School of Rock: What are All In Sustaining Costs and what do they mean for gold miners?

Picture: John W. Banagan/Stone Collection via Getty Images.

Back in 2012 the gold price rose to what were at the time record levels above US$1600/oz, something which seemed at the time to spell bumper returns for gold investors.

Imagine the confusion when Canadian behemoth Barrick’s earnings were US$538 million in the red despite its reported $463/oz ‘cash costs’ suggesting the company could have been making US$1206 on each of the 7.4Moz it produced.

Other majors were little better and the blowback from investors prompted the world’s biggest gold miners and the World Gold Council to do something about it, rolling out the now ubiquitous All In Sustaining Cost (AISC) reporting method in 2013.

“Prior to that there were things companies were reporting like a cash cost, or a total cash cost, or they might have been a C1 or a C2 and some of the companies had their own measurements as well, which were unique,” says Sam Ulrich, an expert on AISC who reports Australia’s quarterly average costs via his firm Aurum Analytics.

“So there was no sort of real way to compare between companies very easily. And the other thing was this large disconnect that was being seen between cash costs, and any sort of form of profit, or some companies were then reporting losses so obviously investors were upset.

“It was mainly sort of the larger companies which sort of got together with the World Gold Council to put together the framework for the all in sustaining costs and the all in cost.”

The shift proved so successful AISC reporting has now been extended far and wide across the mining industry, particularly into base metals.

But what is actually recorded in all in sustaining costs, what can it tell you about a company or operation, and is it even a true reflection of what a gold company is spending to keep their mines running?

Devil in the detail?

So what is AISC and how does it compare to the other reporting measures?

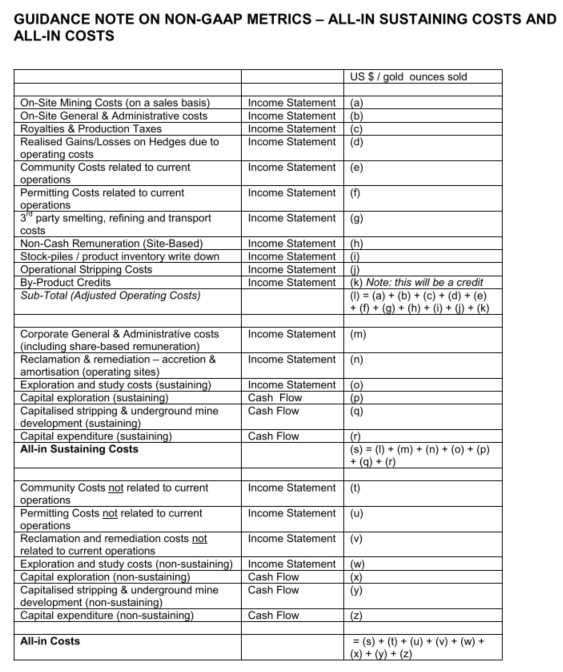

Ulrich says it is in effect all of the things mining companies pay to keep an operation running at steady state.

“So the big thing is the AISC probably doesn’t include capital costs for expansions or things like that,” he told Stockhead.

“So essentially, you’ve got your mining costs, your processing costs, there’s royalties in there, community costs related to the current operation.

“Whether there’s refining and transport costs, which is probably more of an effect for maybe ones which are sort of gold, copper, or something like that. Adjustments for stockpiles, by product credits, if there’s a large amount of copper, or maybe it might be a high-grade silver as well.

“And then there’s the general on site administration costs, whether there’s any reclamation and remediation costs going on in there, exploration which sustains the operation.”

That sounds pretty exhaustive, but as gold miners regularly claimed during the WA gold royalty debate in 2017, it does not give a complete sense of the costs of managing an operation and a company’s profit margin.

There is another step above called all in costs which also includes things like development costs which have a material impact on the bottom line.

“There’s things which are probably not in there, which which relates to what’s called the next level up, the All in Costs,” Ulrich said.

“Which are things which are not related specifically to that operation, but might be happening in that area around the mine.

“There might be remediation not related to the current operations … capital, exploration costs, which don’t need to sustain the minesite, and capital expenditure, which isn’t to sustain the current operation in the form that it’s in.”

So how do AISC relate to margins?

Clearly AISC does not always relate directly to margins, but Ulrich said it is the best metric we’ve seen, and certainly far easier for investors to track than the multiple different methods employed by mining companies before the AISC became standardised.

“The best of the bad bunch that we’ve had in the past from cash costs, total cash costs, which was probably the basis for where the all in sustaining cost came from, because that disconnect was so large between, ‘hey, we’re producing at a cash cost of $600 an ounce, and so the gold price at that time was $1,000 per ounce,” Ulrich said.

“And people go ‘OK maybe they’re making a profit of $400 per ounce’, and then they’re making a loss and people are going, ‘what’s going on?’ So this is closer to reality.

“I don’t know if you could make it absolutely capture everything because obviously there’s lots of obviously non-cash things which go into financials – depreciation, amortisation and things like that, which change the actual cash profitability.

“There is a disconnect, and this one is probably is a lot closer to reality than past measures have been.”

Ulrich says all in cost is closer, but that a smaller percentage of companies regularly report it.

Analysts can often work out an all in cost from financial measures provided in half year and annual reports, but for Australian companies they only have to provide that data twice a year – TSX-listed companies need to provide these figures every three months.

