Something stinks about this Elon Musk battery metals tweet. Let’s place it under the microscope.

Pic: Scott Olson/Getty Images

- Elon Musk, owner of Twitter and boss of Tesla, says copper won’t need additional supply to service the energy transition and lithium just needs more refining capacity

- Experts clap back

- Lithium legend Ken Brinsden says high prices show how difficult it is to develop a lithium mine

Even before he went ahead and bought the platform, professional ‘smart guy’ Elon Musk was no stranger to getting in trouble with his Twitter account.

He’s currently going through the courts for a controversial tweet from almost five years ago about taking EV maker Tesla private, something that never happened.

No amount of criticism could stop Musk, briefly the world’s richest man, from doing just about anything, and he’s continued to operate his digital megaphone with reckless abandon to this day.

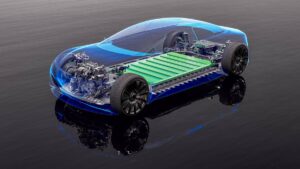

Given Tesla is a big buyer of battery metals to make its globetrotting supply of electric vehicles, every now and then he sleepwalks into out favourite corner of the Twitterverse, the mining fintwit community.

This time he’s got tongues wagging for a comment that verges on the absurd.

Read it and weep.

No change in copper production is required for the transition to sustainable energy.

Lithium refinement needs to increase dramatically, but lithium ore itself is extremely common throughout Earth.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) January 22, 2023

Suffice to say Musk’s views have a whiff of flippancy about them and run contrary to the prevailing opinion of virtually any expert in the mining and commodity industry.

And they’re already drawing criticism.

Interesting that @elonmusk has done more to create #lithium demand via @Tesla & more to limit lithium supply than anyone on the planet by continuing to make foolish comments about how abundant lithium is in the earth’s crust – discouraging investment. First principles??? https://t.co/1sy7POcSA4

— Joe Lowry (@globallithium) January 23, 2023

Is lithium rare? Proof is in the pudding

Is the bottleneck actually in lithium refining?

Ken Brinsden, the chair of Canadian explorer Patriot Battery Metals (ASX:PMT) and formerly the managing director of all time industry success story Pilbara Minerals (ASX:PLS), says it’s a complete misreading of the situation.

While lithium may be a common metal in terms of its endowment on Earth, the quantity we have the technology to mine or extract economically makes it much rarer.

“What makes a good lithium raw material project relatively rare is the combination of grade, location and then a broader sort of piece around recoverability,” he said.

“The most obvious sort of ploy is to say, ‘well, there’s lithium in seawater’, and of course there is, there’s lots of it. But it’s impossible to recover cost effectively.”

That’s reflected in recent prices, which have seen spodumene producers selling lithium concentrate containing just 6% of the metal or less at between US$5000-8000/t on the spot market, and chemical prices which rose over 130% last year to a tick over US$80,000/t.

“There’s no point in having refining capacity if you don’t have the raw materials and it feels like they are imagining you can generate the lithium raw material from thin air and refine it,” Brinsden said.

“Obviously, the industry just doesn’t work like that and if ever you needed evidence to indicate that it’s the raw material that’s in shortage have a look at firstly, the cost of spodumene … and then the other is the cost of the value added products.”

Will Musk’s take tank the battery metals market?

Musk’s notoriety extends well beyond public understanding of the mining investment sector, and his commentary gets plenty of eyes on commodities that could hold sway with retail investors.

Take for instance his bullish stance on lithium back in July, which prompted a small rally for Aussie stocks.

Or his bearish comments on cobalt from back in 2018.

It’s always good to get a sense of where people are coming from when they comment on things like supply and demand.

While miners will always be keen to highlight supply shortages, which generally portend higher prices, customers stuck paying more for raw materials will obviously want to see prices head lower.

The EV price CV:

EV raw materials costs more than doubled to over US$8000 per vehicle during the pandemic, not great for carmakers like Tesla who know there is only so long EVs can rely solely on the luxury market.

