidence in production volumes over the first half of October.

Then Transamin will give us a clear delivery schedule which we will need to adhere to.”

Does the fact that you found that 2400g/t, 60 per cent lead grab sample speak to the prospectivity of the wider area?

“That grab sample was found 2km south and along strike from the Grand Canyon prospect [on the mining lease].

And there’s another 25-odd artisanal working areas; again, we are just scraping the surface here.

There is a lot of this mineralisation in the wider area. We have mapped something like 25 small artisanal areas near the area we have initially focused on.

We have identified over 5km of these mineralised veins already, just in a tiny area.”

So this project represents short term cashflow – but then you have the longer term exploration upside?

“Absolutely. Our initial target is to be a small volume, high margin producer.

We want to generate early cashflow and use that to identify the source of this mineralisation and expand the resource base. Where is this high-grade lead-silver coming from?”

Will this low-cost approach to project development become more popular among juniors?

“Previously, you would have companies come to Africa searching for the world’s biggest deposit – with the view that if you got it big enough you would be bought out by a Rio Tinto, a Vale, or a big Chinese company.

But that model of juniors coming in and finding a world class deposit – and there are many in Africa, we all know that – then being brought out at a massive premium are now gone.

The Chinese are smarter, and the major miners have been bitten.

For example, [ASX listed] Africa Iron, which had an iron ore project in the DRC, was sold to [JSE listed] Exxaro for $300m.

Exxaro then sold that project a couple of years ago for $2m.

Look what happened with Rio’s acquisition of the [Mozambique-based coal developer] Riversdale – they eventually wrote that off, all $3.2 billion dollars’ worth.

So, as juniors, we have to adapt to the market and recognise our own constraints. Where is the capital coming from? How much do we need?

Every company has visions of grandeur, but what can we realistically achieve? My view is that if you come into a project with the view of getting it as big as possible to sell it on – forget it.”

Did you believe silver was due to rebound when you bought Tshimpala – or is it so high-grade that it didn’t even matter?

When we started looking at Tshimpala, silver was at between $US14 and $US15/oz. But seeing where gold was going, there was always the expectation that silver would follow at some point.

From announcing the heads of agreement to now, I think that basket price of lead and silver has gone up 25 to 30 per cent. That all goes to the top line.

It’s a great benefit to us, but we were comfortable going into the project on previous prices.

It’s shallow, the grades are just ridiculous, now it’s up to us to demonstrate that we can build a sound development plan — and then deliver.”

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.