“The All in Cost, which a smaller percentage of the companies report with their all in sustaining costs, is probably closer, if you took that minus the gold price, or what they’ve realised as their gold price,” Ulrich said.

“Not everyone is actually getting the spot gold price, because of hedging. They could be getting more or for many presently they might be getting less because they got forward sales a few years ago, and then the gold price went way up above those forward prices.”

Ulrich said Evolution Mining (ASX:EVN) was one company that regularly reported and promoted its all in costs.

Costs are rising, but not as fast as prices

Evolution boss Jake Klein, an advocate for fiscal conservatism in the gold sector, has queried the rising costs being seen across the sector, telling Stockhead last month there were a number of operations that would be vulnerable to a US$300/oz fall in the gold price.

A few years ago efficient Australian companies were the toast of the global gold sector for their record low costs as they turned to profitability as they recovered from the 2013 collapse in the gold price.

But as gold prices have climbed from around US$1550/oz a few years ago to current levels of US$1816/oz ($2485/oz), all in sustaining costs have risen as well.

According to figures from Aurum Analytics, average AISC reported at Australian gold operations have risen 30% from four year lows of $1099/oz in the first quarter of 2018 to $1433/oz in the June quarter of 2021, having touched $1453/oz in the March quarter.

On a weighted basis that comes in at $1237/oz, but that is skewed by the fact Australia’s biggest gold mine, Newcrest’s (ASX:NCM) Cadia, is producing at negative costs because it counts revenue from its copper by-product against its production costs.

The gold price over the same time has increased by 39%, providing more leeway for companies to loosen their belts as well.

Ulrich said miners have been incentivised to mine lower grade material as the price has risen, increasing their cost base.

“Obviously what happens with a rise in the gold price, it allows many companies to reassess the gold price that they put into their ore reserves,” he said. “So raising that can actually allow them to mine lower grade gold.”

Worldwide, costs rose by 5% in the March Quarter to US$1048/oz, the highest level since the June Quarter of 2013 (the quarter which saw the last major gold price collapse). Despite a 14% drop in operating margins the World Gold Council said they remained healthy, with just the 4% highest operating cost mines running at an AISC above the gold price.

Can your gold mine survive a downturn? Check the reserve model

Ulrich said declining average gold grades – which separate research shows could fall as much as 44% from 2019 levels by 2029 – appeared to be the main driver of higher costs, although he said labour pressures, particularly behind WA’s border fortress, may be increasing as well.

The type of operation can also have an impact. Though not a hard and fast rule, open pit gold mines tend to have the lowest costs. Mixed open pit and underground operations are typically the highest cost. Purely underground mines are somewhere in the middle.

If you wanted to know which companies could quickly adjust their operations to survive a drop in the gold price, Ulrich said it was important to look at their ore reserve models.

“Some companies are very sheltered because they have a very conservative gold price in their ore reserve models,” he said. “And that is something that Evolution actually promotes that they’re conservative in that respect.

“If you look at the large players, Newmont is very conservative, so they wouldn’t need to change their operations, it would have to be quite a severe downward trend on the gold price.

“Whereas other companies you might see the gold price used in their ore reserves has also increased sort of in line, so they might have less buffer to work with.

“And then, obviously, you’ve got to change an entire potential mine plan, which obviously you can do computer wise very quickly, but then you’ve got to implement it.”

For this reason Ulrich said it was important to look at a gold miner’s reserve model and what gold price they are using to underpin their mine plans.

“I think the big thing is when you look at especially smaller companies, what is the gold price used for their reserves to assess whether it can sustain through the cycle, as opposed to can it just get on and get the gold out during the boom?” he said.

Emissions linked to grades

Did you know gold grades and production costs could be an ESG indicator as well?

One of the areas of research Ulrich has looked at in his PhD studies around AISC is the link between operational costs, mined gold grades and greenhouse gas emissions intensity.

“If you look at greenhouse gas emissions, and you convert it to an intensity as in greenhouse gas emissions per ounce produced, you can actually then compare it to costs and grade,” he said.

“What you generally find is, obviously, underground miners generally have higher grades, so they will have a lower greenhouse gas emissions intensity per ounce compared to an open pit mine just because that’s how it sort of works through grade.

“But what I have found is that there is a very strong relationship when a mine’s in steady state. But it’s not a linear relationship, it’s sort of a curved relationship. And so, if your grade declines, actually the emissions intensity rises quite rapidly.

“If they were focusing on the ones which had lower emissions intensities, obviously, a mine which has a declining grade profile might move out of what they might be looking at.”

It is not completely even however, and operations need to be compared to others within their own class. For instance, while big open pit mines generally have lower costs than underground operations they typically have higher greenhouse gas emissions.

“They sort of need to be sort of treated separately,” Ulrich said.

“Underground mines have around a 40% lower emissions intensity, on average, than open pit mines and the open pit and underground mines were in between.”

“You can sort of sort of say, on average, open pit mines were the lowest cost, but had the highest emissions intensity, the open pit and underground mines had the highest costs and in the middle emissions intensity, and the underground mines were sort of a cost in between the two, but had the lowest emissions intensity.”

In Australia, around 70% of a gold mine’s emissions are caused by power generation, so Ulrich said it was important to look at the mix of renewables, gas, diesel and coal in an operation’s remote power supply or local electricity grid.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.