Musk has a similar stance to fellow billionaire Andrew Forrest, who told analysts and reporters last year he did not see a shortage in lithium despite commentary to the contrary from industry monitors.

Forrest was being quizzed about whether the iron ore miner’s green energy arm Fortescue Future Industries was concerned about rising costs in battery raw materials as it looks to decarbonise its mine sites.

Value-added lithium prices in China have fallen around 15% early this year on sluggish demand ahead of Lunar New Year, but prices for spodumene and South American brine-derived lithium carbonate are still strong.

Pilbara Minerals is set to deliver its first dividend in FY23 after raking in over $850 million in the December quarter, selling close to 150,000t of 5.4% Li2O spodumene at an average price of US$5668/dmt.

Its long term peer Allkem (ASX:AKE) highlighted the struggle to bring on even conventional new spodumene operations after finally securing environmental approval for its James Bay deposit in Canada after almost five years last week.

Its marketing chief Christian Cortes says demand will be constrained by supply until at least 2030.

But Musk is, if nothing else, an influencer. And his comments hold sway when it comes to sentiment.

So far it’s done little to shake the lithium market. Miners surged yesterday, with Pilbara up 6.15%, IGO (ASX:IGO) lifting 3.06% and Mineral Resources (ASX:MIN) up 2.01%.

Allkem (ASX:AKE) gained 4.22%, while Core Lithium (ASX:CXO) rose 5.69%.

“He’s great on technology, and the predictive model about where industry is headed, except for the fact that he doesn’t understand raw material supply and that’s the key issue,” Brinsden said.

“There’s a reasonable chance that it might impact sentiment for a short period of time, but the facts speak for themselves and the facts are unfortunately for Elon something completely different.

“Raw material is in short supply, that’s why it’s going to cost a lot more into the future to access it. Honestly, that’s a fact. I don’t think that you’re really going to be able to avoid it, as much as Elon might like to think otherwise.”

Copper for the transition? We’ll need a lot of it

So what about copper?

According to the International Energy Agency, the often quoted source for this kind of thing, we’ll actually need more copper for the energy transition.

A whole lot more. It says the expansion of electricity grids to handle renewable energy will see copper demand for power lines alone double by 2040.

“In a scenario consistent with climate goals, expected supply from existing mines and projects under construction is estimated to meet only half of projected lithium and cobalt requirements and 80% of copper needs by 2030,” the IEA says.

Industry analysts are similarly concerned about copper supply.

Canaccord Genuity thinks total copper demand could grow by 40% by 2030.

“We expect copper demand from traditional market segments (i.e. excluding new energy technologies) to grow by ~8% to 26.7Mt by 2026, with stronger supply growth through 2023-25 calling for modest market surpluses,” Canaccord said in a note last November.

“However, to illustrate long-term demand growth potential, our indicative modelling of demand from new energy technologies suggests overall refined copper consumption could grow 41% to 38Mt by 2030.

“This compares with third-party forecasts such as S&P Global at 40Mt (50Mt by 2035), and the IEA at ~35Mt by 2040 under a “Sustainable Development Scenario”.”

Goldman Sachs thinks we’ll need 8Mt of additional copper production by 2030. It’s a number that doesn’t sound so high until you consider that would mean 8 replicas of BHP and Rio Tinto’s Escondida mine, the world’s largest.

By contrast, the International Copper Study Group says refined copper production through the first 11 months of 2022 increased around 3.4% to 23.483Mt, about 83% of capacity, with the market in a 384,000t deficit.

There are clouds hanging over dominant producers Chile and Peru, where protests from local communities, drought and Covid 19 infections have constrained output.

The world’s most prolific copper jurisdiction Chile has seen production down 8% on pre-Covid levels, with Peru up a spare 3% on 2021 levels after stoppages at the Cuajone and Las Bambas mines and a political crisis.

Bloomberg estimates 2% of world copper production has been taken off the board during shutdowns linked to political unrest at MMG’s Las Bambas and Glencore’s Antapaccay mine.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.